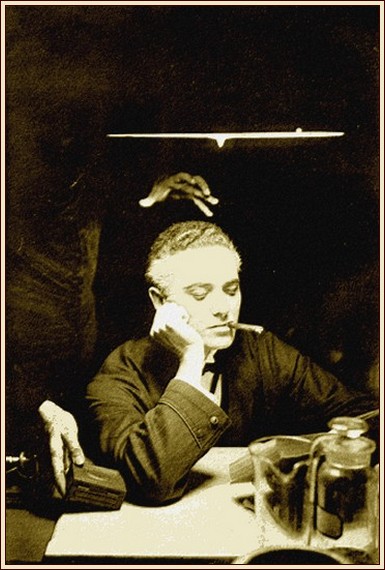

| Sanford Quest | Herbert Rawlinson |

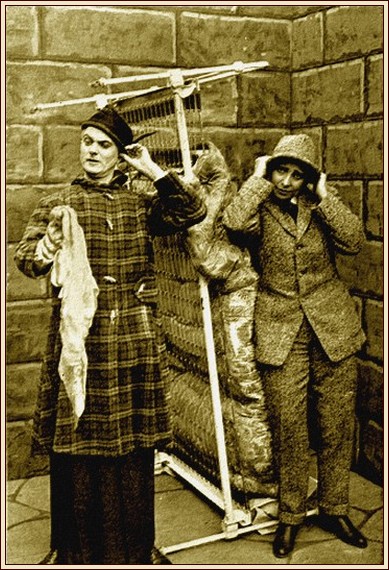

| Lenora MacDougal | Anna Little |

| Prof. Ashleigh Lord Ashleigh |

William Worthington |

| Lady Ashleigh | Helen Wright |

| John Craig | Frank MacQuarrie |

| Laura, Quest’s assistant | Laura Oakley |

| Mrs. Bruce Rheinholdt | Hylda Sloman |

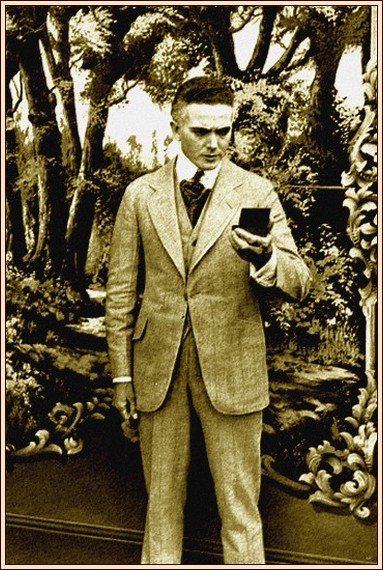

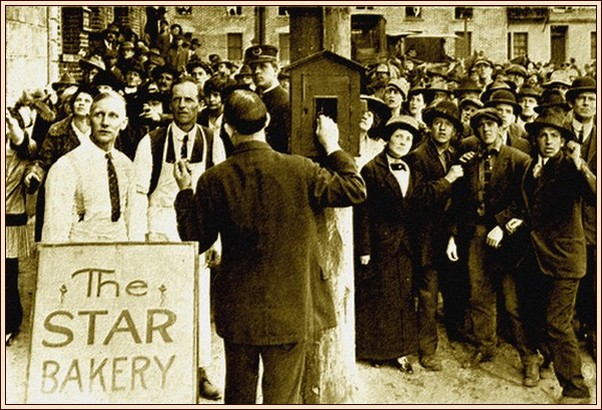

Sanford Quest, Criminologist.

The young man from the west had arrived in New York only that afternoon, and his cousin, town born and bred, had already embarked upon the task of showing him the great city. They occupied a table in a somewhat insignificant corner of one of New York’s most famous roof-garden restaurants. The place was crowded with diners. There were many notabilities to be pointed out. The town young man was very busy.

“See that bunch of girls on the right?” he asked. “They are all from the chorus in the new musical comedy—opens to-morrow. They’ve been rehearsing every day for a month. Some show it’s going to be, too. I don’t know whether I’ll be able to get you a seat, but I’ll try. I’ve had mine for a month. The fair girl who is leaning back, laughing, now, is Elsie Havers. She’s the star…. You see the old fellow with the girl, just in a line behind? That’s Dudley Worth, the multi-millionaire, and at the next table there is Mrs. Atkinson—you remember her divorce case?”

It was all vastly interesting to the young man from the west, and he looked from table to table with ever-increasing interest.

“Say, it’s fine to be here!” he declared. “We have this sort of thing back home, but we are only twelve stories up and there is nothing to look at. Makes you kind of giddy here to look past the people, down at the city.”

The New Yorker glanced almost indifferently at the one sight which to a stranger is perhaps the most impressive in the new world. Twenty-five stories below, the cable cars clanging and clashing their way through the narrowed streets seemed like little fire-flies, children’s toys pulled by an invisible string of fire. Further afield, the flare of the city painted the murky sky. The line of the river scintillated with rising and falling stars. The tall buildings stabbed the blackness, fingers of fire. Here, midway to the clouds, was another world, a world of luxury, of brilliant toilettes, of light laughter, the popping of corks, the joy of living, with everywhere the vague perfume and flavour of femininity.

The young man from the country touched his cousin’s arm suddenly.

“Tell me,” he enquired, “who is the man at a table by himself? The waiters speak to him as though he were a little god. Is he a millionaire, or a judge, or what?”

The New Yorker turned his head. For the first time his own face showed some signs of interest. His voice dropped a little. He himself was impressed.

“You’re in luck, Alfred,” he declared. “That’s the most interesting man in New York—one of the most interesting in the world. That’s Sanford Quest.”

“Who’s he?”

“You haven’t heard of Sanford Quest?”

“Never in my life.”

The young man whose privilege it was to have been born and lived all his days in New York, drank half a glassful of wine and leaned back in his chair. Words, for a few moments, were an impossibility.

“Sanford Quest,” he pronounced at last, “is the greatest master in criminology the world has ever known. He is a magician, a scientist, the Pierpont Morgan of his profession.”

“Say, do you mean that he is a detective?”

The New Yorker steadied himself with an effort. Such ignorance was hard to realise—harder still to deal with.

“Yes,” he said simply, “you could call him that—just in the same way you could call Napoleon a soldier or Lincoln a statesman. He is a detective, if you like to call him that, the master detective of the world. He has a great house in one of the backwater squares of New York, for his office. He has wireless telegraphy, private chemists, a little troop of spies, private telegraph and cable, and agents in every city of the world. If he moves against any gang, they break up. No one can really understand him. Sometimes he seems to be on the side of the law, sometimes on the side of the criminal. He takes just what cases he pleases, and a million dollars wouldn’t tempt him to touch one he doesn’t care about. Watch him go out. They say that you can almost tell the lives of the people he passes, from the way they look at him. There isn’t a crook here or in the street who doesn’t know that if Sanford Quest chose, his career would be ended.”

The country cousin was impressed at last. With staring eyes and opened mouth, he watched the man who had been sitting only a few tables away from them push back the plate on which lay his bill and rise to his feet. One of the chief maîtres d’hôtel handed him his straw hat and cane, two waiters stood behind his chair, the manager hurried forward to see that the way was clear for him. Yet there was nothing about the appearance of the man himself which seemed to suggest his demanding any of these things. He was of little over medium height, broad-shouldered, but with a body somewhat loosely built. He wore quiet grey clothes with a black tie, a pearl pin, and a neat coloured shirt. His complexion was a little pale, his features well-defined, his eyes dark and penetrating but hidden underneath rather bushy eyebrows. His deportment was quite unassuming, and he left the place as though entirely ignorant of the impression he created. The little cluster of chorus girls looked at him almost with awe. Only one of them ventured to laugh into his face as though anxious to attract his notice. Another dropped her veil significantly as he drew near. The millionaire seemed to become a smaller man as he glanced over his shoulder. The lady who had been recently divorced bent over her plate. A group of noisy young fellows talking together about a Stock Exchange deal, suddenly ceased their clamour of voices as he passed. A man sitting alone, with a drawn face, deliberately concealed himself behind a newspaper, and an aldermanic-looking gentleman who was entertaining a fluffy-haired young lady from a well-known typewriting office, looked for a moment like an errant school-boy. Not one of these people did Sanford Quest seem to see. He passed out to the elevator, tipped the man who sycophantly took him the whole of the way down without a stop, walked through the crowded hall of the hotel and entered a closed motor-car without having exchanged greetings with a soul. Yet there was scarcely a person there who could feel absolutely sure that he had not been noticed.

* * * * *

Sanford Quest descended, about ten minutes later, before a large and gloomy-looking house in Georgia Square. The neighbourhood was, in its way, unique. The roar and hubbub of the city broke like a restless sea only a block or so away. On every side, this square of dark, silent houses seemed to be assailed by the clamour of the encroaching city. For some reason or other, however, it remained a little oasis of old-fashioned buildings, residences, most of them, of a generation passed away. Sanford Quest entered the house with a latch-key. He glanced into two of the rooms on the ground-floor, in which telegraph and telephone operators sat at their instruments. Then, by means of a small elevator, he ascended to the top story and, using another key, entered a large apartment wrapped in gloom until, as he crossed the threshold, he touched the switches of the electric lights. One realised then that this was a man of taste. The furniture and appointments of the room were of dark oak. The panelled walls were hung with a few choice engravings. There were books and papers about, a piano in the corner. A door at the further end led into what seemed to be a sleeping-apartment. Quest drew up an easy-chair to the wide-flung window, touching a bell as he crossed the room. In a few moments the door was opened and closed noiselessly. A young woman entered with a little bundle of papers in her hand.

“Anything for me, Laura?” he asked.

