RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

"Berenice," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1911

| Chapter I Chapter II Chapter III Chapter IV Chapter V Chapter VI Chapter VII Chapter VIII Chapter IX |

Chapter X Chapter XI Chapter XII Chapter XIII Chapter XIV Chapter XV Chapter XVI Chapter XVII |

"YOU may not care for the play," Ellison said eagerly. "You are of the old world, and Isteinism to you will simply spell chaos and vulgarity. But the woman! well, you will see her! I don't want to prejudice you by praises which you would certainly think extravagant! I will say nothing."

Matravers smiled gravely as he took his seat in the box and looked out with some wonder at the ill-lit, half-empty theatre.

"I am afraid," he said, "that I am very much out of place here, yet do not imagine that I bring with me any personal bias whatever. I know nothing of the play, and Isteinism is merely a phrase to me. To-night I have no individuality. I am a critic."

"So much depends," Ellison remarked, "upon the point of view. I am afraid that you are the last man in the world to have any sympathy with the decadent."

"I do not properly understand the use of the word 'decadent,'" Matravers said. "But you need not be alarmed as to my attitude. Whatever my own gods may be, I am no slave to them. Isteinism has its devotees, and whatever has had humanity and force enough in it to attract a following must at least demand a respectful attention from the Press. And to-night I am the Press!"

"I am sorry," Ellison remarked, glancing out into the gloomy well of the theatre with an impatient frown, "that there is so bad a house to-night. It is depressing to play seriously to a handful of people!"

"It will not affect my judgment," Matravers said.

"It will affect her acting, though," Ellison replied gloomily. "There are times when, even to us who know her strength, and are partial to her, she appears to act with difficulty,—to be encumbered with all the diffidence of the amateur. For a whole scene she will be little better than a stick. The change, when it comes, is like a sudden fire from Heaven. Something flashes into her face, she becomes inspired, she holds us breathless, hanging upon every word; it is then one realizes that she is a genius."

"Let us hope," Matravers said, "that some such moment may visit her to-night. One needs some compensation for a dinnerless evening, and such surroundings as these!"

He turned from the contemplation of the dreary, half-empty auditorium with a faint shudder. The theatre was an ancient and unpopular one. The hall-mark of failure and poverty was set alike upon the tawdry and faded hangings, the dust-eaten decorations and the rows of bare seats. It was a relief when the feeble overture came to an end, and the curtain was rung up. He settled himself down at once to a careful appreciation of the performance.

Matravers was not in any sense of the word a dramatic critic. He was a man of letters; amongst the elect he was reckoned a master in his art. He occupied a singular, in many respects a unique, position. But in matters dramatic, he confessed to an ignorance which was strictly actual and in no way assumed. His presence at the New Theatre on that night, which was to become for him a very memorable one, was purely a matter of chance and good nature. The greatest of London dailies had decided to grant a passing notice to the extraordinary series of plays, which in flightier journals had provoked something between the blankest wonderment and the most boisterous ridicule. Their critic was ill—Matravers, who had at first laughed at the idea, had consented after much pressure to take his place. He felt himself from the first confronted with a difficult task, yet he entered upon it with a certain grave seriousness, characteristic of the man, anxious to arrive at and to comprehend the true meaning of what in its first crude presentation to his senses seemed wholly devoid of anything pertaining to art.

The first act was almost over before the heroine of the play, and the actress concerning whose merits there was already some difference of opinion, appeared. A little burst of applause, half-hearted from the house generally, enthusiastic from a few, greeted her entrance. Ellison, watching his companion's face closely, was gratified to find a distinct change there. In Matravers' altered expression was something more than the transitory sensation of pleasure, called up by the unexpected appearance of a very beautiful woman. The whole impassiveness of that calm, almost marble-still face, with its set, cold lips, and slightly wearied eyes, had suddenly disappeared, and what Ellison had hoped for had arrived. Matravers was, without doubt, interested.

Yet the woman, whose appearance had caused a certain thrill to quiver through the house, and whose coming had certainly been an event to Matravers, did absolutely nothing for the remainder of that dreary first act to redeem the forlorn play, or to justify her own peculiar reputation. She acted languidly, her enunciation was imperfect, her gestures were forced and inapt. When the curtain went down upon the first act, Matravers was looking grave. Ellison was obviously uneasy.

