RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

"Jeanne of the Marshes," Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1909

"Jeanne of the Marshes," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1909

| • Book I • Chapter I • Chapter II • Chapter III • Chapter IV • Chapter V • Chapter VI • Chapter VII • Chapter VIII • Chapter IX • Chapter X • Chapter XI • Chapter XII • Chapter XIII • Chapter XIV • Chapter XV • Chapter XVI • Chapter XVII • Chapter XVIII • Chapter XIX • Chapter XX • Chapter XXI |

• Book II • Chapter I • Chapter II • Chapter III • Chapter IV • Chapter V • Chapter VI • Chapter VII • Chapter VIII • Chapter IX • Chapter X • Chapter XI • Chapter XII • Chapter XIII • Chapter XIV • Chapter XV • Chapter XVI • Chapter XVII • Chapter XVIII • Chapter XIX • Chapter XX |

Gunter's Magazine, Jun 1909, with first part of "Jeanne of the Marshes"

Jeanne - Frontispiece

The Princess opened her eyes at the sound of her maid's approach. She turned her head impatiently toward the door.

"Annette," she said coldly, "did you misunderstand me? Did I not say that I was on no account to be disturbed this afternoon?"

Annette was the picture of despair. Eyebrows and hands betrayed alike both her agitation of mind and her nationality.

"Madame," she said, "did I not say so to monsieur? I begged him to call again. I told him that madame was lying down with a bad headache, and that it was as much as my place was worth to disturb her. What did he answer? Only this. That it would be as much as my place was worth if I did not come up and tell you that he was here to see you on a very urgent matter. Indeed, madame, he was very, very impatient with me."

"Of whom are you talking?" the Princess asked.

"But of Major Forrest, madame," Annette declared. "It is he who waits below."

The Princess closed her eyes for a moment and then slowly opened them. She stretched out her hand, and from a table by her side took up a small gilt mirror.

"Turn on the lights, Annette," she commanded.

The maid illuminated the darkened room. The Princess gazed at herself in the mirror, and reaching out again took a small powder-puff from its case and gently dabbed her face. Then she laid both mirror and powder-puff back in their places.

"You will tell monsieur," she said, "that I am very unwell indeed, but that since he is here and his business is urgent I will see him. Turn out the lights, Annette. I am not fit to be seen. And move my couch a little, so."

"Madame is only a little pale," the maid said reassuringly. "That makes nothing. These Englishwomen have all too much colour. I go to tell monsieur."

She disappeared, and the Princess lay still upon her couch, thinking. Soon she heard steps outside, and with a little sigh she turned her head toward the door. The man who entered was tall, and of the ordinary type of well-born Englishmen. He was carefully dressed, and his somewhat scanty hair was arranged to the best advantage. His features were hard and lifeless. His eyes were just a shade too close together. The maid ushered him in and withdrew at once.

"Come and sit by my side, Nigel, if you want to talk to me," the Princess said. "Walk softly, please. I really have a headache."

"No wonder, in this close room," the man muttered, a little ungraciously. "It smells as though you had been burning incense here."

"It suits me," the Princess answered calmly, "and it happens to be my room. Bring that chair up here and say what you have to say."

The man obeyed in silence. When he had made himself quite comfortable, he raised her hand, the one which was nearest to him, to his lips, and afterwards retained it in his own.

"Forgive me if I seem unsympathetic, Ena," he said. "The fact is, everything has been getting on my nerves for the last few days, and my luck seems dead out."

She looked at him curiously. She was past middle age, and her face showed signs of the wear and tear of life. But she still had fine eyes, and the rejuvenating arts of Bond Street had done their best for her.

"What is the matter, Nigel?" she asked. "Have the cards been going against you?"

He frowned and hesitated for a moment before replying.

"Ena," he said, "between us two there is an ancient bargain, and that is that we should tell the truth to one another. I will tell you what it is that is worrying me most. I have suspected it for some time, but this afternoon it was absolutely obvious. There is a sort of feeling at the club. I can't exactly describe it, but I am conscious of it directly I come into the room. For several days I have scarcely been able to get a rubber. This afternoon, when I cut in with Harewood and Mildmay and another fellow, two of them made some sort of an excuse and went off. I pretended not to notice it, of course, but there it was. The thing was apparent, and it is the very devil!"

Again she looked at him closely.

"There is nothing tangible?" she asked. "No complaint, or scandal, or anything of that sort?"

He rejected the suggestion with scorn.

"No!" he said. "I am not such an idiot as that. All the same there is the feeling. They don't care to play bridge with me. There is only young Engleton who takes my part, and so far as playing bridge for money is concerned, he would be worth the whole lot put together if only I could get him away from them—make up a little party somewhere, and have him to myself for a week or two."

The Princess was thoughtful.

"To go abroad at this time of the year," she remarked, "is almost impossible. Besides, you have only just come back."

"Absolutely impossible," he answered. "Besides, I shouldn't care to do it just now. It looks like running away. A week or so ago you were talking of taking a villa down the river. I wondered whether you had thought any more of it."

The Princess shook her head.

"I dare not," she answered. "I have gone already further than I meant to. This house and the servants and carriages are costing me a small fortune. I dare not even look at my bills. Another house is not to be thought of."

Major Forrest looked gloomily at the shining tip of his patent boot.

"It's jolly hard luck," he muttered. "A quiet place somewhere in the country, with Engleton and you and myself, and another one or two, and I should be able to pull through. As it is, I feel inclined to chuck it all."

The Princess looked at him curiously. He was certainly more than ordinarily pale, and the hand which rested upon the side of his chair was twitching a little nervously.

"My dear Nigel," she said, "do go to the chiffonier there and help yourself to a drink. I hate to see you white to the lips, and trembling as though death itself were at your elbow. Borrow a little false courage, if you lack the real thing."

The man obeyed her suggestion with scarcely a protest.

"I had hoped, Ena," he remarked a little peevishly, "to have found you more sympathetic."

"You are so sorry for yourself," she answered, "that you seem scarcely to need my sympathy. However, sit down and talk to me reasonably."

"I talk reasonably enough," he answered, "but I really am hard up against it. Don't think I have come begging. I know you've done all you can, and it's a matter with me now of more than a few hundreds. My only hope is Engleton. Can't you suggest anything?"

The Princess rested her head slightly upon the long slender fingers of her right hand. Bond Street had taken care of her complexion, but the veins in her hand were blue, and art had no means of concealing a certain sharpness of features and the thin lines about the eyes, nameless suggestions of middle age. Yet she was still a handsome woman. She knew how to dress, and how to make the best of herself. She had the foreigner's instinct for clothes, and her figure was still irreproachable. She sat and looked with a sort of calculating interest at the man who for years had come as near touching her heart as any of his sex. Curiously enough she knew that this new aspect in which he now presented himself, this incipient cowardice—the first-fruits of weakening nerves—did not and could not affect her feelings for him. She saw him now almost for the first time with the mask dropped, no longer cold, cynical and calculating, but a man moved to his shallow depths by what might well seem to him, a dweller in the narrow ways of life, as a tragedy. It looked at her out of his grey eyes. It showed itself in the twitching of his lips. For many years he had lived upon a little less than nothing a year. Now for the first time his means of livelihood were threatened. His long-suffering acquaintances had left him alone at the card-table.

"You disappoint me, Nigel," she said. "I hate to see a man weaken. There is nothing against you. Don't act as though there could be. As to this little house-party you were speaking of, I only wish I could think of something to help you. By the by, what are you doing to-night?"

"Nothing," he answered, "except that Engleton is expecting me to dine with him."

"I have an idea," the Princess said slowly. "It may not come to anything, but it is worth trying. Have you met my new admirer, Mr. Cecil de la Borne?"

Forrest shook his head.

"Do you mean a dandified-looking boy whom you were driving with in the Park yesterday?"

The Princess nodded.

"We met him a week or so ago," she answered, "and he has been very attentive. He has a country place down in Norfolk, which from his description is, I should think, like a castle in Hermitland. Jeanne and I are dining with him to-night at the Savoy. You and Engleton must come, too. I can arrange it. It is just possible that we may be able to manage something. He told me yesterday that he was going back to Norfolk very soon. I fancy that he has a brother who keeps rather a strict watch over him, and he is not allowed to stay up in town very long at a time."