“I don’t believe you will think so, Mr. Quest,” she answered calmly.

She drew a small table and a reading lamp to his side and stood quietly waiting. Her eyes followed Quest’s as he glanced through the letters, her expression matched his. She was tall, dark, good-looking in a massive way, with a splendid, almost unfeminine strength in her firm, shapely mouth and brilliant eyes. Her manner was a little brusque but her voice pleasant. She was one of those who had learnt the art of silence.

The criminologist glanced through the papers quickly and sorted them into two little heaps.

“Send these,” he directed, “to the police-station. There is nothing in them which calls for outside intervention. They are all matters which had better take their normal course. To the others simply reply that the matter they refer to does not interest me. No further enquiries?”

“Nothing, Mr. Quest.”

She left the room almost noiselessly. Quest took down a volume from the swinging book-case by his side, and drew the reading lamp a little closer to his right shoulder. Before he opened the volume, however, he looked for a few moments steadfastly out across the sea of roofs, the network of telephone and telegraph wires, to where the lights of Broadway seemed to eat their way into the sky. Around him, the night life of the great city spread itself out in waves of gilded vice and black and sordid crime. Its many voices fell upon deaf ears. Until long past midnight, he sat engrossed in a scientific volume.

“This habit of becoming late for breakfast,” Lady Ashleigh remarked, as she set down the coffee-pot, “is growing upon your father.”

Ella glanced up from a pile of correspondence through which she had been looking a little negligently.

“When he comes,” she said, “I shall tell him what Clyde says in his new play—that unpunctuality for breakfast and overpunctuality for dinner are two of the signs of advancing age.”

“I shouldn’t,” her mother advised. “He hates anything that sounds like an epigram, and I noticed that he avoided any allusion to his birthday last month. Any news, dear?”

“None at all, mother. My correspondence is just the usual sort of rubbish—invitations and gossip. Such a lot of invitations, by-the-bye.”

“At your age,” Lady Ashleigh declared, “that is the sort of correspondence which you should find interesting.”

Ella shook her head. She was a very beautiful young woman, but her expression was a little more serious than her twenty-two years warranted.

“You know I am not like that, mother,” she protested. “I have found one thing in life which interests me more than all this frivolous business of amusing oneself. I shall never be happy—not really happy—until I have settled down to study hard. My music is really the only part of life which absolutely appeals to me.”

Lady Ashleigh sighed.

“It seems so unnecessary,” she murmured. “Since Esther was married you are practically an only daughter, you are quite well off, and there are so many young men who want to marry you.”

Ella laughed gaily.

“That sort of thing may come later on, mother,” she declared,—“I suppose I am only human like the rest of us—but to me the greatest thing in the whole world just now is music, my music. It is a little wonderful, isn’t it, to have a gift, a real gift, and to know it? Oh, why doesn’t Delarey make up his mind and let father know, as he promised!… Here comes daddy, mum. Bother! He’s going to shoot, and I hoped he’d play golf with me.”

Lord Ashleigh, who had stepped through some French windows at the farther end of the terrace, paused for a few minutes to look around him. There was certainly some excuse for his momentary absorption. The morning, although it was late September, was perfectly fine and warm. The cattle in the park which surrounded the house were already gathered under the trees. In the far distance, the stubble fields stretched like patches of gold to ridges of pine-topped hills, and beyond to the distant sea. The breakfast table at which his wife and daughter were seated was arranged on the broad grey stone terrace, and, as he slowly approached, it seemed like an oasis of flowers and fruit and silver. A footman stood discreetly in the background. Half a dozen dogs of various breeds came trotting forward to meet him. His wife, still beautiful notwithstanding her forty-five years, had turned her pleasant face towards him, and Ella, whom a great many Society papers had singled out as being one of the most beautiful débutantes of the season, was welcoming him with her usual lazy but wholly good-humoured smile.

“Daddy, your habits are getting positively disgraceful!” she exclaimed. “Mother and I have nearly finished—and our share of the post-bag is most uninteresting. Please come and sit down, tell us where you are going to shoot, and whether you’ve had any letters this morning?”

Lord Ashleigh loitered for a moment to raise the covers from the dishes upon a side table. Afterwards he seated himself in the chair which the servant was holding for him.

“I am going out for an hour or two with Fitzgerald,” he announced. “Partridges are scarcely worth shooting yet but he has arranged a few drives over the hills. As for my being late—well, that has something to do with you, young lady.”

Ella looked at him with a sudden seriousness in her great eyes.

“Daddy, you’ve heard something!”

Lord Ashleigh pulled a bundle of letters from his pocket.

“I have,” he admitted.

“Quick!” Ella begged. “Tell us all about it? Don’t sit there, dad, looking so stolid. Can’t you see I am dying to hear? Quick, please!”

Her father smiled, glanced for a moment at the plate which had been passed to him from the side table, approved of it and stretched out his hand for his cup.

“I heard this morning,” he said, “from your friend Delarey. He went into the matter very fully. You shall read his letter presently. The sum and substance of it all, however, is that for the first year of your musical training he advises—where do you think?”

“Dresden,” Lady Ashleigh suggested.

“Munich? Paris?” Ella put in breathlessly.

“All wrong,” Lord Ashleigh declared. “New York!”

There was a momentary silence. Ella’s eyes were sparkling. Her mother’s face had fallen.

“New York!” Ella murmured. “There is wonderful music there, and Mr. Delarey knows it so well.”

Lord Ashleigh nodded portentously.

“I have not finished yet. Mr. Delarey wound up his letter by promising to cable me his final decision in the course of a few days. This cablegram,” he went on, drawing a little slip of blue paper from his pocket, “was brought to me this morning whilst I was shaving. I found it a most inconvenient time, as the lather—”

“Oh, bother the lather, father!” Ella exclaimed. “Read the cablegram, or let me.”

Her father smoothed it out before him and read—

TO LORD ASHLEIGH, HAMBLIN HOUSE, DORSET, ENGLAND.

I FIND A MAGNIFICENT PROGRAMME ARRANGED FOR AT METROPOLITAN OPERA HOUSE THIS

YEAR. HAVE TAKEN BOX FOR YOUR DAUGHTER, ENGAGED THE BEST PROFESSOR IN THE

WORLD, AND SECURED AN APARTMENT AT THE LEELAND, OUR MOST SELECT AND

COMFORTABLE RESIDENTIAL HOTEL. UNDERSTAND YOUR BROTHER IS STILL IN SOUTH

AMERICA, RETURNING EARLY SPRING, BUT WILL DO OUR BEST TO MAKE YOUR DAUGHTER'S

YEAR OF STUDY AS PLEASANT AS POSSIBLE. ADVISE HER SAIL ON SATURDAY BY

MAURETANIA.

“On Saturday?” Ella almost screamed.

“New York!” Lady Ashleigh murmured disconsolately. “How impossible, George!”

Her husband handed over the letter and cablegram, which Ella at once pounced upon. He then unfolded the local newspaper and proceeded to make an excellent breakfast. When he had quite finished, he lit a cigarette and rose a little abruptly to his feet as a car glided out of the stable yard and slowly approached the front door.

“I shall now,” he said, “leave you to talk over and discuss this matter for the rest of the day. I believe you said, dear,” he added, turning to his wife, “that we were dining alone to-night?”

“Quite alone, George,” Lady Ashleigh admitted. “We were to have gone to Annerley Castle, but the Duke is laid up somewhere in Scotland.”

“I remember,” her husband assented. “Very well, then, at dinner-time to-night you can tell me your decision, or rather we will discuss it together. James,” he added, turning to the footman, “tell Robert I want my sixteen-bore guns put in the car, and tell him to be very careful about the cartridges.”

He disappeared through the French windows. Lady Ashleigh was studying the letter stretched out before her, her brows a little knitted, her expression distressed. Ella had turned and was looking out westwards across the park, towards the sea. For a moment she dreamed of all the wonderful things that lay on the other side of that silver streak. She saw inside the crowded Opera House. She felt the tense hush, the thrill of excitement. She heard the low sobbing of the violins, she saw the stage-setting, she heard the low notes of music creeping and growing till every pulse in her body thrilled with her one great enthusiasm. When she turned back to the table, her eyes were bright and there was a little flush upon her cheeks.

“You’re not sorry, mother?” she exclaimed.

“Not really, dear,” Lady Ashleigh answered resignedly.

Lord Ashleigh, who in many respects was a typical Englishman of his class, had a constitutional affection for small ceremonies, an affection nurtured by his position as Chairman of the County Magistrates and President of the local Unionist Association. After dinner that evening, a meal which was served in the smaller library, he cleared his throat and filled his glass with wine. His manner, as he addressed his wife and daughter, was almost official.

“I am to take it, I believe,” he began, “that you have finally decided, Ella, to embrace our friend Delarey’s suggestion and to leave us on Saturday for New York?”

“If you please,” Ella murmured, with glowing eyes. “I can’t tell you how grateful I am to you both for letting me go.”

“It is naturally a wrench to us,” Lord Ashleigh confessed, “especially as circumstances which you already know of prevent either your mother or myself from being with you during the first few months of your stay there. You have very many friends in New York, however, and your mother tells me that there will be no difficulty about your chaperonage at the various social functions to which you will, of course, be bidden.”

“I think that will be all right, dad,” Ella ventured.

“You will take your own maid with you, of course,” Lord Ashleigh continued. “Lenora is a good girl and I am sure she will look after you quite well, but I have decided, although it is a somewhat unusual step, to supplement Lenora’s surveillance over your comfort by sending with you, also, as a sort of courier and general attendant—whom do you think? Well, Macdougal.”

Lady Ashleigh looked across the table with knitted brows.