"Berenice," he muttered, "is not herself to-night. She will improve. You must suspend your judgment."

Matravers fingered his programme nervously.

"You are interested in this production, Ellison," he said, "and I should be sorry to write anything likely to do it harm. I think it would be better if I went away now. I cannot be blamed if I decline to give an opinion on anything which I have only partially seen."

Ellison shook his head.

"No, I'll chance it," he said. "Don't go. You haven't seen Berenice at her best yet. You have not seen her at all, in fact."

"What I have seen," Matravers said gravely, "I do not like."

"At least," Ellison protested, "she is beautiful."

"According to what canons of beauty, I wonder?" Matravers remarked. "I hold myself a very poor judge of woman's looks, but I can at least recognize the classical and Renaissance standards. The beauty which this woman possesses, if any, is of the decadent order. I do not recognize it. I cannot appreciate it!"

Ellison laughed softly. He had a marvellous belief in this woman and in her power of attracting.

"You are not a woman's man, Matravers, or you would know that her beauty is not a matter of curves and colouring! You cannot judge her as a piece of statuary. All your remarks you would retract if you talked with her for five minutes. I am not sure," he continued, "that I dare not warrant you to retract them before this evening is over. At least, I ask you to stay. I will run my risk of your pulverization."

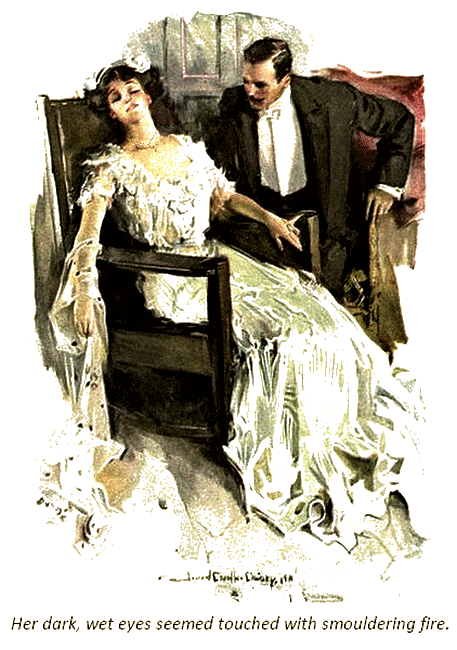

The curtain rang up again, the play proceeded. But not the same play—at least, so it seemed to Matravers—not the same play, surely not the same woman! A situation improbable enough, but dramatic, had occurred at the very beginning of the second act. She had risen to the opportunity, triumphed over it, electrified her audience, delighted Ellison, moved Matravers to silent wonder. Her personality seemed to have dilated with the flash of genius which Matravers himself had been amongst the first to recognize. The strange pallor of her face seemed no longer the legacy of ill-health; her eyes, wonderfully soft and dark, were lit now with all manner of strange fires. She carried herself with supreme grace; there was not the faintest suspicion of staginess in any one of her movements. And more wonderful than anything to Matravers, himself a delighted worshipper of the beautiful in all human sounds, was that marvellously sweet voice, so low and yet so clear, expressing with perfect art the highest and most hallowed emotions, with the least amount of actual sound. She seemed to pour out the vial of her wrath, her outraged womanhood in tones raised little above a whisper, and the man who fronted her seemed turned into the actual semblance of an ashamed and unclean thing. Matravers made no secret now of his interest. He had drawn his chair to the front of the box, and the footlights fell full upon his pale, studious face turned with grave and absolute attention upon the little drama working itself out upon the stage. Ellison in the midst of his jubilation found time to notice what to him seemed a somewhat singular incident. In crossing the stage her eyes had for a moment met Matravers' earnest gaze, and Ellison could almost have declared that a faint, welcoming light flashed for a moment from the woman to the man. Yet he was sure that the two were strangers. They had never met—her very name had been unknown to him. It must have been his fancy.