"I know the name," Forrest remarked. "They are a very old Roman Catholic family. We'll come and dine, if you say that you can arrange it. But I don't see how we can all hope to get an invitation out of him on such a short acquaintance."

The Princess was looking thoughtful.

"Leave it to me," she said. "I have an idea. Be at the Savoy at a quarter past eight, and bring Lord Ronald."

Forrest took up his hat. He looked at the Princess with something very much like admiration in his face. For years he had dominated this woman. To-day, for the first time, she had had the upper hand.

"We will be there all right," he said. "Engleton will only be too glad to be where Jeanne is. I suppose young De la Borne is the same way."

The Princess sighed.

"Every one," she remarked, "is so shockingly mercenary!"

The Princess helped herself to a salted almond and took her first sip of champagne. The almonds were crisp and the champagne dry. She was wearing a new and most successful dinner-gown of black velvet, and she was quite sure that in the subdued light no one could tell that the pearls in the collar around her neck were imitation. Her afternoon's indisposition was quite forgotten. She nodded at her host approvingly.

"Cecil," she said, "it is really very good of you to take in my two friends like this. Major Forrest has just arrived from Ostend, and I was very anxious to hear about the people I know there, and the frocks, and all the rest of it. Lord Ronald always amuses me, too. I suppose most people would call him foolish, but to me he only seems very, very young."

The young man who was host raised his glass and bowed towards the Princess.

"I can assure you," he said, "that it has given me a great deal of pleasure to make the acquaintance of Major Forrest and Lord Ronald, but it has given me more pleasure still to be able to do anything for you. You know that."

She looked at him quickly, and down at her plate. Such glances had become almost a habit with her, but they were still effectual. Cecil de la Borne leaned across towards Forrest.

"I hear that you have been to Ostend lately, Major Forrest," he said. "I thought of going over myself a little later in the season for a few days."

"I wouldn't if I were you," Forrest answered. "It is overrun just now with the wrong sort of people. There is nothing to do but gamble, which doesn't interest me particularly; or dress in a ridiculous costume and paddle about in a few feet of water, which appeals to me even less."

"You were there a little early in the season," the Princess reminded him.

Major Forrest assented.

"A little later," he admitted, "it may be tolerable. On the whole, however, I was disappointed."

Lord Ronald spoke for the first time. He was very thin, very long, and very tall. He wore a somewhat unusually high collar, but he was very carefully, not to say exactly, dressed. His studs and links and waistcoat buttons were obviously fresh from the Rue de la Paix. The set of his tie was perfection. His features were not unintelligent, but his mouth was weak.

"One thing I noticed about Ostend," he remarked, "they charge you a frightful price for everything. We never got a glass of champagne there like this."

"I am glad you like it," their host said. "From what you say I don't imagine that I should care for Ostend. I am not rich enough to gamble, and as I have lived by the sea all my days, bathing does not attract me particularly. I think I shall stay at home."

"By the by, where is your home, Mr. De la Borne?" the Princess asked. "You told me once, but I have forgotten. Some of your English names are so queer that I cannot even pronounce them, much more remember them."

"I live in a very small village in Norfolk, called Salthouse," Cecil de la Borne answered. "It is quite close to a small market-town called Wells, if you know where that is. I don't suppose you do, though," he added. "It is an out-of-the-way corner of the world."

The Princess shook her head.

"I never heard of it," she said. "I am going to motor through Norfolk soon, though, and I think that I shall call upon you."

Cecil de la Borne looked up eagerly.

"I wish you would," he begged, "and bring your step-daughter. You can't imagine," he added, with a glance at the girl who was sitting at his left hand, "how much pleasure it would give me. The roads are really not bad, and every one admits that the country is delightful."

"You had better be careful," the Princess said, "or we may take you at your word. I warn you, though, that it would be a regular invasion. Major Forrest and Lord Ronald are talking about coming with us."

"It's just an idea," Forrest remarked carelessly. "I wouldn't mind it myself, but I don't fancy we should get Engleton away from town before Goodwood."

"Well, I like that," Engleton remarked. "Forrest's a lot keener on these social functions than I am. As a matter of fact I am for the tour, on one condition."

"And that?" the Princess asked.

"That you come in my car," Lord Ronald answered. "I haven't really had a chance to try it yet, but it's a sixty horse Mercedes, and it's fitted up for touring. Take the lot of us easy, luggage and everything."

"I think it would be perfectly delightful," the Princess declared. "Do you really mean it?"

"Of course I do," Lord Ronald answered. "It's too hot for town, and I'm rather great on rusticating, myself."

"I think this is charming," the Princess declared. "Here we have one of our friends with a car and another with a house. But seriously, Cecil, we mustn't think of coming to you. There would be too many of us."

"The more the better," Cecil said eagerly. "If you really want to attempt anything in the shape of a rest-cure, I can recommend my home thoroughly. I am afraid," he added, with a shrug of the shoulders, "that I cannot recommend it for anything else."

"A rest," the Princess declared, "is exactly what we want. Life here is becoming altogether too strenuous. We started the season a little early. I am perfectly certain that we could not possibly last till the end. Until I arrived in London with an heiress under my charge, I had no idea that I was such a popular person."

The girl who was sitting on the other side of their host spoke almost for the first time. She was evidently quite young, and her pale cheeks, dark full eyes, and occasional gestures, indicated clearly enough something foreign in her nationality. She addressed no one in particular, but she looked toward Forrest.

"That is one of the things," she said, "which puzzles me. I do not understand it at all. It seems as though every one is liked or disliked, here in London at any rate, according to the amount of money they have."

"Upon my word, Miss Jeanne, it isn't so with every one," Lord Ronald interposed hastily.

She glanced at him indifferently.

"There may be exceptions," she said. "I am speaking of the great number."

"For Heaven's sake, child, don't be cynical!" the Princess remarked. "There is no worse pose for a child of your age."

"It is not a pose at all," Jeanne answered calmly. "I do not want to be cynical, and I do not want to have unkind thoughts. But tell me, Lord Ronald, honestly, do you think that every one would have been as kind to a girl just out of boarding-school as they have been to me if it were not that I have so much money?"

"I cannot tell about others," Lord Ronald answered. "I can only answer for myself."

His last words were almost whispered in the girl's ears, but she only shrugged her shoulders and did not return his gaze. Their host, who had been watching them, frowned slightly. He was beginning to think that Engleton was scarcely as pleasant a fellow as he had thought him.

"Well," he said, "Miss Le Mesurier will find out in time who are really her friends."

"It is a safe plan," Major Forrest remarked, "and a pleasant one, to believe in everybody until they want something from you. Then is the time for distrust."

Jeanne sighed.

"And by that time, perhaps," she said, "one's affections are hopelessly engaged. I think that it is a very difficult world."

The Princess shrugged her shoulders.

"Three months," she remarked, "is not a long time. Wait, my dear child, until you have at least lived through a single season before you commit yourself to any final opinions."

Their host intervened. He was beginning to find the conversation dull. He was far more interested in another matter.

"Let us talk about that visit," he said to the Princess. "I do wish that you could make up your mind to come. Of course, I haven't any amusements to offer you, but you could rest as thoroughly as you like. They say that the air is the finest in England. There is always bridge, you know, for the evenings, and if Miss Jeanne likes bathing, my gardens go down to the beach."

"It sounds delightful," the Princess said, "and exactly what we want. We have a good many invitations, but I have not cared to accept any of them, for I do not think that Jeanne would care much for the life at an ordinary country house. I myself," she continued, with perfect truth, "am not squeamish, but the last house-party I was at was certainly not the place for a very young girl."

"Make up your mind, then, and say yes," Cecil de la Borne pleaded.

"You shall hear from us within the next few days," the Princess answered. "I really believe that we shall come."

The little party left the restaurant a few minutes later on their way into the foyer for coffee. The Princess contrived to pass out with Forrest as her companion.

"I think," she said under her breath, "that this is the best opportunity you could possibly have. We shall be quite alone down there, and perhaps it would be as well that you were out of London for a few weeks. If it does not come to anything we can easily make an excuse to get away."

Forrest nodded.

"But who is this young man, De la Borne?" he asked. "I don't mean that. I know who he is, of course, but why should he invite perfect strangers to stay with him?"

The Princess smiled faintly.