“Macdougal, George? Why, however will you spare him?”

“We can easily,” Lord Ashleigh declared, “find a temporary butler. Macdougal has lived in New York for some years, and you will doubtless find this a great advantage, Ella. I hope that my suggestion pleases you?”

Ella glanced over her shoulder at the two servants who were standing discreetly in the background. Her eyes rested upon the pale, expressionless face of the man who during the last few years had enjoyed her father’s absolute confidence. Like many others of his class, there seemed to be so little upon which to comment in his appearance, so little room for surmise or analysis in his quiet, negative features, his studiously low voice, his unexceptionable deportment. Yet for a moment a queer sense of apprehension troubled her. Was it true, she wondered, that she did not like the man? She banished the thought almost as soon as it was conceived. The very idea was absurd! His manner towards her had always been perfectly respectful. He seemed equally devoid of sex or character. She withdrew her gaze and turned once more towards her father.

“Do you think that you can really spare him, daddy,” she asked, “and that it will be necessary?”

“Not altogether necessary, I dare say,” Lord Ashleigh admitted. “On the other hand, I feel sure that you will find him a comfort, and it would be rather a relief to me to know that there is some one in touch with you all the time in whom I place absolute confidence. I dare say I shall be very glad to see him back again at the end of the year, but that is neither here nor there. Mr. Delarey has sent me the name of some bankers in New York who will honour your cheques for whatever money you may require.”

“You are spoiling me, daddy,” Ella sighed.

Lord Ashleigh smiled. His hand had disappeared into the pocket of his dinner-coat.

“If you think so now,” he remarked, “I do not know what you will say to me presently. What I am doing now, Ella, I am doing with your mother’s sanction, and you must associate her with the gift which I am going to place in your keeping.”

The hand was slowly withdrawn from his pocket. He laid upon the table a very familiar morocco case, stamped with a coronet. Even before he touched the spring and the top flew open, Ella knew what was coming.

“Our diamonds!” she exclaimed. “The Ashleigh diamonds!”

The necklace lay exposed to view, the wonderful stones flashing in the subdued light. Ella gazed at it, speechless.

“In New York,” Lord Ashleigh continued, “it is the custom to wear jewellery in public more, even, than in this country. The family pearls, which I myself should have thought more suitable, went, as you know, to your elder sister upon her marriage. I am not rich enough to invest large sums of money in the purchase of precious stones, yet, on the other hand, your mother and I feel that if you are to wear jewels at all, we should like you to wear something of historic value, jewels which are associated with the history of your own house. Allow me!”

He leaned forward. With long, capable fingers he fastened the necklace around his daughter’s neck. It fell upon her bosom, sparkling, a little circular stream of fire against the background of her smooth, white skin. Ella could scarcely speak. Her fingers caressed the jewels.

“It is our farewell present to you,” Lord Ashleigh declared. “I need not beg you to take care of them. I do not wish to dwell upon their value. Money means, naturally, little to you, and when I tell you that a firm in London offered me sixty thousand pounds for them for an American client, I only mention it so that you may understand that they are likely to be appreciated in the country to which you are going.”

She clasped his hands.

“Father,” she cried, “you are too good to me! It is all too wonderful. I shall be afraid to wear them.”

Lord Ashleigh smiled reassuringly.

“My dear,” he said, “you will be quite safe. I should advise you to keep them, as a rule, in the strong box which you will doubtless find in the hotel to which you are going. But for all ordinary occasions you need feel, I am convinced, no apprehension. You can understand now, I dare say, another reason why I am sending Macdougal with you as well as Lenora.”

Ella, impelled by some curious impulse which she could not quite understand, glanced quickly around to where the man-servant was standing. For once she had caught him unawares. For once she saw something besides the perfect automaton. His eyes, instead of being fixed at the back of his master’s chair, were simply riveted upon the stones. His mouth was a little indrawn. To her there was a curious change in his expression. His cheekbones seemed to have become higher. The pupils of his eyes had narrowed. Even while she looked at him, he moistened a little his dry lips with the tip of his tongue. Then, as though conscious of her observation, all these things vanished. He advanced to the table, respectfully refilled his master’s glass from the decanter of port, and retreated again. Ella withdrew her eyes. A queer little feeling of uneasiness disturbed her for the moment. It passed, however, as in glancing away her attention was once more attracted by the sparkle of the jewels upon her bosom. Lord Ashleigh raised his glass.

“Our love to you, dear,” he said. “Take care of the jewels, but take more care of yourself. Your mother and I will come to New York as soon as we can. In the meantime, don’t forget us amidst the hosts of your new friends and the joy of your new life.”

She gave them each a hand. She stooped first to one side and then to the other, kissing them both tenderly.

“I shall never forget!” she exclaimed, her voice breaking a little. “There could never be any one else in the world like you two—and please may I go to the looking-glass?”

The streets of New York were covered with a thin, powdery snow as the very luxurious car of Mrs. Delarey drew up outside the front of the Leeland Hotel, a little after midnight. Ella leaned over and kissed her hostess.

“Thank you, dear, ever so much for your delightful dinner,” she exclaimed, “and for bringing me home. As for the music, well, I can’t talk about it. I am just going upstairs into my room to sit and think.”

“Don’t sit up too late and spoil your pretty colour, dear,” Mrs. Delarey advised. “Good-bye! Don’t forget I am coming in to lunch with you to-morrow.”

The car rolled off. Ella, a large umbrella held over her head by the door-keeper, stepped up the little strip of drugget which led into the softly-warmed hall of the Leeland. Behind her came her maid, Lenora, and Macdougal, who had been riding on the box with the chauffeur. He paused for a moment to wipe the snow from his clothes as Ella crossed the hall to the lift. Lenora turned towards him. He whispered something in her ear. For a moment she shook. Then she turned away and followed her mistress upstairs.

Arrived in her apartment, Ella threw herself with a little sigh of content into a big easy-chair before the fire. Her sitting-room was the last word in comfort and luxury. A great bowl of pink roses, arrived during her absence, stood on the small table by her side. Lenora had just brought her chocolate and was busy making preparations in the bedroom adjoining. Ella gave herself up for a few moments to reverie. The magic of the music was still in her blood. She had made progress. That very afternoon her master, Van Haydn, had spoken to her of her progress—Van Haydn, who had never flattered a pupil in his life. In a few weeks’ time her mother and father were coming out to her. Meanwhile, she had made hosts of pleasant friends. Attentions of all sorts had been showered upon her. She curled herself up in her chair. It was good to be alive!

A log stirred upon the fire. She leaned forward lazily to replace it and then stopped short. Exactly opposite to her was a door which opened on to a back hall. It was used only by the servants connected with the hotel, and was usually kept locked. Just as she was in the act of leaning forward, Ella became conscious of a curious hallucination. She sat looking at the handle with fascinated eyes. Then she called aloud to Lenora.

“Lenora, come here at once.”

The maid hurried in from the next room. Ella pointed to the door.

“Lenora, look outside. See if any one is on that landing. I fancied that the door opened.”

The maid shook her head incredulously.

“I don’t think so, my lady,” she said. “No one but the waiter and the chambermaid who comes in to clean the apartment, ever comes that way.”

She crossed the room and tried the handle. Then she turned towards her mistress in triumph.

“It is locked, my lady,” she reported.

Ella rose to her feet and herself tried the handle. It was as the maid had reported. She, however, was not altogether reassured. She was a young woman whose nerves were in a thoroughly healthy state, and by no means given to imaginative fears. She stood a little away, looking at the handle. It was almost impossible that she could have been mistaken. Her hands clasped for a moment the necklace which hung from her neck. A queer presentiment of evil crept like a grey shadow over her.

She looked at herself in the glass—the colour had left her cheeks. She tried to laugh at her self.

“This is absurd!” she exclaimed. “Lenora, go down and ask Macdougal to come up for a minute. I am going to have this thing explained. Hurry, there’s a good girl.”

“You are sure your ladyship doesn’t mind being left?” the maid asked, a little doubtfully.

“Of course not!” Ella replied, with a laugh which was not altogether natural. “Hurry along, there’s a good girl. I’ll drink my chocolate while you are gone, and get ready for bed, but I must see Macdougal before I undress.”

Something of her mistress’s agitation seemed to have become communicated to Lenora. Her voice shook a little as she stepped into the elevator.

“Where are you off to, young lady?” the boy enquired.

“I want to go round to our quarters,” Lenora explained. “Her ladyship wants to speak to Mr. Macdougal.”

“He’s gone out, sure,” the elevator boy remarked. “Shall I wait for you, Miss Lenora?” he asked, as they descended into the hall.

“Do,” she begged. “I sha’n’t be more than a minute or two.”

She walked quickly to the back part of the hotel and ascended in another elevator to the wing in which the servants’ quarters were situated. Here she made her way along a corridor until she reached Macdougal’s room. She knocked, and knocked again. There was no answer. She tried the door and found it was locked. Then she returned to the elevator and descended once more to the floor upon which her mistress’s apartments were situated. She opened the door of the suite without knocking and turned at once to the sitting-room.