The curtain fell upon the second and final act amidst as much applause as the sparsely filled theatre could offer; but mingled with it, almost as the last words of her final speech had left her lips, came a curious hoarse cry from somewhere in the cheaper seats near the back of the house. It was heard very distinctly in every part; it rang out upon the deep quivering stillness which reigns for a second between the end of a play which has left the audience spellbound, and the burst of applause which is its first reawakening instinct. It was drowned in less than a moment, yet many people turned their startled heads towards the rows of back seats. Matravers, one of the first to hear it, was one of the most interested—perhaps because his sensitive ears had recognized in it that peculiar inflection, the true ring of earnestness. For it was essentially a human cry, a cry of sorrow, a strange note charged in its very hoarseness and spontaneity with an unutterable pathos. It was as though it had been actually drawn from the heart to the lips, and long after the house had become deserted, Matravers stood there, his hands resting upon the edge of the box, and his dark face turned steadfastly to that far-away corner, where it seemed to him that he could see a solitary, human figure, sitting with bowed head amongst the wilderness of empty seats.

Ellison touched him upon the elbow.

"You must come with me and be presented to Berenice," he said.

Matravers shook his head.

"Please excuse me," he said; "I would really rather not."

Ellison held out a crumpled half-sheet of notepaper.

"This has just been brought in to me," he said.

Matravers read the single line, hastily written, and in pencil:—

"Bring your friend to me.—B."

"It will scarcely take us a moment," Ellison continued. "Don't stop to put on your coat; we are the last in the theatre now."

Matravers, whose will was usually a very dominant one, found himself calmly obeying his companion. Following Ellison, he was bustled down a long, narrow passage, across a bare wilderness of boards and odd pieces of scenery, to the door of a room immediately behind the stage. As Ellison raised his fingers to knock, it was opened from the inside, and Berenice came out wrapped from head to foot in a black satin coat, and with a piece of white lace twisted around her hair. She stopped when she saw the two men, and held out her hand to Ellison, who immediately introduced Matravers.

Again Ellison fancied that in her greeting of him there were some traces of a former knowledge. But nothing in her words or in his alluded to it.

"I am very much honoured," Matravers said simply. "I am a rare attendant at the theatre, and your performance gave me great pleasure."

"I am very glad," she answered. "Do you know that you made me wretchedly nervous? I was told just as I was going on that you had come to smash us all to atoms in that terrible Day."

"I came as a critic," he answered, "but I am a very incompetent one. Perhaps you will appreciate my ignorance more when I tell you that this is my first visit behind the scenes of a theatre."

She laughed softly, and they looked around together at the dimly burning gas-lights, the creaking scenery being drawn back from the stage, the woman with a brush and mop sweeping, and at that dismal perspective of holland-shrouded auditorium beyond, now quite deserted.

"At least," she said, "your impressions cannot be mixed ones. It is hideous here."

He did not contradict her; and they both ignored Ellison's murmured compliment.

"It is very draughty," he remarked, "and you seem cold; we must not keep you here. May we—can I," he added, glancing down the stone passage, "show you to your carriage?"

She laughed softly.

"You may come with me," she said, "but our exit is like a rabbit burrow; we must go in single file, and almost on hands and knees."

She led the way, and they followed her into the street. A small brougham was waiting at the door, and her maid was standing by it. The commissionaire stood away, and Matravers closed the carriage door upon them. Her white, ungloved hand, loaded—overloaded it seemed to him—with rings, stole through the window, and he held it for a moment in his. He felt somehow that he was expected to say something. She was looking at him very intently. There was some powder on her cheeks, which he noted with an instinctive thrill of aversion.

"Shall I tell him home?" he asked.

"If you please," she answered.

"Madam!" her maid interposed.

"Home, please," Berenice said calmly. "Good-by, Mr. Matravers."

"Good night."

The carriage rolled away. At the corner of the street Berenice pulled the check-string. "The Milan Restaurant," she told the man briefly.

Matravers and Ellison lit their cigarettes and strolled away on foot. At the corner of the street Ellison had an inspiration.

"Let us," he said, "have some supper somewhere."

Matravers shook his head.