"Can't you see," she answered, "that he is simply a silly boy? He is only twenty-four years old, and I think that he cannot have seen much of the world. He told me that he had just been abroad for the first time. He fancies that he is a little in love with me, and he is dazzled, of course, by the idea of Jeanne's fortune. He wants to play the host to us. Let him. I should be glad enough to get away for a few weeks, if only to escape from these pestering letters. I do think that one's tradespeople might let one alone until the end of the season."

Forrest, who was feeling a good deal braver since dinner, on the whole favoured the idea.

"I do not see," he remarked, "why it should not work out very well indeed. There will be nothing to do in the evenings except to play bridge, and no one to interfere."

"Besides which," the Princess remarked, "you will be out of London for a few weeks, and I dare say that if you keep away from the clubs for a time and lose a few rubbers when you get back your little trouble may blow over."

"I suppose," Forrest remarked thoughtfully, "this young De la Borne has no people living with him, guardians, or that sort of thing?"

"No one of any account," the Princess answered. "His father and mother are both dead. I am afraid, though, he will not be of any use to you, for from what I can hear he is quite poor. However, Engleton ought to be quite enough if we can keep him in the humour for playing."

"Ask him a few more questions about the place," Forrest said. "If it seems all right, I should like to start as soon as possible."

They had their coffee at a little table in the foyer, which was already crowded with people. Their conversation was often interrupted by the salutations of passing acquaintances. Jeanne alone looked about her with any interest. To the others, this sort of thing—the music of the red-coated band, the flowers, and the passing throngs of people, the handsomest and the weariest crowd in the world—were only part of the treadmill of life.

"By the by, Mr. De la Borne," the Princess asked, "how much longer are you going to stay in London?"

"I must go back to-morrow or the next day," the young man answered, a little gloomily. "I sha'n't mind it half so much if you people only make up your minds to pay me that visit."

The Princess motioned to him to draw his chair a little nearer to hers.

"If we take this tour at all," she remarked, "I should like to start the day after to-morrow. There is a perfectly hideous function on Thursday which I should so like to miss, and the stupidest dinner-party on earth at night. Should you be home by then, do you think?"

"If there were any chance of your coming at all," the young man answered eagerly, "I should leave by the first train to-morrow morning."

"I think," the Princess declared softly, "that we will come. Don't think me rude if I say that we could not possibly be more bored than we are in London. I do not want to take Jeanne to any of the country house-parties we have been invited to. You know why. She really is such a child, and I am afraid that if she gets any wrong ideas about things she may want to go back to the convent. She has hinted at it more than once already."

"There will be nothing of that sort at Salt-house," Cecil de la Borne declared eagerly. "You see, I sha'n't have any guests at all except just yourselves. Don't you think that would be best?"

"I do, indeed," the Princess assented, "and mind, you are not to make any special preparations for us. For my part, I simply want a little rest before we go abroad again, and we really want to come to you feeling the same way that one leaves one's home for lodgings in a farmhouse. You will understand this, won't you, Cecil?" she added earnestly, laying her fingers upon his arm, "or we shall not come."

"It shall be just as you say," he answered. "As a matter of fact the Red Hall is little more than a large farmhouse, and there is very little preparation which I could make for you in a day or a day and a half. You shall come and see how a poor English countryman lives, whose lands and income have shrivelled up together. If you are dull you will not blame me, I know, for all that you have to do is to go away."

The Princess rose and put out her hand.

"It is settled, then," she declared. "Thank you, dear Mr. Host, for your very delightful dinner. Jeanne and I have to go on to Harlingham House for an hour or two, the last of these terrible entertainments, I am glad to say. Do send me a note round in the morning, with the exact name of your house, and some idea of the road we must follow, so that we do not get lost. I suppose you two," she added, turning to Forrest and Lord Ronald, "will not mind starting a day or two before we had planned?"

"Not in the least," they assured her.

"And Miss Le Mesurier?" Cecil de la Borne asked. "Will she really not mind giving up some of these wonderful entertainments?"

Jeanne smiled upon him brilliantly. It was a smile which came so seldom, and which, when it did come, transformed her face so utterly, that she seemed like a different person.

"I shall be very glad, indeed," she said, "to leave London. I am looking forward so much to seeing what the English country is like."

"It will make me very happy," Cecil de la Borne said, bowing over her hand, "to try and show you."

Her eyes seemed to pass through him, to look out of the crowded room, as though indeed they had found their way into some corner of the world where the things which make life lie. It was a lapse from which she recovered almost immediately, but when she looked at him, and with a little farewell nod withdrew her hand, the transforming gleam had passed away.

"And there is the sea, too," she remarked, looking backwards as they passed out. "I am longing to see that again."

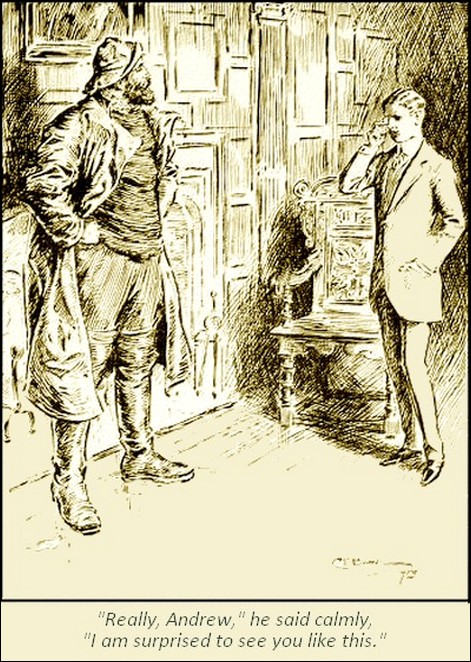

Perhaps there was never a moment in the lives of these two men when their utter and radical dissimilarity, physically as well as in the larger ways, was more strikingly and absolutely manifest. Like a great sea animal, huge, black-bearded, bronzed, magnificent, but uncouth, Andrew de la Borne, in the oilskins and overalls of a village fisherman, stood in the great bare hall in front of the open fireplace, reckless of his drippings, at first only mildly amused by the half cynical, half angry survey of the very elegant young man who had just descended the splendid oak staircase, with its finely carved balustrade, black and worm-eaten, Cecil de la Borne stared at his brother with the angry disgust of one whose sense of all that is holiest stands outraged. Slim, of graceful though somewhat undersized figure, he was conscious of having attained perfection in matters which he reckoned of no small importance. His grey tweed suit fitted him like a glove, his tie was a perfect blend between the colour of his eyes and his clothes, his shoes were of immaculate shape and polish, his socks had been selected with care in the Rue de la Paix. His hair was brushed until it shone with the proper amount of polish, his nails were perfectly manicured, even his cigarette came from the dealer whose wares were the caprice of the moment. That his complexion was pallid and that underneath his eyes were faint blue lines, which were certainly not the hall-marks of robust health, disturbed him not at all. These things were correct. Health was by no means a desideratum in the set to which he was striving to belong. He looked through his eyeglass at his brother and groaned.

"Really, Andrew," he said calmly, but with an undernote of anger trembling in his tone, "I am surprised to see you like this! You might, I think, have had a little more consideration. Can't you realize what a sight you are, and what a mess you're making!"

Andrew took off his cap and shook it, so that a little shower of salt water splashed on to the polished floor.

"Never mind, Cecil," he said good-humouredly. "You've all the deportment that's necessary in this family. And salt water doesn't stain. These boards have been washed with it many a time."

The young man's face lost none of his irritation.

"But what on earth have you been doing?" he exclaimed. "Where have you been to get in a state like that?"

Andrew's face was suddenly overcast. It did not please him to think of those last few hours.

"I had to go out to bring a mad woman home," he said. "Kate Caynsard was out in her catboat a day like this. It was suicide if I hadn't reached her in time."

"You—did reach her in time?" the young man asked quickly.

Andrew turned to face the questioner, and the eyes of the brothers met. Again the differences between them seemed to be suddenly and marvellously accentuated. Andrew's cheeks, bronzed and hardened with a life spent wholly out of doors, were glistening still with the salt water which dripped down from his hair and hung in sparkling globules from his beard. Cecil was paler than ever; there was something almost furtive in that swift insistent look. Perhaps he recognized something of what was in the other's mind. At any rate the good-nature left his manner—his tone took to itself a sterner note.