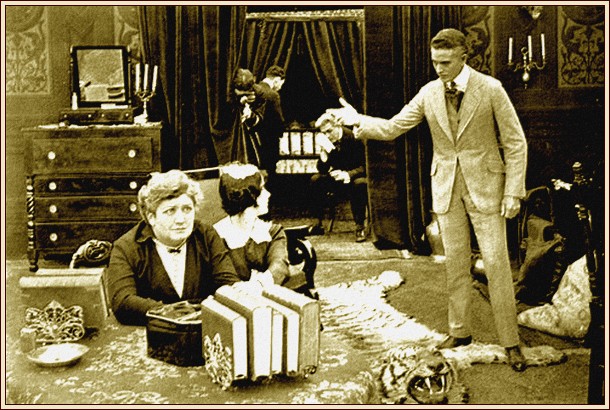

“I am sorry, my lady,” she began—

Then she stopped short. The elevator boy, who had had a little trouble with his starting apparatus and had not as yet descended, heard the scream which broke from her lips, and a fireman in an adjacent corridor came running up almost at the same moment. Lenora was on her knees by her mistress’s side. Ella was still lying in the easy-chair in which she had been seated, but her head was thrown back in an unnatural fashion. There was a red mark just across her throat. The small table by her side had been overturned, and the chocolate was running in a little stream across the floor. The elevator boy was the first to speak.

“Holy shakes!” he exclaimed. “What’s happened?”

“Can’t you see?” Lenora shrieked. “She’s fainted! And the diamonds—the diamonds have gone!”

The fireman was already at the telephone. In less than a minute one of the managers from the office came running in. Lenora was dashing water into Ella’s still, cold face.

“She’s fainted!” she shrieked. “Fetch a doctor, some one. The diamonds have gone!”

The young man was already at the telephone. His hand shook as he took up the receiver. He turned to the elevator boy.

“Run across to number seventy-three—Doctor Morton’s,” he ordered. “Don’t you let any one come in, fireman. Don’t either of you say a word about this. Here, Exchange, urgent call. Give me the police-station—yes, police-station!… Don’t be a fool, girl,” he added under his breath. “You won’t do any good throwing water on her like that. Let her alone for a moment…. Yes! Manager, Leeland Hotel, speaking. A murder and robbery have taken place in this hotel, suite number forty-three. I am there now. Nothing shall be touched. Send round this moment.”

The young man hung up the receiver. Lenora was filling the room with her shrieks. He took her by the shoulder and pushed her back into a chair.

“Shut up, you fool!” he exclaimed. “You can’t do any good making a noise like that.”

“She said she saw the door handle turn,” Lenora sobbed. “I went to fetch Macdougal. He’d gone out. When I came back she was there—like that!”

“What door handle?” the manager asked.

Lenora pointed. The young man crossed the room. The lock was still in its place, the door refused to yield. As he turned around the doctor arrived. He hurried at once to Ella’s side.

“Hands still warm,” he muttered, as he felt them…. “My God! It’s the double knot strangle!”

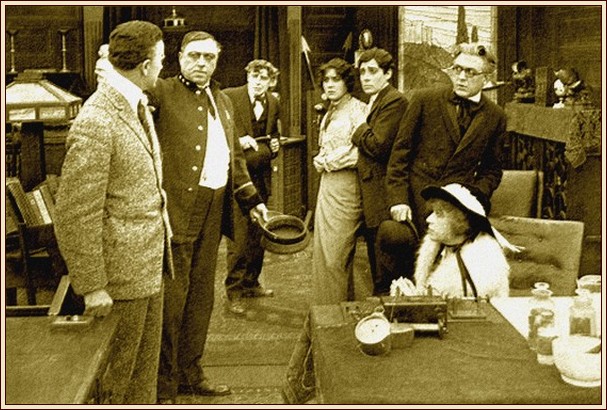

He bent over Ella for several moments. Then he rose to his feet. The door from outside had been opened once more. A police inspector, followed by a detective, had entered.

“This is your affair, gentlemen, not mine,” the doctor said gravely. “The young lady is dead. She has been cruelly strangled within the last five or ten minutes.”

The Inspector turned around.

“Lock the outside door,” he ordered his man. “Has any one left the room, Mr. Marsham?”

“No one,” the manager declared.

“Who discovered her?”

“The maid.”

Lenora rose to her feet. She seemed a little calmer but the healthy colour had all gone from her cheeks and her lips were twitching.

“Her ladyship had just come in from the Opera,” she said. “She was sitting in her easy-chair. I was in the bedroom. She looked toward the handle of that door. She thought it moved. She called me. I tried it and found it fast locked. She sent for Mr. Macdougal.”

“Macdougal,” Mr. Marsham explained, “is a confidential servant of Lord Ashleigh’s. He was sent over here with Lady Ella.”

The Inspector nodded.

“Go on.”

“I found Mr. Macdougal’s door locked. He must have gone out. When I came back here, I found this!”

The Inspector made a careful examination of the room.

“Tell me,” he enquired, “is this the young lady who owned the wonderful Ashleigh diamonds?”

“They’ve gone!” Lenora shrieked. “They’ve been stolen! She was wearing them when I left the room!”

The Inspector turned to the telephone.

“Mr. Marsham,” he said, “I am afraid this will be a difficult affair. I am going to take the liberty of calling in an expert. Hello. I want Number One, New York City—Mr. Sanford Quest.”

Sanford Quest is called upon to clear the

mystery of the murder of Lord Ashleigh’s daughter.

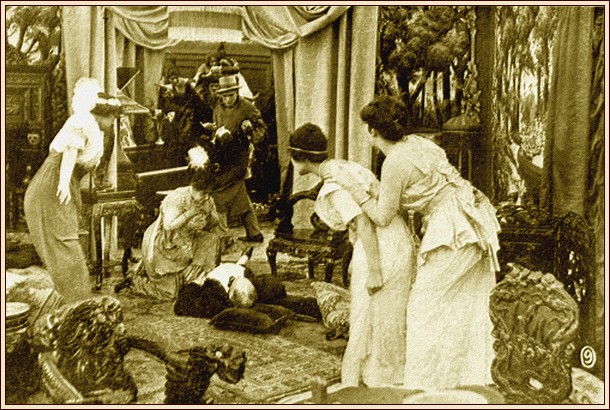

There seemed to be nothing at all original in the methods pursued by the great criminologist when confronted with this tableau of death and robbery. His remarks to the Inspector were few and perfunctory. He asked only a few languid questions of Macdougal and Lenora, who were summoned to his presence.

“You had left the hotel, I understand, at the time when the crime occurred?” he asked the latter.

Macdougal, grave and respectful, made his answers with difficulty. His voice was choked with emotion.

“I brought my mistress home from the Opera, sir. I rode on the box with Mrs. Delarey’s chauffeur. After I had seen her safely in the hotel, I went up to my room for two minutes and left the hotel by the back entrance.”

“Any one see you go?”

“The door-keeper, sir, and I passed a page upon the stairs.”

“Wasn’t it rather late for you to go out?”

“My days are a little dull here, sir,” Macdougal replied, “and my attendance is not required early in the morning. I have made some friends in the city and I usually go out to a restaurant and have some supper.”

“Quite natural,” Mr. Quest agreed. “That will do, thanks.”

Macdougal turned towards the door. Lenora was about to follow him but Quest signed to her to remain.

“I should like to have a little conversation with you about your mistress,” he said to her pleasantly. “If you don’t mind, I will ask you to accompany me in my car. I will send the man back with you.”

For a moment the girl stood quite still. Her face was already ghastly pale. Her eyes alone seemed to indicate some fresh fear.

“I will go to my rooms and put on my hat,” she said.

Quest pointed through the half-open door.

“That will be your hat and coat upon the bed there, won’t it?” he remarked. “I am sorry to hurry you off but I have another appointment. You will send, of course, for the young lady’s friends,” he added, turning to Mr. Marsham, “and cable her people.”

“There is nothing more you can do, Mr. Quest?” the hotel manager asked, a little querulously. “This affair must be cleared up for the credit of my hotel.”

Quest shrugged his shoulders. He glanced through the open door to where Lenora was arranging her coat with trembling fingers.

“There will be very little difficulty about that,” he said calmly. “If you are quite ready, Miss Lenora. Is that your name?”

“Lenora is my name, sir,” the girl replied.

They descended in the elevator together and Quest handed the girl into his car. They drove quickly through the silent streets. The snow had ceased to fall and the stars were shining brightly. Lenora shivered as she leaned back in her corner.

“You are cold, I am afraid,” Quest remarked. “Never mind, there will be a good fire in my study. I shall only keep you for a few moments. I dare not be away long just now, as I have a very important case on.”

“There is nothing more that I can tell you,” Lenora ventured, a little fearfully. “Can’t you ask me what you want to, now, as we go along?”

“We have already arrived,” Quest told her. “Do you mind following me?”

She crossed the pavement and passed through the front door, which Quest was holding open for her. They stepped into the little elevator, and a moment or two later Lenora was installed in an easy-chair in Quest’s sitting-room, in front of a roaring fire.

“Lean back and make yourself comfortable,” Quest invited, as he took a chair opposite to her. “I must just look through these papers.”

The girl did as she was told. She opened her coat. The room was delightfully warm, almost overheated. A sense of rest crept over her. For the first moment since the awful shock, her nerves seemed quieter. Gradually she began to feel almost as though she were passing into sleep. She started up, but sank back again almost immediately. She was conscious that Quest had laid down the letters which he had been pretending to read. His eyes were fixed upon her. There was a queer new look in them, a strange new feeling creeping through her veins. Was she going to sleep?…

Quest’s voice broke an unnatural silence.

“You are anxious to telephone some one,” he said.

“You looked at both of the booths as we came through the hotel. Then you remembered, I think, that he would not be there yet. Telephone now. The telephone is at your right hand. You know the number.”

She obeyed almost at once. She took the receiver from the instrument by her side.

“Number 700, New York City.”

“You will ask,” Quest continued, “whether he is all right, whether the jewels are safe.”

There was a brief silence, then the girl’s voice.

“Are you there, James?… Yes, I am Lenora. Are you safe? Have you the jewels?… Where?… You are sure that you are safe…. No, nothing fresh has happened.”