"I really have a great deal of work to do," he said, "and I must write this notice for the Day. I think that I will go straight home."

Ellison thrust his arm through his companion's, and called a hansom.

"It will only take us half an hour," he declared, "and we will go to one of the fashionable places. You will be amused! Come! It all enters, you know, into your revised scheme of life—the attainment of a fuller and more catholic knowledge of your fellow-creatures. We will see our fellow-creatures en fete."

Matravers suffered himself to be persuaded. They drove to a restaurant close at hand, and stood for a moment at the entrance looking for seats. The room was crowded.

"I will go," Ellison said, "and find the director. He knows me well, and he will find me a table."

He elbowed his way up to the further end of the apartment. Matravers remained a somewhat conspicuous figure in the doorway looking from one to another of the little parties with a smile, half amused, half interested. Suddenly his face became grave,—his heart gave an unaccustomed leap! He stood quite still, his eyes fixed upon the bent head and white shoulders of a woman only a few yards away from him. Almost at the same moment Berenice looked up and their eyes met. The colour left her cheeks,—she was ghastly pale! A sentence which she had just begun died away upon her lips; her companion, who was intent upon the wine list, noticed nothing. She made a movement as though to rise. Simultaneously Matravers turned upon his heel and left the room.

Ellison came hurrying back in a few moments and looked in vain for his companion. As he stood there watching the throng of people, Berenice called him to her.

"Your friend," she said, "has gone away. He stood for a moment in the doorway like Banquo's ghost, and then he disappeared."

Ellison looked vaguely bewildered.

"Matravers is an odd sort," he remarked. "I suppose it is one of the penalties of genius to be compelled to do eccentric things. I must have my supper alone."

"Or with us," she said. "You know Mr. Thorndyke, don't you? There is plenty of room here."

MATRAVERS stood at an open window, reading a note by the grey dawn light. Below him stretched the broad thoroughfare of Piccadilly, noiseless, shadowy, deserted. He had thrown up the window overcome by a sudden sense of suffocation, and a chill, damp breeze came stealing in, cooling his parched forehead and hot, dry eyes. For the last two or three hours he had been working with an unwonted and rare zest; it had happened quite by chance, for as a rule he was a man of regular, even mechanical habits. But to-night he scarcely knew himself,—he had all the sensations of a man who had passed through a new and altogether unexpected experience. At midnight he had let himself into his room after that swift, impulsive departure from the Milan, and had dropped by chance into the chair before his writing-table. The sight of his last unfinished sentence, abruptly abandoned in the centre of a neatly written page of manuscript, had fascinated him, and as he sat there idly with the loose sheet in his hands, holding it so that the lamplight might fall upon its very legible characters, an idea flashed into his brain,—an idea which had persistently eluded him for days. With the sudden stimulus of a purely mental activity, he had hastily thrown aside his outdoor garment, and had written for several hours with a readiness and facility which seemed, somehow, for the last few days to have been denied to him.

He had become his old self again,—the events of the evening lay already far behind. Then had come a soft knocking at the door, followed by the apologetic entrance of his servant bearing a note upon which his name was written in hasty characters with an "Immediate" scrawled, as though by an after-thought, upon the left-hand corner. He had torn it open wondering at the woman's writing, and glanced at its brief contents carelessly enough,—but since then he had done no work. For the present he was not likely to do any more.

The cold breeze, acting like a tonic upon his dazed senses, awoke in him also a peculiar restlessness, a feeling of intolerable restraint at the close environment of his little room and its associations. Its atmosphere had suddenly become stifling. He caught up his cloak and hat, and walked out again into the silent street; it seemed to him, momentarily forgetful of the hour, like a city of the dead into which he had wandered.

As he turned, from habit, towards the Park, the great houses on his right frowned down upon him lightless and lifeless. The broad pavement, pressed a few hours ago, and so soon to be pressed again by the steps of an innumerable multitude, was deserted; his own footfall seemed to awaken a strange and curiously persistent echo, as though some one were indeed following him on the opposite side of the way under the shadow of the drooping lime trees. Once he stopped and listened. The footsteps ceased too. There was no one! With a faint smile at the illusion to which he had for a moment yielded, he continued his walk.