"I came back," he said grimly. "I should not have come back alone. She was hard to save, too," he added, after a moment's pause.

"She is mad," Cecil muttered. "A queer lot, all the Caynsards."

"She is as sane as you or I," his brother answered. "She does rash things, and she chooses to treat her life as though it were a matter of no consequence. She took a fifty to one chance at the bar, and she nearly lost. But, by heaven, you should have seen her bring my little boat down the creek, with the tide swelling, and a squall right down on the top of us. It was magnificent. Cecil!"

"Well?"

"Why does Kate Caynsard treat her life as though it were of less value than the mackerel she lowers her line for? Do you know?"

The younger man dropped his eyeglass and shrugged his shoulders contemptuously.

"Since when," he demanded, "have I shown any inclination to play the village Lothario? Thick ankles and robust health have never appealed to me—I prefer the sicklier graces of civilization."

"Kate Caynsard," Andrew said thoughtfully, "is not of the villagers. She leads their life, but her birth is better on her father's side, at any rate, than our own."

"If I might be allowed to make the suggestion," Cecil said, regarding his brother with supercilious distaste, "don't you think it would be just as well to change your clothes before our guests arrive?"

"Why should I?" Andrea asked calmly.

"They are not my friends. I scarcely know even their names. I entertain them at your request. Why should I be ashamed of my oilskins? They are in accord with the life I live here. I make no pretence, you see, Cecil," he added, with a faintly amused smile, "at being an ornamental member of Society."

His brother regarded him with something very much like disgust.

"No!" he said sarcastically. "No one could accuse you of that."

Something in his tone seemed to suggest to Andrew a new idea. He looked down at the clothes he wore beneath his oilskins—the clothes almost of a working man. He glanced for a moment at his hands, hardened and blistered with the actual toil which he loved—and he looked his brother straight in the face.

"Cecil," he said, "I believe you're ashamed of me."

"Of course I am," the younger man answered brutally. "It's your own fault. You choose to make a fisherman or a labouring man of yourself. I haven't seen you in a decent suit of clothes for years. You won't dress for dinner. Your hands and skin are like a ploughboy's. And, d—n it all, you're my elder brother! I've got to introduce you to my friends as the head of the De la Bornes, and practically their host. No wonder I don't like it!"

There was a moment's silence. If his words hurt, Andrew made no sign. With a shrug of the shoulders he turned towards the staircase.

"There is no reason," he remarked, carelessly enough, "why I should inflict the humiliation of my presence on you or on your friends. I am going down to the Island. You shall entertain your friends and play the host to your heart's content. It will be more comfortable for both of us."

Cecil prided himself upon a certain impassivity of features and manner which some fin de siecle oracle of the cities had pronounced good form, but he was not wholly able to conceal his relief. Such an arrangement was entirely to his liking. It solved the situation satisfactorily in more ways than one.

"It's a thundering good idea, Andrew, if you're sure you'll be comfortable there," he declared. "I don't believe you would get on with my friends a bit. They're not your sort. Seems like turning you out of your own house, though."

"It is of no consequence," Andrew said coldly. "I shall be perfectly comfortable."

"You see," Cecil continued, "they're not keen on sport at all, and you don't play bridge—"

Andrew had already disappeared. Cecil turned back into the hall and lit a cigarette.

"Phew! What a relief!" he muttered to himself. "If only he has the sense to keep away all the time!"

He rang the bell, which was answered by a butler newly imported from town.

"Clear away all this mess, James," Cecil ordered, pointing in disgust to the wet places upon the floor, and the still dripping southwester, "and serve tea here in an hour, or directly my friends arrive—tea, and whisky and soda, and liqueurs, you know, with sandwiches and things."

"I will do my best, sir," the man answered. "The kitchen arrangements are a little—behind the times, if I might venture to say so."

"I know, I know," Cecil answered irritably. "The place has been allowed to go on anyhow while I was away. Do what you can, and let them know outside that they must make room for one, or perhaps two automobiles...."

Upstairs Andrew was rapidly throwing a few things together. With an odd little laugh he threw into the bottom of a wardrobe an unopened parcel of new clothes and a dress suit which had been carefully brushed. In less than twenty minutes he had left the house by the back way, with a small portmanteau poised easily upon his massive shoulders. As he turned from the long ill-kept avenue, with its straggling wind-smitten trees all exposed to the tearing ocean gales, into the high road, a great automobile swung round the corner and slackened speed. Major Forrest leaned out and addressed him.

"Can you tell me if this is the Red Hall, my man—Mr. De la Borne's place?" he asked.

Andrew nodded, without a glance at the veiled and shrouded women who were leaning forward to hear his answer.

"The next avenue is the front way," he said. "Mind how you turn in—the corner is rather sharp."

He spoke purposely in broad Norfolk, and passed on.

"What a Goliath!" Engleton remarked.

"I should like to sketch him," the Princess drawled. "His shoulders were magnificent."

But neither of them had any idea that they had spoken with the owner of the Red Hall.

About half-way through dinner that night, Cecil de la Borne drew a long sigh of relief. At last his misgivings were set at rest. His party was going to be, was already, in fact, pronounced, a success. A glance at his fair neighbour, however, who was lighting her third or fourth Russian cigarette since the caviare, sent a shiver of thankfulness through his whole being. What a sensible fellow Andrew had been to clear out. This sort of thing would not have appealed to him at all.

"My dear Cecil," the Princess declared, "I call this perfectly delightful. Jeanne and I have wanted so much to see you in your own home. Jeanne, isn't this nicer, ever so much nicer, than anything you had imagined?"

Jeanne, who was sitting opposite, lifted her remarkable eyes and glanced around with interest.

"Yes," she admitted, "I think that it is! But then, any place that looks in the least like a home is a delightful change after all that rushing about in London."

"I agree with you entirely," Major Forrest declared. "If our friend has disappointed us at all, it is in the absence of that primitiveness which he led us to expect. One perceives that one is drinking Veuve Clicquot of a vintage year, and one suspects the nationality of our host's cook."

"You can have all the primitivism you want if you look out of the windows," Cecil remarked drily. "You will see nothing but a line of stunted trees, and behind, miles of marshes and the greyest sea which ever played upon the land. Listen! You don't hear a sound like that in the cities."

Even as he spoke they heard the dull roar of the north wind booming across the wild empty places which lay between the Red Hall and the sea. A storm of raindrops was flung against the window. The Princess shivered.

"It is an idyll, the last word in the refining of sensations," Major Forrest declared. "You give us sybaritic luxury, and in order that we shall realize it, you provide the background of savagery. In the Carlton one might dine like this and accept it as a matter of course. Appreciation is forced upon us by these suggestions of the wilderness without."

"Not all without, either," Cecil de la Borne remarked, raising his eyeglass and pointing to the walls. "See where my ancestors frown down upon us—you can only just distinguish their bare shapes. No De la Borne has had money enough to have them renovated or even preserved. They have eaten their way into the canvases, and the canvases into the very walls. You see the empty spaces, too. A Reynolds and a Gainsboro' have been cut out from there and sold. I can show you long empty galleries, pictureless, and without a scrap of furniture. We have ghosts like rats, rooms where the curtains and tapestries are falling to pieces from sheer decay. Oh! I can assure you that our primitivism is not wholly external."

He turned from the Princess, who was not greatly interested, to find that for once he had succeeded in riveting the attention of the girl, whose general attitude towards him and the whole world seemed to be one of barely tolerant indifference.

"I should like to see over your house, Mr. De la Borne," she said. "It all sounds very interesting."

"I am afraid," he answered, "that your interest would not survive very long. We have no treasures left, nor anything worth looking at. For generations the De la Bornes have stripped their house and sold their lands to hold their own in the world. I am the last of my race, and there is nothing left for me to sell," he declared, with a momentary bitterness.

"Hadn't you—a half brother?" the Princess asked.

Cecil hesitated for a moment. He had drifted so easily into the position of head of the house. It was so natural. He felt that he filled the place so perfectly.

"I have," he admitted, "but he counts, I am sorry to say, for very little. You are never likely to come across him—nor any other civilized person."

There was a subtle indication in his tone of a desire not to pursue the subject. His guests naturally respected it. There was a moment's silence. Then Cecil once more leaned forward. He hesitated for a moment, even after his lips had parted, as though for some reason he were inclined, after all, to remain silent, but the consciousness that every one was looking at him and expecting him to speak induced him to continue with what, after all, he had suddenly, and for no explicit reason, hesitated to say.