“You are at the hotel,” Quest said softly. “You are going to him.”

“I cannot sleep,” she continued. “I am coming to you.”

She set down the receiver. Quest leaned a little more closely over her.

“You know where the jewels are hidden,” he said. “Tell me where?”

Her lips quivered. She made no answer. She turned uneasily in her chair.

“Tell me the place?” Quest persisted.

There was still no response from the girl. There were drops of perspiration on her forehead. Quest shrugged his shoulders slightly.

“Very good,” he concluded. “You need not tell me. Only remember this! At nine o’clock to-morrow morning you will bring those jewels to this apartment…. Rest quietly now. I want you to go to sleep.”

She obeyed without hesitation. Quest watched, for a moment, her regular breathing. Then he touched a bell by his side. Laura entered almost at once.

“Open the laboratory,” Quest ordered. “Then come back.”

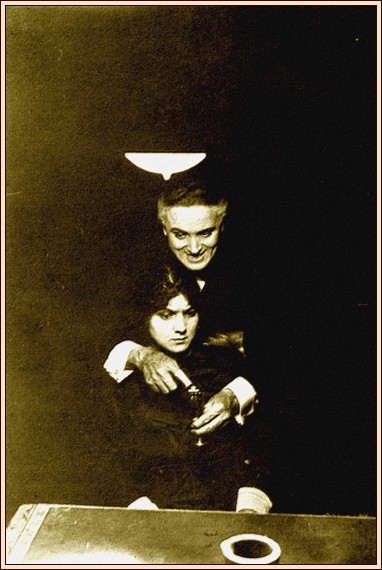

Without a word or a glance towards the sleeping figure, she obeyed him. It was a matter of seconds before she returned. Together they lifted and carried the sleeping girl out of the room, across the landing, into a larger apartment, the contents of which were wrapped in gloom and mystery. A single electric light was burning on the top of a square mirror fixed upon an easel. Towards this they carried the girl and laid her in an easy-chair almost opposite to it.

“The battery is just on the left,” Laura whispered.

Quest nodded.

“Give me the band.”

She turned away for a moment and disappeared in the shadows. When she returned, she carried a curved band of flexible steel. Quest took it from her, attached it by means of a coil of wire to the battery, and with firm, soft fingers slipped it on to Lenora’s forehead. Then he stepped back. A rare emotion quivered in his tone.

“She’s a subject, Laura—I’m sure of it! Now for our great experiment!”

They watched Lenora intently. Her face twitched uneasily, but she did not open her eyes and her breathing continued regular. Quest bent over her.

“Lenora,” he said, slowly and firmly, “your mind is full of one subject. You see your mistress in her chair by the fireside. She is toying with her diamonds. Look again. She lies there dead! Who was it entered the room, Lenora? Look! Look! Gaze into that mirror. What do you see there?”

The girl’s eyes had opened. They were fixed now upon the mirror—distended, full of unholy things. Quest wiped a drop of perspiration from his forehead.

“Try harder, Lenora,” he muttered, his own breath labouring. “It is there in your brain! Look!”

Laura for the first time showed signs of emotion. She pointed towards the mirror. Quest was suddenly silent. He seemed to have turned into a figure of stone. For a single second the smooth surface of the mirror was obscured. A room crept dimly like a picture into being, a fire upon the hearth, a girl leaning back in her chair. A door in the background opened. A man stole out. He crept nearer to the girl—his eyes fixed upon the diamonds, a thin, silken cord twisted round his wrist. Suddenly she saw him—too late! His hand was upon her lips,—his face seemed to start almost from the mirror—then blackness!

Under the hypnotic influence of Quest, Lenora

reveals

the strange disappearance of the jewels, and the murder.

* * * * *

Lenora opened her eyes. She was still in the easy-chair before the fire.

“Mr. Quest!” she faltered.

He looked up from some letters which he had been studying.

“I am so sorry,” he said politely. “I really had forgotten that you were here. But you know—that you have been to sleep?”

She half rose to her feet. She was perplexed, uneasy.

“Asleep?” she murmured. “Have I? And I dreamed a horrible dream!… Have I been ringing anyone up on the telephone?”

“Not that I know of,” Quest assured her. “As a matter of fact, I was called downstairs to see one of my men soon after we got here.”

“Can I go now?” she asked.

“Certainly,” Quest replied. “To tell you the truth, I find that I shall not need to ask you those questions, after all. A messenger from the police-station has been here. He says they have come to the conclusion that a very well-known gang of New York criminals are in this thing. We know how to track them down all right.”

“I may go now, then?” she repeated, with immense relief.

Quest escorted the girl downstairs, opened the front door, blew his whistle and his car pulled up at the door.

“Take this young lady,” he ordered, “wherever she wishes. Good night!”

The girl drove off. Quest watched the car disappear around the corner. Then he turned slowly back and made preparations for his adventure….

“Number 700, New York,” he muttered, half an hour later, as he left his house. “Beyond Fourteenth Street—a tough neighbourhood.”

He hesitated for a moment, feeling the articles in his overcoat pocket—a revolver in one, a small piece of hard substance in the other. Then he stepped into his car, which had just returned.

“Where did you leave the young lady?” he asked the chauffeur.

“In Broadway, sir. She left me and boarded a cross-town car.”

Quest nodded approvingly.

“No finesse,” he sighed.

Sanford Quest was naturally a person unaffected by presentiments or nervous fears of any sort, yet, having advanced a couple of yards along the hallway of the house which he had just entered without difficulty, he came to a standstill, oppressed with the sense of impending danger. With his electric torch he carefully surveyed the dilapidated staircase in front of him, the walls from which the paper hung down in depressing-looking strips. The house was, to all appearances, uninhabited. The door had yielded easily to his master-key. Yet this was the house connected with Number 700, New York, the house to which Lenora had come. Furthermore, from the street outside he had seen a light upon the first floor, instantly extinguished as he had climbed the steps.

“Any one here?” he asked, raising his voice a little.

There was no direct response, yet from somewhere upstairs he heard the half smothered cry of a woman. He gripped his revolver in his fingers. He was a fatalist, and although for a moment he regretted having come single-handed to such an obvious trap, he prepared for his task. He took a quick step forward. The ground seemed to slip from beneath his feet. He staggered wildly to recover himself, and failed. The floor had given from beneath him. He was falling into blackness….

The fall itself was scarcely a dozen feet. He picked himself up, his shoulder bruised, his head swimming a little. His electric torch was broken to pieces upon the stone floor. He was simply in a black gulf of darkness. Suddenly a gleam of light shone down. A trap-door above his head was slid a few inches back. The flare of an electric torch shone upon his face, a man’s mocking voice addressed him.

“Not the great Sanford Quest? This surely cannot be the greatest detective in the world walking so easily into the spider’s web!”

“Any chance of getting out?” Quest asked laconically.

“None!” was the bitter reply. “You’ve done enough mischief. You’re there to rot!”

“Why this animus against me, my friend Macdougal?” Quest demanded. “You and I have never come up against one another before. I didn’t like the life you led in New York ten years ago, or your friends, but you’ve suffered nothing through me.”

“If I let you go,” once more came the man’s voice, “I know very well in what chair I shall be sitting before a month has passed. I am James Macdougal, Mr. Sanford Quest, and I have got the Ashleigh diamonds, and I have settled an old grudge, if not of my own, of one greater than you. That’s all. A pleasant night to you!”

The door went down with a bang. Faintly, as though, indeed, the footsteps belonged to some other world, Sanford Quest heard the two leave the house. Then silence.

“A perfect oubliette,” he remarked to himself, as he held a match over his head a moment or two later, “built for the purpose. It must be the house we failed to find which Bill Taylor used to keep before he was shot. Smooth brick walls, smooth brick floor, only exit twelve feet above one’s head. Human means, apparently, are useless. Science, you have been my mistress all my days. You must save my life now or lose an earnest disciple.”

He felt in his overcoat pocket and drew out the small, hard pellet. He gripped it in his fingers, stood as nearly as possible underneath the spot from which he had been projected, coolly swung his arm back, and flung the black pebble against the sliding door. The explosion which followed shook the very ground under his feet. The walls cracked about him. Blue fire seemed to be playing around the blackness. He jumped on one side, barely in time to escape a shower of bricks. For minutes afterwards everything around him seemed to rock. He struck another match. The whole of the roof of the place was gone. By building a few bricks together, he was easily able to climb high enough to swing himself on to the fragments of the hallway. Even as he accomplished this, the door was thrown open and a crowd of people rushed in. Sanford Quest emerged, dusty but unhurt, and touched a constable on his arm.

“Arrest me,” he ordered. “I am Sanford Quest. I must be taken at once to headquarters.”

“That so, Mr. Quest? Stand on one side, you loafers,” the man ordered, pushing his way out.

“We’ll have a taxicab,” Quest decided.

“Is there any one else in the house?” the policeman asked.

“Not a soul,” Quest answered.

They found a cab without much difficulty. It was five o’clock when they reached the central police-station. Inspector French happened to be just going off duty. He recognized Quest with a little exclamation.

“Got your man to bring me here,” Quest explained, “so as to get away from the mob.”

“Say, you’ve been in trouble!” the Inspector remarked, leading the way into his room.

“Bit of an explosion, that’s all,” Quest replied. “I shall be all right when you’ve lent me a clothes-brush.”

“The Ashleigh diamonds, eh?” the Inspector asked eagerly.

“I shall have them at nine o’clock this morning,” Sanford Quest promised, “and hand you over the murderer somewhere around midnight.”

The Inspector scratched his chin.

“From what I can hear about the young lady’s friends,” he said, “it’s the murderer they are most anxious to see nabbed.”