Before him the outline of the arch stood out with gloomy distinctness against a cold, lowering background of vapourous sky. Like a man who was still half dreaming, he crossed the road and entered the Park, making his way towards the trees. There was a spot about half-way down, where, in the afternoons, he usually sat. Near it he found two chairs, one on top of the other; he removed the upper one and sat down, crossing his legs and lighting a cigarette which he took from his case. Then in a transitory return of his ordinary state of mind he laughed softly to himself. People would say that he was going mad.

Through half-closed eyes he looked out upon the broad drive. With the aid of an imagination naturally powerful, he was passing with marvellous facility into an unreal world of his own creation. The scene remained the same, but the environment changed as though by magic. Sunshine pierced the grey veil of clouds, gay voices and laughter broke the chill silence. The horn of a four-in-hand sounded from the corner, the path before him was thronged with men and women whose rustling skirts brushed often against his knees as they made their way with difficulty along the promenade. A glittering show of carriages and coaches swept past the railings; the air was full of the sound of the trampling of horses and the rolling of wheels. With a mental restraint of which he was all the time half-conscious, he kept back the final effort of his imagination for some time; but it came at last.

A victoria, drawn by a single dark bay horse, with servants in quiet liveries, drew up at the paling, and a woman leaning back amongst the cushions looked out at him across the sea of faces as she had indeed looked more than once. She was surrounded by handsomer women in more elaborate toilettes and more splendid equipages. Her cheeks were pale, and she was undoubtedly thin. Nevertheless, to other people as well as to him, she was a personality. Even then he seemed to feel the little stir which always passed like electricity into the air directly her carriage was stayed. When she had come, when he was perfectly sure of her, and indeed under the spell of her near presence, he drew that note again from his pocket and read it.

18, LARGE STREET, W.

12.30.

I told you a lie! and I feel that you will never forgive me! Yet I want to explain it. There is something I want you to know! Will you come and see me? I shall be at home until one o'clock to-morrow morning, or, if the afternoon suits you better, from 4 to 6.

BERENICE.

A lie! Yes, it was that. To him, an inveterate lover of truth, the offence had seemed wholly unpardonable. He had set himself to forget the woman and the incident as something altogether beneath his recollection. The night, with its host of strange, half-awakened sensations, was a memory to be lived down, to be crushed altogether. For him, doubtless, that lie had been a providence. It put a stop to any further intercourse between them,—it stamped her at once with the hall-mark of unworthiness. Yet he knew that he was disappointed; disappointment was, perhaps, a mild word. He had walked through the streets with Ellison, after that meeting with her at the theatre, conscious of an unwonted buoyancy of spirits, feeling that he had drawn into his life a new experience which promised to be a very pleasant one.

There were things about the woman which had not pleased him, but they were, on the whole, merely superficial incidents, accidents he chose to think, of her environment. He had even permitted himself to look forward to their next meeting, to a definite continuance of their acquaintance. Standing in the doorway of the brilliantly lighted Milan, he had looked in at the vivid little scene with a certain eager tolerance,—there was much, after all, that was attractive in this side of life, so much that was worth cultivating; he blamed himself that he had stood aloof from it for so long.

Then their eyes had met, he had seen her sudden start, had felt his heart sink like lead. She was a creature of common clay after all! His eyes rested for a moment upon her companion, a man well known to him, though of a class for whom his contempt was great, and with whom he had no kinship. She was like this then! It was a pity.

His cigarette went out, and a rain-drop, which had been hovering upon a leaf above him, fell with a splash upon the sheet of heavy white paper. He rose to his feet, stiff and chilled and disillusioned. His little ghost-world of fancies had faded away. Morning had come, and eastwards, a single shaft of cold sunlight had pierced the grey sky.