"You spoke, Miss Le Mesurier," he began, "of looking over the house, and, as I told you, there is very little in it worth seeing. And yet I can show you something, not in the house itself, but connected with it, which you might find interesting."

The Princess leaned forward in her chair.

"This sounds so interesting," she murmured. "What is it, Cecil? A haunted chamber?"

Their host shook his head.

"Something far more tangible," he answered, "although in its way quite as remarkable. Hundreds of years ago, smuggling on this coast was not only a means of livelihood for the poor, but the diversion of the rich. I had an ancestor who became very notorious. His name seems to have been a by-word, although he was never caught, or if he was caught, never punished. He built a subterranean way underneath the grounds, leading from the house right to the mouth of one of the creeks. The passage still exists, with great cellars for storing smuggled goods, and a room where the smugglers used to meet."

Jeanne looked at him with parted lips.

"You can show me this?" she asked, "the passage and the cellars?"

Cecil nodded.

"I can," he answered. "Quite a weird place it is, too. The walls are damp, and the cellars themselves are like the vaults of a cathedral. All the time at high tide you can hear the sea thundering over your head. To-morrow, if you like, we will get torches and explore them."

"I should love to," Jeanne declared. "Can you get out now at the other end?"

Cecil nodded.

"The passage," he said, "starts from a room which was once the library, and ends half-way up the only little piece of cliff there is. It is about thirty feet from the ground, but they had a sort of apparatus for pulling up the barrels, and a rope ladder for the men. The preventive officers would see the boat come up the creek, and would march down from the village, only to find it empty. Of course, they suspected all the time where the things went, but they could not prove it, and as my ancestor was a magistrate and an important man they did not dare to search the house."

The Princess sighed gently.

"Those were the days," she murmured, "in which it must have been worth while to live. Things happened then. To-day your ancestor would simply have been called a thief."

"As a matter of fact," Cecil remarked, "I do not think that he himself benefited a penny by any of his exploits. It was simply the love of adventure which led him into it."

"Even if he did," Major Forrest remarked, "that same predatory instinct is alive to-day in another guise. The whole world is preying upon one another. We are thieves, all of us, to the tips of our finger-nails, only our roguery is conducted with due regard to the law."

The Princess smiled faintly as she glanced across the table at the speaker.

"I am afraid," she said, with a little sigh, "that you are right. I do not think that we have really improved with the centuries. My own ancestors sacked towns and held the inhabitants to ransom. To-day I sit down to bridge opposite a man with a well-filled purse, and my one idea is to lighten it. Nothing, I am convinced, but the fear of being found out, keeps us reasonably moral."

"If we go on talking like this," Lord Ronald remarked, "we shall make Miss Le Mesurier nervous. She will feel that we, and the whole of the rest of the world, have our eyes upon her moneybags."

"I am absolutely safe," Jeanne answered smiling. "I do not play bridge, and even my signature would be of no use to any one yet."

"But you might imagine us," Lord Ronald continued, "waiting around breathlessly until the happy time arrived when you were of age, and we could pursue our diabolical schemes."

Jeanne shook her head.

"You cannot frighten me, Lord Ronald," she said. "I feel safe from every one. I am only longing for to-morrow, for a chance to explore this wonderful subterranean passage."

"I am afraid," their host remarked, "that you will be disappointed. With the passing of smuggling, the romance of the thing seems to have died. There is nothing now to look at but mouldy walls, a bare room, and any amount of the most hideous fungi. I can promise you that when you have been there for a few minutes your only desire will be to escape."

"I am not so sure," the girl answered. "I think that associations always have an effect on me. I can imagine how one might wait there, near the entrance, hear the soft swish of the oars, look down and see the smugglers, hear perhaps the muffled tramp of men marching from the village. Fancy how breathless it must have been, the excitement, the fear of being caught."

Cecil curled his slight moustache dubiously.

"If you can feel all that in my little bit of underground world," he said, "I shall think that you are even a more wonderful person—"

He dropped his voice and leaned toward her, but Jeanne laughed in his face and interrupted him.

"People who own things," she remarked, "never look upon them with proper reverence. Don't you see that my mother is dying for some bridge?"

The Princess was only obeying a faint sign from Forrest. She leaned forward and addressed her host.

"It isn't a bad idea," she declared. "Where are we going to play bridge, Cecil? In some smaller room, I hope. This one is really beginning to get on my nerves a little. There is an ancestor exactly opposite who has fixed me with a luminous and a disapproving eye. And the blank spaces on the wall! Ugh! I feel like a Goth. We are too modern for this place, Cecil."

Their host laughed as he rose and turned towards Jeanne.

"Your mother," he said, "is beginning to be conscious of her environment. I know exactly how she is feeling, for I myself am a constant sufferer. Are you, too, sighing for the gilded salons of civilization?"

"Not in the least," Jeanne answered frankly. "I am tired of mirrors and electric lights and babble. I prefer our present surroundings, and I should not mind at all if some of those disapproving ancestors of yours stepped out of their frames and took their places with us here."

Cecil laughed.

"If they have been listening to our conversation," he said, "I think that they will stay where they are. Like royalty," he continued, "we can boast an octagonal chamber. I fear that its glories are of the past, but it is at least small, and the wallpaper is modern. I have ordered coffee and the card-tables there. Shall we go?"

He led the way out of the gloomy room, chilly and bare, yet in a way magnificent still with its reminiscences of past splendour, across the hall, modernized with rugs and recent furnishing, into a smaller apartment, where cheerfulness reigned. A wood fire burnt in an open grate. Lamps and a fine candelabrum gave a sufficiency of light. The furniture, though old, was graceful, and of French design. It had been the sitting chamber of the ladies of the De la Borne family for generations, and it bore traces of its gentler occupation. One thing alone remained of primevalism to remind them of their closer contact with the great forces of nature. The chamber was built in the tower, which stood exposed to the sea, and the roar of the wind was ceaseless.

"Here at least we shall be comfortable, I think," Cecil remarked, as they all entered. "My frescoes are faded, but they represent flowers, not faces. There are no eyes to stare at you from out of the walls here, Princess."

The Princess laughed gaily as she seated herself before a Louis Quinze card-table, and threw a pack of cards across the faded green baize cloth.

"It is charming, this," she declared. "Shall we challenge these two boys, Nigel? You are the only man who understands my leads, and who does not scold me for my declarations."

"I am perfectly willing," Forrest answered smoothly. "Shall we cut for deal?"

Cecil de la Borne leaned over and turned up a card.

"I am quite content," he remarked. "What do you say, Engleton?"

Engleton hesitated for a moment. The Princess turned and looked at him. He was standing upon the hearthrug smoking, his face as expressionless as ever.

"Let us cut for partners," he drawled. "I am afraid of the Princess and Forrest. The last time I found them a quite invincible couple."

There was a moment's silence. The Princess glanced toward Forrest, who only shrugged his shoulders.

"Just as you will," he answered.

He turned up an ace and the Princess a three.

"After all," he remarked, with a smile, "it seems as though fate were going to link us together."

"I am not so sure," Cecil de la Borne said, also throwing down an ace. "It depends now upon Engleton."

Engleton came to the table, and drew a card at random from the pack. Forrest's eyes seemed to narrow a little as he looked down at it. Engleton had drawn another ace.

"Forrest and I," he remarked. "Jolly low cutting, too. I have played against you often, Forrest, but I think this is our first rubber together. Here's good luck to us!"

He tossed off his liqueur and sat down. They cut again for deal, and the game proceeded.

Jeanne had moved across towards the window, and laid her fingers upon the heavy curtains. Cecil de la Borne, who was dummy, got up and stood by her side.

"Do you know," she said, "although your frescoes are flowers, I feel that there are eyes in this room, too, only that they are looking in from the night. Can one see the sea from here, Mr. De la Borne?"

"It is scarcely a hundred yards away," he answered. "This window looks straight across the German Ocean, and if you look long enough you will see the white of the breakers. Listen! You will hear, too, what my forefathers, and those who begat them, have heard, from the birth of the generations."