“They’ll have him,” Quest promised. “Come round about half-past nine and I’ll hand over the diamonds to start with.”

Quest slept for a couple of hours, had a bath and made a leisurely toilet. At a quarter to nine he sat down to breakfast in his rooms.

“At nine o’clock,” he told his servant, “a young lady will call. Bring her up.”

The door was suddenly opened. Lenora walked in. Quest glanced in surprise at the clock.

“My fault!” he exclaimed. “We are slow. Good morning, Miss Lenora!”

She came straight to the table. The servant, at a sign from Quest, disappeared. There were black rims around her eyes; she seemed exhausted. She laid a little packet upon the table. Quest opened it coolly. The Ashleigh diamonds flashed up at him. He led Lenora to a chair and rang the bell.

“Prepare a bedroom upstairs,” he ordered. “Ask Miss Roche to come here. Laura,” he added, as his secretary entered, “will you look after this young lady? She is in a state of nervous exhaustion.”

The girl nodded. She understood. She led Lenora from the room. Quest resumed his breakfast. A few minutes later, Inspector French was announced. Quest nodded in friendly manner.

“Some coffee, Inspector?”

“I’d rather have those diamonds!” the Inspector replied.

Quest threw them lightly across the table.

“Catch hold, then.”

The Inspector whistled.

“Say, that’s bright work,” he acknowledged. “I believe I could have laid my hands on the man, but it was the jewels that I was afraid of losing.”

“Just so,” Quest remarked. “And now, French, will you be here, please, at midnight with three men, armed.”

“Here?” the Inspector repeated.

Quest nodded.

“Our friend,” he said, “is going to be mad enough to walk into hell, even, when he finds out what he thinks has happened.”

“It wasn’t any of Jimmy’s lot?” the Inspector asked.

Sanford Quest shook his head.

“French,” he said, “keep mum, but it was the elderly family retainer, Macdougal. I felt restless about him. He has lost the girl—he was married to her, by-the-bye—and the jewels. No fear of his slipping away. I shall have him here at the time I told you.”

“You’ve a way of your own of doing these things, Mr. Quest,” the Inspector admitted grudgingly.

“Mostly luck,” Quest replied. “Take a cigar, and so long, Inspector. They want me to talk to Chicago on another little piece of business.”

* * * * *

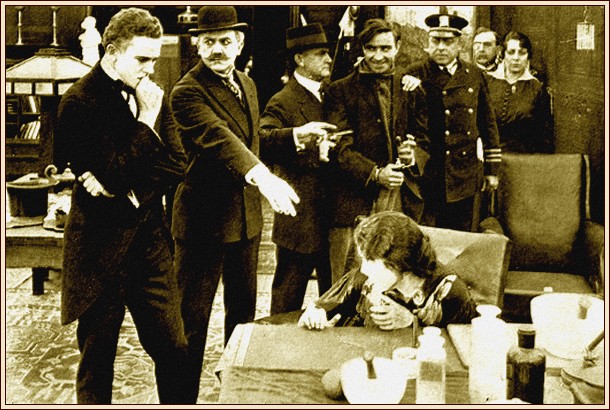

It was a few minutes before midnight when Quest parted the curtains of a room on the ground floor of his house in Georgia Square, and looked out into the snow-white street. Then he turned around and addressed the figure lying as though asleep upon the sofa by the fire.

“Lenora,” he said, “I am going out. Stay here, if you please, until I return.”

He left the room. For a few moments there was a profound silence. Then a white face was pressed against the window. There was a crash of glass. A man, covered with snow, sprang into the apartment. He moved swiftly to the sofa, and something black and ugly swayed in his hand.

“So you’ve deceived me, have you?” he panted. “Handed over the jewels, chucked me, and given me the double cross! Anything to say?”

A piece of coal fell on to the grate. Not a sound came from the sofa. Macdougal leaned forward, his white face distorted with passion. The life-preserver bent and quivered behind him, cut the air with a swish and crashed full upon the head.

The man staggered back. The weapon fell from his fingers. For a moment he was paralysed. There was no blood upon his hand, no cry—silence inhuman, unnatural! He looked again. Then the lights flashed out all around him. There were two detectives in the doorway, their revolvers covering him,—Sanford Quest, with Lenora in the background. In the sudden illumination, Macdougal’s horror turned almost to hysterical rage. He had wasted his fury upon a dummy! It was sawdust, not blood, which littered the couch!

“Take him, men,” Quest ordered. “Hands up, Macdougal. Your number’s up. Better take it quietly.”

The handcuffs were upon him before he could move. He was trying to speak, but the words somehow choked in his mouth.

“You can send a wireless to Lord Ashleigh,” Quest continued, turning to French. “Tell him that the diamonds have been recovered and that his daughter’s murderer is arrested.”

“What about the young woman?” the Inspector asked.

Lenora stood in an attitude of despair, her head downcast. She had turned a little away from Macdougal. Her hands were outstretched. It was as though she were expecting the handcuffs.

“You can let her alone,” Sanford Quest said quietly. “A wife cannot give evidence against her husband, and besides, I need her. She is going to work for me.”

Lord Ashleigh accuses Lenora of being implicated

in the crime, but Quest decides to the contrary.

Macdougal was already at the door, between the two detectives. He swung around. His voice was calm, almost clear—calm with the concentration of hatred.

“You are a wonderful man, Mr. Sanford Quest,” he said. “Make the most of your triumph. Your time is nearly up.”

“Keep him for a moment,” Sanford Quest ordered. “You have friends, then, Macdougal, who will avenge you, eh?”

“I have no friends,” Macdougal replied, “but there is one coming whose wit and cunning, science and skill are all-conquering. He will brush you away, Sanford Quest, like a fly. Wait a few weeks.”

“You interest me,” Quest murmured. “Tell me some more about this great master?”

“I shall tell you nothing,” Macdougal replied. “You will hear nothing, you will know nothing. Suddenly you will find yourself opposed. You will struggle—and then the end. It is certain.”

They led him away. Only Lenora remained, sobbing. Quest went up to her, laid his hand upon her shoulder.

“You’ve had a rough time, Lenora,” he said, with strange gentleness. “Perhaps the brighter days are coming.”

Sanford Quest and Lenora stood side by side upon the steps of the Courthouse, waiting for the automobile which had become momentarily entangled in a string of vehicles. A little crowd of people were elbowing their way out on to the sidewalk. The faces of most of them were still shadowed by the three hours of tense drama from which they had just emerged. Quest, who had lit a cigar, watched them curiously.

Ian Macdougal is given a life sentence for

the murder of the daughter of Lord Ashleigh.

“No need to go into Court,” he remarked. “I could have told you, from the look of these people, that Macdougal had escaped the death sentence. They have paid their money—or rather their time, and they have been cheated of the one supreme thrill.”

“Imprisonment for life seems terrible enough,” Lenora whispered, shuddering.

“Can’t see the sense of keeping such a man alive myself,” Quest declared, with purposeful brutality. “It was a cruel murder, fiendishly committed.”

Lenora shivered. Quest laid his fingers for a moment upon her wrist. His voice, though still firm, became almost kind.

“Never be afraid, Lenora,” he said, “to admit the truth. Come, we have finished with Macdougal now. Imprisonment for life will keep him from crossing your path again.”

Lenora sighed. She was almost ashamed of her feeling of immense relief.

“I am very sorry for him,” she murmured. “I wish there were something one could do.”

“There is nothing,” Quest replied shortly, “and if there were, you would not be allowed to undertake it. You didn’t happen to notice the way he looked at you once or twice, did you?”

Once more the terror shone out of Lenora’s eyes.

“You are right,” she faltered. “I had forgotten.”

They were on the point of crossing the pavement towards the automobile when Quest felt a touch upon his shoulder. He turned and found Lord Ashleigh standing by his side. Quest glanced towards Lenora.

“Run and get in the car,” he whispered. “I will be there in a moment.”

She dropped her veil and hastened across the pavement. The Englishman’s face grew sterner as he watched her.

“Macdougal’s accomplice,” he muttered. “We used to trust that girl, too.”

“She had nothing whatever to do with the actual crime, believe me,” Quest assured him. “Besides, you must remember that it was really through her that the man was brought to justice.”

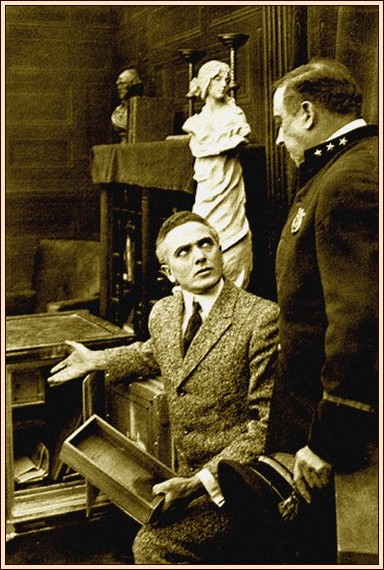

“I harbour no ill-feelings towards the girl,” Lord Ashleigh replied. “Nevertheless, the sight of her for a moment was disconcerting…. I would not have stopped you just now, Mr. Quest, but my brother is very anxious to renew his acquaintance with you. I think you met years ago.”

Sanford Quest held out his hand to the man who had been standing a little in the background. Lord Ashleigh turned towards him.

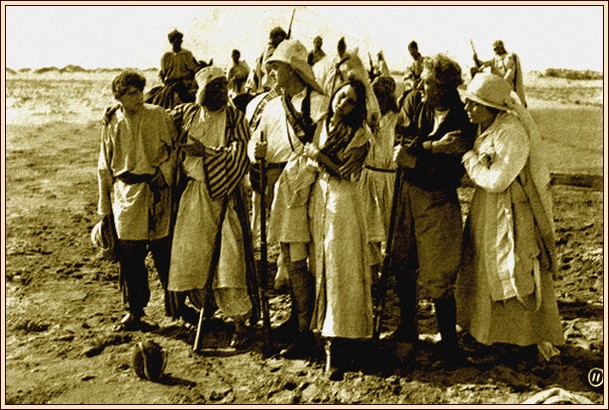

“This is Mr. Quest, Edgar. You may remember my brother—Professor Ashleigh—as a man of science, Quest? He has just returned from South America.”

The two shook hands, curiously diverse in type, in expression, in all the appurtenances of manhood. Quest was dark, with no sign of greyness in his closely-trimmed black hair. His face was an epitome of forcefulness, his lips hard, his eyes brilliant. He was dressed with the utmost care. His manner was self-possessed almost to a fault. The Professor, on the other hand, though his shoulders were broad, lost much of his height and presence through a very pronounced stoop. His face was pale, his mouth sensitive, his smile almost womanly in its sweetness. His clothes, and a general air of abstraction, seemed rather to indicate the clerical profession. His forehead, however, disclosed as he lifted his hat, was the forehead of a scholar.

“I am very proud to make your acquaintance again, Professor,” Quest said. “Glad to know, too, that you hadn’t quite forgotten me.”

“My dear sir,” the Professor declared, as he released the other’s hand with seeming reluctance, “I have thought about you many times. Your doings have always been of interest to me. Though I have been lost to the world of civilisation for so long, I have correspondents here in New York to keep me in touch with all that is interesting. You have made a great name for yourself, Mr. Quest. You are one of those who have made science your handmaiden in a wonderful profession.”

“You are very kind, Professor,” Quest observed, flicking the ash from his cigar.

“Not at all,” the other insisted. “Not at all. I have the greatest admiration for your methods.”

“I am sorry,” Quest remarked, “that our first meeting here should be under such distressing circumstances.”

The Professor nodded gravely. He glanced towards his brother, who was talking to an acquaintance a few feet away.

“It has been a most melancholy occasion,” he admitted, his voice shaking with emotion. “Still, I felt it my duty to support my brother through the trial. Apart from that, you know, Mr. Quest, a scene such as we have just witnessed has a peculiar—I might almost say fascination for me,” the Professor continued, with a little glint in his eyes. “You, as a man of science, can realise, I am sure, that the criminal side of human nature is always of interest to an anthropologist.”

“That must be so, of course,” Quest agreed, glancing towards the automobile in which Lenora was seated. “If you’ll excuse me, Professor, I think I must be getting along. We shall meet again, I trust.”

“One moment,” the Professor begged eagerly. “Tell me, Mr. Quest—I want your honest opinion. What do you think of my ape?”

“Of your what?” Quest enquired dubiously.

“Of my anthropoid ape which I have just sent to the museum. You know my claim? But perhaps you would prefer to postpone your final decision until after you have examined the skeleton itself.”

A light broke in upon the criminologist.

“Of course!” he exclaimed. “For the moment, Professor, I couldn’t follow you. You are talking about the skeleton of the ape which you brought home from South America, and which you have presented to the museum here?”

“Naturally,” the Professor assented, with mild surprise. “To what else? I am stating my case, Mr. Quest, in the North American Review next month. I may tell you, however, as a fellow scientist, the great and absolute truth. My claim is incontestable. My skeleton will prove to the world, without a doubt, the absolute truth of Darwin’s great theory.”

“That so?”

“You must go and see it,” the Professor insisted, keeping by Quest’s side as the latter moved towards the automobile. “You must go and see it, Mr. Quest. It will be on view to the public next week, but in the meantime I will telephone to the curator. You must mention my name. You shall be permitted a special examination.”

“Very kind of you,” Quest murmured.

“We shall meet again soon, I hope,” the Professor concluded cordially. “Good morning, Mr. Quest!”

The two men shook hands, and Quest took his seat by Lenora’s side in the automobile. The Professor rejoined his brother.

“George,” he exclaimed, as they walked off together, “I am disappointed in Mr. Quest! I am very disappointed indeed. You will not believe what I am going to tell you, but it is the truth. He could not conceal it from me. He takes no interest whatever in my anthropoid ape.”

“Neither do I,” the other replied grimly.

The Professor sighed as he hailed a taxicab.

“You, my dear fellow,” he said gravely, “are naturally not in the frame of mind for the consideration of these great subjects. Besides, you have no scientific tendencies. But in Sanford Quest I am disappointed. I expected his enthusiasm—I may say that I counted upon it.”

“I don’t think that Quest has much of that quality to spare,” his brother remarked, “for anything outside his own criminal hunting.”

They entered the taxicab and were driven almost in silence to the Professor’s home—a large, rambling old house, situated in somewhat extensive but ill-kept grounds on the outskirts of New York. The Englishman glanced around him, as they passed up the drive, with an expression of disapproval.

“A more untidy-looking place than yours, Edgar, I never saw,” he declared. “Your grounds have become a jungle. Don’t you keep any gardeners?”

The Professor smiled.

“I keep other things,” he said serenely. “There is something in my garden which would terrify your nice Scotch gardeners into fits, if they found their way here to do a little tidying up. Come into the library and I’ll give you one of my choice cigars. Here’s Craig waiting to let us in. Any news, Craig?”

The man-servant in plain clothes who admitted them shook his head.

“Nothing has happened, sir,” he replied. “The telephone is ringing in the study now, though.”

“I will answer it myself,” the Professor declared, bustling off.

He hurried across the bare landing and into an apartment which seemed to be half museum, half library. There were skeletons leaning in unexpected corners, strange charts upon the walls, a wilderness of books and pamphlets in all manner of unexpected places, mingled with quaintly-carved curios, gods from West African temples, implements of savage warfare, butterfly nets. It was a room which Lord Ashleigh was never able to enter without a shudder.

The Professor took up the receiver from the telephone. His “Hello” was mild and enquiring. He had no doubt that the call was from some admiring disciple. The change in his face as he listened, however, was amazing. His lips began to twitch. An expression of horrified dismay overspread his features. His first reply was almost incoherent. He held the receiver away from him and turned towards his brother.

“George,” he gasped, “the greatest tragedy in the world has happened! My ape is stolen!”

His brother looked at him blankly.

“Your ape is stolen?” he repeated.

“The skeleton of my anthropoid ape,” the Professor continued, his voice growing alike in sadness and firmness. “It is the curator of the museum who is speaking. They have just opened the box. It has lain for two days in an anteroom. It is empty!”

Lord Ashleigh muttered something a little vague. The theft of a skeleton scarcely appeared to his unscientific mind to be a realisable thing. The Professor turned back to the telephone.

“Mr. Francis,” he said, “I cannot talk to you. I can say nothing. I shall come to you at once. I am on the point of starting. Your news has overwhelmed me.”

He laid down the receiver. He looked around him like a man in a nightmare.

“The taxicab is still waiting, sir,” Craig reminded him.

“That is most fortunate,” the Professor pronounced. “I remember now that I had no change with which to pay him. I must go back. Look after my brother. And, Craig, telephone at once to Mr. Sanford Quest. Ask him to meet me at the museum in twenty minutes. Tell him that nothing must stand in the way. Do you hear?”

The man hesitated. There was protest in his face.

“Mr. Sanford Quest, sir?” he muttered, as he followed his master down the hall.

“The great criminologist,” the Professor explained eagerly. “Certainly! Why do you hesitate?”

“I was wondering, sir,” Craig began.

The Professor waved his servant on one side.

“Do as you are told,” he ordered. “Do as you are told, Craig. You others—you do not realise. You cannot understand what this means. Tell the taxi man to drive to the museum. I am overcome.”

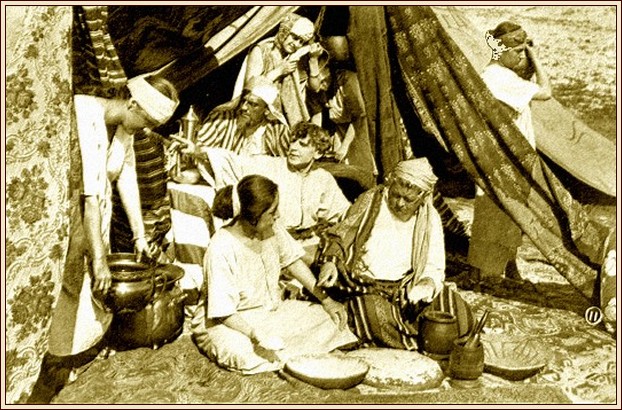

The taxicab man drove off, glad enough to have a return fare. In about half-an-hour’s time the Professor strode up the steps of the museum and hurried into the office. There was a little crowd of officials there whom the curator at once dismissed. He rose slowly to his feet. His manner was grave but bewildered.

“Professor,” he said, “we will waste no time in words. Look here.”

He threw open the door of an anteroom behind his office. The apartment was unfurnished except for one or two chairs. In the middle of the uncarpeted floor was a long wooden box from which the lid had just been pried.

“Yesterday, as you know from my note,” the curator proceeded, “I was away. I gave orders that your case should be placed here and I myself should enjoy the distinction of opening it. An hour ago I commenced the task. That is what I found.”

The Professor gazed blankly at the empty box.

“Nothing left except the smell,” a voice from the open doorway remarked.

They glanced around. Quest was standing there, and behind him Lenora. The Professor welcomed them eagerly.

“This is Mr. Quest, the great criminologist,” he explained to the curator. “Come in, Mr. Quest. Let me introduce you to Mr. Francis, the curator of the museum. Ask him what questions you will. Mr. Quest, you have the opportunity of earning the undying gratitude of a brother scientist. If my skeleton cannot be recovered, the work of years is undone.”