The girl, with strained face, stood looking out into the darkness. Outside, the wind and sea imposed their thunder upon the land. Within, there was no sound but the softer patter of the cards, the languid voices of the four who played bridge. A curious little company, on the whole. The Princess of Strurm, whose birth was as sure as her social standing was doubtful, the heroine of countless scandals, ignored by the great heads of her family, impoverished, living no one knew how, yet remaining the legal guardian of a stepdaughter, who was reputed to be one of the greatest heiresses in Europe. The courts had moved to have her set aside, and failed. A Cardinal of her late husband's faith, empowered to treat with her on behalf of his relations, offered a fortune for her cession of Jeanne, and was laughed at for his pains. Whatever her life had been, she remained custodian of the child of the great banker whom she had married late in life. She endured calmly the threats, the entreaties, the bribes, of Jeanne's own relations. Jeanne, she was determined, should enter life under her wing, and hers only. In the end she had her way. Jeanne was entering life now, not through the respectable but somewhat bourgeois avenue by which her great monied relatives would have led her, but under the auspices of her stepmother, whose position as chaperon to a great heiress had already thrown open a great many doors which would have been permanently closed to her in any other guise. The Princess herself was always consistent. She assumed to herself an arrogant right to do as she pleased and live as she pleased. She was of the House of Strurm, which had been noble for centuries, and had connections with royalty. That was enough. A few forgot her past and admitted her claim. Those who did not she ignored....

Then there was Lord Ronald Engleton, an orphan brought up in Paris, a would-be decadent, a dabbler in all modern iniquities, redeemed from folly only by a certain not altogether wholesome cleverness, yet with a disposition which sometimes gained for him friends in most unlikely quarters. He had excellent qualities, which he did his best to conceal; impulses which he was continually stifling.

By his side sat Forrest, the Sphynx, more than middle-aged, a man who had wandered all over the world, who had tried many things without ever achieving prosperity, and who was searching always, with tired eyes, for some new method of clothing and feeding himself upon an income of less than nothing a year. He had met the Princess at Marienbad years ago, and silently took his place in her suite. Why, no one seemed to know, not even at first the Princess herself, who thought him chic, and adored what she could not understand. Curious flotsam and jetsam, these four, of society which had something of a Continental flavour; personages, every one of them, with claim to recognition, but without any noticeable hall-mark....

There remained the girl, Jeanne herself, half behind the curtain now, her head thrust forward, her beautiful eyes contracted with the effort to penetrate that veil of darkness. One gift at least she seemed to have borrowed from the woman who gambled with life as easily and readily as with the cards which fell from her jewelled fingers. In her face, although it was still the face of a child, there was the same inscrutable expression, the same calm languor of one who takes and receives what life offers with the indifference of the cynic, or the imperturbability of the philosopher. There was little of the joy or the anticipation of youth there, and yet, behind the eyes, as they looked out into the darkness, there was something—some such effort, perhaps, as one seeking to penetrate the darkness of life must needs show. And as she looked, the white, living breakers gradually resolved them-selves out of the dark, thin filmy phosphorescence, and the roar of the lashed sea broke like thunder upon the pebbled beach. She leaned a little more forward, carried away with her fancy—that the shrill grinding of the pebbles was indeed the scream of human voices in pain!

With the coming of dawn the storm passed away northwards, across a sea snow-flecked and still panting with its fury, and leaving behind many traces of its violence, even upon these waste and empty places. A lurid sunrise gave little promise of better weather, but by six o'clock the wind had fallen, and the full tide was swelling the creeks. On a sand-bank, far down amongst the marshes, Jeanne stood hatless, with her hair streaming in the breeze, her face turned seaward, her eyes full of an unexpected joy. Everywhere she saw traces of the havoc wrought in the night. The tall rushes lay broken and prostrate upon the ground; the beach was strewn with timber from the breaking up of an ancient wreck. Eyes more accustomed than hers to the outline of the country could have seen inland dismantled cottages and unroofed sheds, groups of still frightened and restive cattle, a snapped flagstaff, a fallen tree. But Jeanne knew none of these things. Her face was turned towards the ocean and the rising sun. She felt the sting of the sea wind upon her cheeks, all the nameless exhilaration of the early morning sweetness. Far out seaward the long breakers, snow-flecked and white crested, came rolling in with a long, monotonous murmur toward the land. Above, the grey sky was changing into blue. Almost directly over her head, rising higher and higher in little circles, a lark was singing. Jeanne half closed her eyes and stood still, engrossed by the unexpected beauty of her surroundings. Then suddenly a voice came travelling to her from across the marshes.

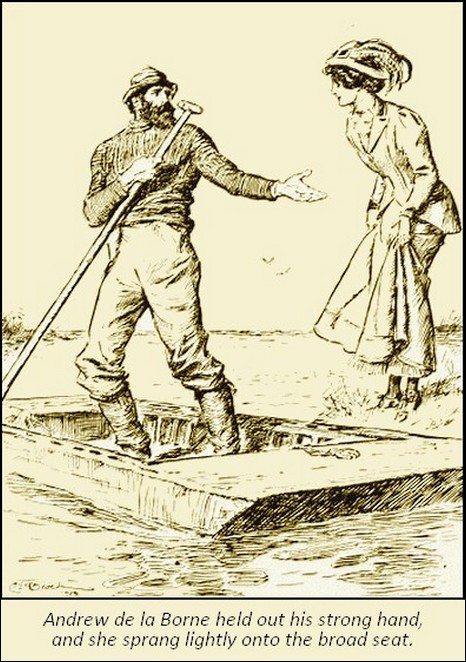

She turned round unwillingly, and with a vague feeling of irritation against this interruption, which seemed to her so inopportune, and in turning round she realized at once that her period of absorption must have lasted a good deal longer than she had had any idea of. She had walked straight across the marshes towards the little hillock on which she stood, but the way by which she had come was no longer visible. The swelling tide had circled round through some unseen channel, and was creeping now into the land by many creeks and narrow ways. She herself was upon an island, cut off from the dry land by a smoothly flowing tidal way more than twenty yards across. Along it a man in a flat-bottomed boat was punting his way towards her. She stood and waited for him, admiring his height, and the long powerful strokes with which he propelled his clumsy craft. He was very tall, and against the flat background his height seemed almost abnormal. As soon as he had attracted her attention he ceased to shout, and devoted all his attention to reaching her quickly. Nevertheless, the salt water was within a few feet of her when he drove his pole into the bottom, and brought the punt to a momentary standstill. She looked down at him, smiling.

"Shall I get in?" she asked.

"Unless you are thinking of swimming back," he answered drily, "it would be as well."

She lifted her skirts a little, and laughed at the inappropriateness of her thin shoes and open-work stockings. Andrew de la Borne held out his strong hand, and she sprang lightly on to the broad seat.

"It is very nice of you," she said, with her slight foreign accent, "to come and fetch me. Should I have been drowned?"

"No!" he answered. "As a matter of fact, the spot where you were standing is not often altogether submerged. You might have been a prisoner for a few hours. Perhaps as the tide is going to be high, your feet would have been wet. But there was no danger."

She settled down as comfortably as possible in the awkward seat.

"After all, then," she said, "this is not a real adventure. Where are you going to take me to?"

"I can only take you," he answered, "to the village. I suppose you came from the Hall?"

"Yes!" she answered. "I walked straight across from the gate. I never thought about the tide coming up here."

"You will have to walk back by the road," he answered. "It is a good deal further round, but there is no other way."

She hung her hand over the side, rejoicing in the touch of the cool soft water.

"That," she answered, "does not matter at all. It is very early still, and I do not fancy that any one will be up yet for several hours."

He made no further attempt at conversation, devoting himself entirely to the task of steering and propelling his clumsy craft along the narrow way. She found herself watching him with some curiosity. It had never occurred to her to doubt at first but that he was some fisherman from the village, for he wore a rough jersey and a pair of trousers tucked into sea-boots. His face was bronzed, and his hands were large and brown. Nevertheless she saw that his features were good, and his voice, though he spoke the dialect of the country, had about it some quality which she was not slow to recognize.

"Who are you?" she asked, a little curiously. "Do you live in the village?"

He looked down at her with a faint smile.

"I live in the village," he answered, "and my name is Andrew."

"Are you a fisherman?" she asked.

"Certainly," he answered gravely. "We are all fishermen here."