Quest strolled thoughtfully around the room, glancing out of each of the windows in turn. He kept close to the wall, and when he had finished he drew out a magnifying-glass from his pocket and made a brief examination of the box. Then he asked a few questions of the curator, pointed out one of the windows to Lenora and whispered a few directions to her. She at once produced what seemed to be a foot-rule from the bag which she was carrying, and hurried into the garden.

“A little invention of my own for measuring foot-prints,” Quest explained. “Not much use here, I am afraid.”

“What do you think of the affair so far, Mr. Quest?” the Professor asked eagerly.

The criminologist shook his head.

“Incomprehensible,” he confessed. “Can you think, by-the-bye, of any other motive for the theft besides scientific jealousy?”

“There could be no other,” the Professor declared sadly, “and it is, alas! too prevalent. I have had to suffer from it all my life.”

Quest stood over the box for a moment or two and looked once more out of the window. Presently Lenora returned. She carried in her hand a small object, which she brought silently to Quest. He glanced at it in perplexity. The Professor peered over his shoulder.

“It is the little finger!” he cried,—“the little finger of my ape!”

Quest held it away from him critically.

“From which hand?” he asked.

“The right hand.”

Quest examined the fastenings of the window before which he had paused during his previous examination. He turned away with a shrug of the shoulders.

“See you later, Mr. Ashleigh,” he concluded laconically. “Nothing more to be done at present.”

The Professor followed him to the door.

“Mr. Quest,” he said, his voice broken with emotion, “it is the work of my lifetime of which I am being robbed. You will use your best efforts, you will spare no expense? I am rich. Your fee you shall name yourself.”

“I shall do my best,” Quest promised, “to find the skeleton. Come, Lenora. Good morning, gentlemen!”

* * * * *

With his new assistant, Quest walked slowly from the museum and turned towards his home.

“Make anything of this, Lenora?” he asked her.

She smiled.

“Of course not,” she answered. “It looks as though the skeleton had been taken away through that window.”

Quest nodded.

“Marvellous!” he murmured.

“You are making fun of me,” she protested.

“Not I! But you see, my young friend, the point is this. Who in their senses would want to steal an anthropoid skeleton except a scientific man, and if a scientific man stole it out of sheer jealousy, why in thunder couldn’t he be content with just mutilating it, which would have destroyed its value just as well—What’s that?”

He stopped short. A newsboy thrust the paper at them. Quest glanced at the headlines. Lenora clutched at his arm. Together they read in great black type—

ESCAPE OF CONVICTED PRISONER!

MACDOUGAL, ON HIS WAY TO PRISON,

GRAPPLES WITH SHERIFF AND JUMPS FROM TRAIN!

STILL AT LARGE THOUGH SEARCHED FOR BY POSSE OF POLICE

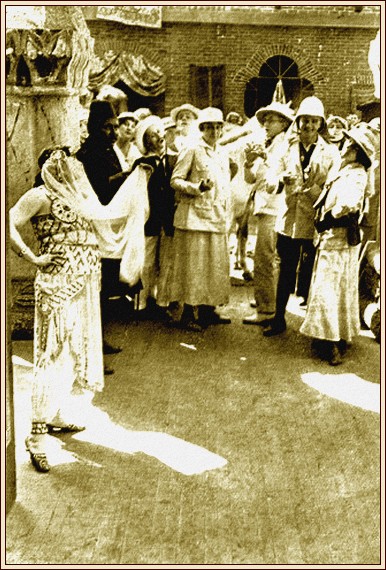

The windows of Mrs. Rheinholdt’s town house were ablaze with light. A crimson drugget stretched down the steps to the curbstone. A long row of automobiles stood waiting. Through the wide-flung doors was visible a pleasant impression of flowers and light and luxury. In the nearer of the two large reception rooms Mrs. Rheinholdt herself, a woman dark, handsome, and in the prime of life, was standing receiving her guests. By her side was her son, whose twenty-first birthday was being celebrated.

“I wonder whether that professor of yours will come,” she remarked, as the stream of incoming guests slackened for a moment. “I’d love to have him here, if it were only for a moment. Every one’s talking about him and his work in South America.”

“He hates receptions,” the boy replied, “but he promised he’d come. I never thought, when he used to drill science into us at the lectures, that he was going to be such a tremendous big pot.”

Mrs. Rheinholdt’s plump fingers toyed for a moment complacently with the diamonds which hung from her neck.

“You can never tell, in a world like this,” she murmured. “That’s why I make a point of being civil to everybody. Your laundry woman may become a multimillionaire, or your singing master a Caruso, and then, just while their month’s on, every one is crazy to meet them. It’s the Professor’s month just now.”

“Here he is, mother!” the young man exclaimed suddenly. “Good old boy! I thought he’d keep his word.”

Mrs. Rheinholdt assumed her most encouraging and condescending smile as she held out both hands to the Professor. He came towards her, stooping a little more than usual. His mouth had drooped a little and there were signs of fatigue in his face. Nevertheless, his answering smile was as delightful as ever.

“This is perfectly sweet of you, Professor,” Mrs. Rheinholdt declared. “We scarcely ventured to hope that you would break through your rule, but Philip was so looking forward to have you come. You were his favourite master at lectures, you know, and now—well, of course, you have the scientific world at your feet. Later on in the evening, Professor,” she added, watching some very important newcomers, “you will tell me all about your anthropoid ape, won’t you? Philip, look after Mr. Ashleigh. Don’t let him go far away.”

Mrs. Rheinholdt breathed a sigh of relief as she greeted her new arrivals.

“Professor Ashleigh, brother of Lord Ashleigh, you know,” she explained. “This is the first house he has been to since his return from South America. You’ve heard all about those wonderful discoveries, of course….”

The Professor made himself universally agreeable in a mild way, and his presence created even more than the sensation which Mrs. Rheinholdt had hoped for. In her desire to show him ample honour, she seldom left his side.

“I am going to take you into my husband’s study,” she suggested, later on in the evening. “He has some specimens of beetles—”

“Beetles,” the Professor declared, with some excitement, “occupied precisely two months of my time while abroad. By all means, Mrs. Rheinholdt!”

“We shall have to go quite to the back of the house,” she explained, as she led him along the darkened passage.

The Professor smiled acquiescently. His eyes rested for a moment upon her necklace.

“You must really permit me, Mrs. Rheinholdt,” he exclaimed, “to admire your wonderful stones! I am a judge of diamonds, and those three or four in the centre are, I should imagine, unique.”

She held them out to him. The Professor laid the end of the necklace gently in the palm of his hand and examined them through a horn-rimmed eyeglass.

“They are wonderful,” he murmured,—“wonderful! Why—”

He turned away a little abruptly. They had reached the back of the house and a door from the outside had just been opened. A man had crossed the threshold with a coat over his arm, and was standing now looking at them.

“How extraordinary!” the Professor remarked. “Is that you, Craig?”

For a moment there was no answer. The servant was standing in the gloom of an unlit portion of the passage. His eyes were fixed curiously upon the diamonds which the Professor had just been examining. He seemed paler, even, than usual.

“Yes, sir!” he replied. “There is a rain storm, so I ventured to bring your mackintosh.”

“Very thoughtful,” the Professor murmured approvingly. “I have a weakness,” he went on, turning to his hostess, “for always walking home after an evening like this. In the daytime I am content to ride. At night I have the fancy always to walk.”

“We don’t walk half enough.” Mrs. Rheinholdt sighed, glancing down at her somewhat portly figure. “Dixon,” she added, turning to the footman who had admitted Craig, “take Professor Ashleigh’s servant into the kitchen and see that he has something before he leaves for home. Now, Professor, if you will come this way.”

They reached a little room in the far corner of the house. Mrs. Rheinholdt apologised as she switched on the electric lights.

“It is a queer little place to bring you to,” she said, “but my husband used to spend many hours here, and he would never allow anything to be moved. You see, the specimens are in these cases.”

The Professor nodded. His general attitude towards the forthcoming exhibition was merely one of politeness. As the first case was opened, however, his manner completely changed. Without taking the slightest further notice of his hostess, he adjusted a pair of horn-rimmed spectacles and commenced to mumble eagerly to himself. Mrs. Rheinholdt, who did not understand a word, strolled around the apartment, yawned, and finally interrupted a little stream of eulogies, not a word of which she understood, concerning a green beetle with yellow spots.

“I am so glad you are interested, Professor,” she said. “If you don’t mind, I will rejoin my guests. You will find a shorter way back if you keep along the passage straight ahead and come through the conservatory.”

“Certainly! With pleasure!” the Professor agreed, without glancing up.

His hostess sighed as she turned to leave the room. She left the door ajar. The Professor’s face was almost touching the glass case in which reposed the green beetle with yellow spots.

* * * * *

Mrs. Rheinholdt’s reception, notwithstanding the temporary absence of its presiding spirit, was without doubt an unqualified success. In one of the distant rooms the younger people were dancing. There were bridge tables, all of which were occupied, and for those who preferred the more old-fashioned pastime of conversation amongst luxurious surroundings, there was still ample space and opportunity. Philip Rheinholdt, with a pretty young débutante upon his arm, came out from the dancing room and looked around amongst the little knots of people.

“I wonder where mother is,” he remarked.

“Looking after some guests somewhere, for certain,” the girl replied. “Your mother is so wonderful at entertaining, Philip.”

“It’s the hobby of her life,” he declared. “Never so happy as when she can get hold of somebody every one’s talking about, and show him off. Can’t think what she’s done with herself now, though. She told me—”