She was not altogether satisfied. He spoke to her easily, and without any sort of embarrassment. His words were civil enough, and yet he had more the air of one addressing an equal than a villager who is able to be of service to some one in an altogether different social sphere.

"It was very fortunate for me," she said, "that you saw me. Are you up at this hour every morning?"

"Generally," he answered. "I was thinking of fishing, higher up in the reaches there."

"I am sorry," she said, "that I spoiled your sport."

He did not answer at once. He, in his turn, was looking at her. In her tailor-made gown, short and fashionably cut, her silk stockings and high-heeled shoes, she certainly seemed far indeed removed from any of the women of those parts. Her dark hair was arranged after a fashion that was strange to him. Her delicately pale skin, her deep grey eyes, and unusually scarlet lips were all indications of her foreign extraction. He looked at her long and searchingly. This was the girl, then, whom his brother was hoping to marry.

"You are not English," he remarked, a little abruptly.

She shook her head.

"My father was a Portuguese," she said, "and my mother French. I was born in England, though. You, I suppose, have lived here all your life?"

"All my life," he repeated. "We villagers, you see, have not much opportunity for travel."

"But I am not sure," she said, looking at him a little doubtfully, "that you are a villager."

"I can assure you," he answered, "that there is no doubt whatever about it. Can you see out yonder a little house on the island there?"

She followed his outstretched finger.

"Of course I can," she answered. "Is that your home?"

He nodded.

"I am there most of my time," he answered.

"It looks charming," she said, a little doubtfully, "but isn't it lonely?"

He shrugged his shoulders.

"Perhaps," he answered. "I am only ten minutes' sail from the mainland, though."

She looked again at the house, long and low, with its plaster walls bare of any creeping thing.

"It must be rather fascinating," she admitted, "to live upon an island. Are you married?"

"No!" he answered.

"Do you mean that you live quite alone?" she asked.

He smiled down upon her as one might smile at an inquisitive child. "I have a ser—some one to look after me," he said. "Except for that I am quite alone. I am going to set you ashore here. You see those telegraph posts? That is the road which leads direct to the Hall."

She was still looking at the island, watching the waves break against a little stretch of pebbly beach.

"I should like very much," she said, "to see that house. Can you not take me out there?"

He shook his head.

"We could not get so far in this punt," he said, "and my sailing boat is up at the village quay, more than a mile away."

She frowned a little. She was not used to having any request of hers disregarded.

"Could we not go to the village," she asked, "and change into your boat?"

He shook his head.

"I am going fishing," he said, "in a different direction. Allow me."

He stepped on to land and lifted her out. She hesitated for a moment and felt for her purse.

"You must let me recompense you," she said coldly, "for the time you have lost in coming to my assistance."

He looked down at her, and again she had an uncomfortable sense that notwithstanding his rude clothes and country dialect, this man was no ordinary villager. He said nothing, however, until she produced her purse, and held out a little tentatively two half-crowns.

"You are very kind," he said. "I will take one if you will allow me. That is quite sufficient. You see the Hall behind the trees there. You cannot miss your way, I think, and if you will take my advice you will not wander about in the marshes here except at high tide. The sea comes in to the most unexpected places, and very quickly, too, sometimes. Good morning!"

"Good morning, and thank you very much," she answered, turning away toward the road.

Cecil de la Borne was standing at the end of the drive when she appeared, a telescope in his hand. He came hastily down the road to meet her, a very slim and elegant figure in his well-cut flannel clothes, smoothly brushed hair, and irreproachable tie.

"My dear Miss Jeanne," he exclaimed, "I have only just heard that you were out. Do you generally get up in the middle of the night?"

She smiled a little half-heartedly. It was curious that she found herself contrasting for a moment this very elegant young man with her roughly dressed companion of a few minutes ago.

"To meet with an adventure such as I have had," she answered, "I would never go to bed at all. I have been nearly drowned, and rescued by a most marvellous person. He brought me back to safety in a flat-bottomed punt, and I am quite sure from the way he stared at them that he had never seen open-work stockings before."

"Are you in earnest?" Cecil asked doubtfully.

"Absolutely," she answered. "I was walking there among the marshes, and I suddenly found myself surrounded by the sea. The tide had come up behind me without my noticing. A most mysterious person came to my rescue. He wore the clothes of a fisherman, and he accepted half a crown, but I have my doubts about him even now. He said that his name was Mr. Andrew."

Cecil opened the gate and they walked up towards the house. A slight frown had appeared upon his forehead.

"Do you know him?" she asked.

"I know who he is," he answered. "He is a queer sort of fellow, lives all alone, and is a bit cranky, they say. Come in and have some breakfast. I don't suppose that any one else will be down for ages."

She shook her head.

"I will send my woman down for some coffee," she answered. "I am going upstairs to change. I am just a little wet, and I must try and find some thicker shoes."

Cecil sighed.

"One sees so little of you," he murmured, "and I was looking forward to a tete-a-tete breakfast."

She shook her head as she left him in the hall.

"I couldn't think of it," she declared. "I'll appear with the others later on. Please find out all you can about Mr. Andrew and tell me."

Cecil turned away, and his face grew darker as he crossed the hall.

"If Andrew interferes this time," he muttered, "there will be trouble!"

The Princess appeared for luncheon and declared herself to be in a remarkably good humour.

"My dear Cecil," she said, helping herself to an ortolan in aspic, "I like your climate and I like your chef. I had my window open for at least ten minutes, and the sea air has given me quite an appetite. I have serious thoughts of embracing the simple life."

"You could scarcely," Cecil de la Borne answered, "come to a better place for your first essay. I will guarantee that life is sufficiently simple here for any one. I have no neighbours, no society to offer you, no distractions of any sort. Still, I warned you before you came."

"Don't be absurd," the Princess declared. "You have the sea almost at your front door, and I adore the sea. If you have a nice large boat I should like to go for a sail."

Cecil looked at her with upraised eyebrows.

"If you are serious," he said, "no doubt we can find the boat."

"I am absolutely serious," the Princess declared. "I feel that this is exactly what my system required. I should like to sit in a comfortable cushioned seat and sail somewhere. If possible, I should like you men to catch things from the side of the boat."

"You will get sunburnt," Lord Ronald remarked drily; "perhaps even freckled."

"Adorable!" the Princess declared. "A touch of sunburn would be quite becoming. It is such an excellent foundation to build a complexion upon. Jeanne is quite enchanted with the place. She's had adventures already, and been rescued from drowning by a marvellous person, who wore his trousers tucked into his boots and found fault with her shoes and stockings. She has promised to show me the place after luncheon, and I am going to stand there myself and see if anything happens."

"You will get your feet very wet," Cecil declared.

"And sand inside your shoes," Forrest remarked.

"These," the Princess declared, "are trifles compared with the delightful sensation of experiencing a real adventure. In any case we must sail one afternoon, Cecil. I insist upon it. We will not play bridge until after dinner. My luck last night was abominable. Oh, you needn't look at me like that," she added to Cecil. "I know I won, but that was an accident. I had bad cards all the time, and I only won because you others had worse. Please ring the bell, Mr. Host, and see about the boat."

"Really," Cecil remarked, as he called the butler and gave him some instructions, "I had no idea that I was going to entertain such enterprising guests."

"Oh, there are lots of things I mean to do!" the Princess declared. "I am seriously thinking of going shrimping. I suppose there are shrimps here, and I should love to tuck up my skirts and carry a big net, like somebody's picture."

"Perhaps," Cecil suggested, "you would like to try the golf links. I believe there are some quite decent ones not far away."

The Princess shook her head.

"No!" she answered. "Golf is too civilized a game. We will go out in a fishing boat with plenty of cushions, and we will try to catch fish. I know that Jeanne will love it, and that you others will hate it. Between the two of you it should be amusing."

"Very well," Cecil declared, with an air of resignation, "whatever happens will be upon your own shoulders. There is a boat in the village which we can have. I will have it brought up to our own quay in an hour's time. If the worst comes to the worst, and we are bored to death, we can play bridge on the way."

"There will be no cards upon the boat," the Princess declared decidedly. "I forbid them. We are going to lounge and look at the sea and get sunburnt. Jeanne can wear a veil if she likes. I shall not."

Cecil shrugged his shoulders.

"Very well," he said. "Whatever happens, don't blame me."

The Princess had her way and behaved like a schoolgirl. She sat in the most comfortable place, surrounded with a multitude of cushions, with her tiny Japanese spaniel in her arms, and a box of French bonbons by her side. Jeanne stood in the bows, bareheaded and happy. Lord Ronald, who was feeling a little sea-sick, sat at her feet.

"I had no idea," he remarked plaintively, "that your mother was capable of such crudities. If I had known, I certainly would not have trusted myself to such a party. This sea air is hateful. It has tarnished my cigarette-case already, and one's nails will not be fit to be seen. To be out of doors like this is worse than drinking unfiltered water."

Jeanne smiled down at him a little contemptuously.

"You are a child of the cities, Lord Ronald," she remarked. "Next year I am going to buy a yacht myself, but I shall not ask you to come with us."

Lord Ronald groaned.

"That is the worst of all heiresses," he said. "You have such queer tastes. I shall never summon up my courage to propose to you."

"There is always leap year," Jeanne reminded him.

"What a bewildering suggestion!" he murmured, looking uncomfortably over the side of the boat. "I say, Forrest, what do you think of this sort of thing?"

"Idyllic!" Forrest declared cynically. "To sit upon a hard plank and to have one's digestion unmercifully interfered with like this is unqualified rapture. If only there were cabins one might sleep."

"There will be cabins on my yacht," Jeanne declared laughing, "but I shall not ask either of you. You are both of you knights of the candle light. I shall get some great strong fisherman to be captain, and I shall go round the world and forget the days and the months."

Forrest shivered slightly.

"The country," he remarked to the Princess, "is having a terrible effect upon your stepdaughter."

The Princess nodded and thrust a bonbon into the languid jaws of the dog she was holding.

"It is my fault," she declared. "It is I who have set this fashion. It was a whim, and I am tired of it. Tell our host that we will go back."

They tacked a few minutes later, and swept shoreward. Jeanne, still standing in the bows, was gazing steadfastly upon the little island at the entrance of the estuary.

"I should like," she declared, pointing it out to Cecil, "to land there and have some tea."

Cecil looked at her doubtfully.

"We shall be home in a little more than an hour," he said, "and I don't suppose we could get any tea there, even if we were able to land."

"I have a conviction that we should," Jeanne declared. "Mother," she added, turning round to the older woman, "there is an island just ahead of us with a delightful looking cottage. I believe my preserver of this morning lives there. Wouldn't it be lovely to go and beg him to give us all tea?"

"Charming!" the Princess declared, sitting up amongst her cushions. "I should love to see him, and tea is the one thing in the world I want to make me happy."

Cecil de la Borne stood silent for a moment or two, looking steadfastly at the whitewashed cottage upon the island. It seemed impossible, after all, to escape from Andrew!

"The man lives there alone, I believe," he said. "I don't suppose there is any one to get us tea. He would only be embarrassed by our coming, and not know what to do."

Jeanne smiled reflectively.

"I do not think," she said, "that it would be easy to embarrass Mr. Andrew. However, if you like we will put it off to another afternoon, on one condition."

"Let me hear the condition at any rate," Cecil asked.

"That we go straight back, and that you show us that subterranean passage," Jeanne declared.

"Agreed!" Cecil answered. "I warn you that you will find it only damp and mouldy and depressing, but you shall certainly see it."

The girl moved toward the side of the boat, and stood leaning over, with her eyes fixed upon the island. Standing on the small grass plot in front of the cottage she could see the tall figure of a man with his face turned toward them. A faint smile parted her lips as she watched. She took out her handkerchief and waved it. The man for a moment stood motionless, and then raising his cap, held it for a moment above his head. The boat sped on, and very soon they were out of sight. She stood there, however, watching, until they had rounded the sandy spit and entered the creek which led into the harbour. There was something unusually piquant to her in the thought of that greeting with the man, whose response to it had been so unwilling, almost ungracious.

"Not another step!" the Princess declared. "I am going back at once."

"I too," Forrest declared. "Your smuggling ancestors, my dear De la Borne, must indeed have loved adventure, if they spent much of their time crawling about here like rats."

"As you will," Cecil answered. "The expedition is Miss Jeanne's, not mine."

"And I am going on," Jeanne declared. "I want to see where we come out on the beach."

"This way, then," Cecil said. "You need not be afraid to walk upright. The roof is six feet high all the way. You must tread carefully, though. There are plenty of holes and stones about."

The Princess and Forrest disappeared. Jeanne, with her skirts held high in one hand, and an electric torch in the other, followed Cecil slowly along the gloomy way. The walls were oozing with damp, glistening patches, like illuminated salt stains, and queer fungi started out from unexpected places. Sometimes their footsteps fell on the rock, awaking strange echoes down the gallery. Sometimes they sank deep into the sand. Cecil looked often behind, and once held out his hand to help his companion over a difficult place. At last he paused, and she heard him struggling to turn a key in a great worm-eaten door on their right.

"This is the room," he explained, "where they held their meetings, and where the stuff was hidden. It was used for more than twenty years, and the Customs' people never seemed to have had even an inkling of its existence."

He pushed the door open with difficulty. They found themselves in a gloomy chamber, with vaulted roof and stone floor. A faint streak of daylight from an opening somewhere in the roof, partially lit the place. Here, too, the walls were damp and the odour appalling. There were some fragments of broken barrels at one end, and an oak table in the middle of the floor. Jeanne looked round and shivered.

"Let us go on to the end," she said.

Cecil nodded, and they made their way on down the passage.

"The roof is getting lower now," he said. "You had better stoop a little."

She stopped short.

"What is that?" she asked fearfully.

A sound like rolling thunder, faint at first, but growing more distinct at every step, broke the chill silence of the place.

"The sea," Cecil answered. "We are getting near to the beach."

Jeanne nodded and crept on. Louder and louder the sound seemed to become, until at last she paused, half terrified.

"Where are we?" she gasped. "It sounds as though the sea were right over our heads."

Cecil shook his head.

"It is an illusion," he said. "The sound comes from the air-hole there. We are forty yards from the cliff still."

They crept on, until at last, after a turn in the gallery, they saw a faint glimmering of light. A few more yards and they came to a standstill.

"The entrance is boarded up, you see," Cecil said, "but you can see through the chinks. There is the sea just below, and the rope ladder used to hang from these staples."

She looked out. Sheer below was the sea, breaking upon the rocks and sending a torrent of spray into the air with every wave.

"We can't get out this way, then?" she asked.

He shook his head.

"No, we should want a rope ladder," he said, "and a boat. Have you seen enough?"

"More than enough," Jeanne answered. "Let us get back."

Jeanne sank into a garden seat a few minutes later with a little exclamation of relief.

"Never," she declared, "have I appreciated fresh air so much. I think, Mr. De la Borne, that smuggling, though it was a very romantic profession, must have had its unpleasant side."

Cecil nodded.

"There were more air-holes in those days," he said, "but our ancestors were a tougher race than we. Coarse brutes, most of them, I imagine," he added, lighting a cigarette. "Drank beer for breakfast, and smoked clay pipes before meals. Fancy if one had their constitutions and our tastes!"

"The two would scarcely go together," Jeanne remarked. "But after all I should think that absinthe and cigarettes are more destructive. I am dying for some tea. Let us go in and find the others."

Tea was set out in the hall, but only Engleton was there. Forrest and the Princess were walking slowly up and down the avenue.

"I imagine," the latter was saying drily, "that we are fairly free from eavesdroppers here. Now tell me what it is that you have to say, Nigel."

"I am bothered about Engleton," Forrest said. "I didn't like his insisting upon cutting last night. What do you think he meant by it?"

The Princess shrugged her shoulders.

"Nothing at all," she answered. "He may have thought that we were lucky together, and of course he knows that you are the best player. There is no reason why he should be willing to play with Cecil de la Borne, when by cutting with you he would be more likely to win."

"You think that that is all?" Forrest asked.

"I think so," the Princess answered. "What had you in your mind?"

"I wondered," Forrest said thoughtfully, "whether he had heard any of the gossip at the club."

The Princess frowned impatiently.

"For Heaven's sake, don't be imaginative, Nigel!" she declared. "If you give way like this you will lose your nerve in no time."

"Very well," Forrest said. "Let us take it for granted, then, that he did it only because he preferred to play with me to playing against me. What is to become of our little scheme if we cut as we did last night all the time?"

The Princess smiled.