AT ten o'clock he breakfasted, after three hours' sleep and a cold bath. In the bright, yet soft spring daylight, the lines of his face had relaxed, and the pallor of his cheeks was less unnatural. He was still a man of remarkable appearance; his features were strong and firmly chiselled, his forehead was square and almost hard. He wore no beard, but a slight, black moustache only half-concealed a delicate and sensitive mouth. His complexion and his soft grey eyes were alike possessed of a singular clearness, as though they were, indeed, the indices of a temperate and well-contained life. His dress, and every movement and detail of his person, were characterized by an extreme deliberation; his whole appearance bespoke a peculiar and almost feminine fastidiousness. The few appointments of his simple meal were the most perfect of their kind. A delicate vase of freshly cut flowers stood on the centre of the spotless table-cloth,—the hangings and colouring of the apartment were softly harmonious. The walls were hung with fine engravings, with here and there a brilliant little water-colour of the school of Corot; a few marble and bronze statuettes were scattered about on the mantelpiece and on brackets. There was nothing particularly striking anywhere, yet there was nothing on which the eye could not rest with pleasure.

At half-past ten he lit a cigarette, and sat down at his desk. He wrote quite steadily for an hour; at the end of that time he pinned together the result of his work, and wrote a hasty note.

113, PICCADILLY.

DEAR MR. HASLUP,—

I went last night to the New Theatre, and I send you my views as to what I saw there. But I beg that you will remember my absolute ignorance on all matters pertaining to the modern drama, and use your own discretion entirely as to the disposal of the enclosed. I do not feel myself, in any sense of the word, a competent critic, and I trust that you will not feel yourself under the least obligation to give to my views the weight of your journal.

I remain,

Yours truly,

JOHN MATRAVERS.

His finger was upon the bell, when his servant entered, bearing a note upon a salver. Matravers glanced at the handwriting already becoming familiar to him, recognizing, too, the faint odour of violets which seemed to escape into the room as his fingers broke the seal.

It is half-past eleven and you have not come! Does that mean that you will not listen to me, that you mean to judge me unheard? You will not be so unkind! I shall remain indoors until one o'clock, and I shall expect you.

BERENICE.

Matravers laid the note down, and covered it with a paper-weight. Then he sealed his own letter, and gave it, with the manuscript, to his servant. The man withdrew, and Matravers continued his writing.

He worked steadily until two o'clock. Then a simple luncheon was brought in to him, and upon the tray another note. Matravers took it with some hesitation, and read it thoughtfully.

TWO O'CLOCK.

You have made up your mind, then, not to come. Very well, I too am determined. If you will not come to me, I shall come to you! I shall remain in until four o'clock. You may expect to see me any time after then.

BERENICE.

Matravers ate his luncheon and pondered, finally deciding to abandon a struggle in which his was obviously the weaker position. He lingered for a while over his coffee; at three o'clock he retired for a few moments into his dressing-room, and then descending the stairs, made his way out into the street.

He had told himself only a few hours back that he would be wise to ignore this summons from a woman, the ways of whose life must lie very far indeed from his. Yet he knew that his meeting with her had affected him as nothing of the sort had ever affected him before—a man unimpressionable where women were concerned, and ever devoted to and cultivating a somewhat unnatural exclusiveness. Her first note he had been content to ignore,—she might have written it in a fit of pique—but the second had made him thoughtful. Her very persistence was characteristic. Perhaps after all she was in the right—he had arrived too hastily at an ignoble conclusion. Her attitude towards him was curiously unconventional; it was an attitude such as none of the few women with whom he had ever been brought into contact would have dreamed of assuming. But none the less it had for him a fascination which he could not measure or define,—it had awakened a new sensation, which, as a philosopher, he was anxious to probe. The mysticism of his early morning wanderings seemed to him, as he walked leisurely through the sunlit streets, in a sense ridiculous. After all it was a little thing that he was going to do; he was going to make, against his will, an afternoon call. To other men it would have seemed less than nothing. Albeit he knew he was about to draw into his life a new experience.

He rang the bell at Number 18, Large Street, and gave his card to the trim little maidservant who opened the door. In a minute or two she returned, and invited him to follow her upstairs; her mistress was in, and would see him at once. She led the way up the broad staircase into a room which could, perhaps, be most aptly described as a feminine den. The walls, above the low bookshelves which bordered the whole apartment, were hung with a medley of water-colours and photographs, water-colours which a single glance showed him were good, and of the school then most in vogue. The carpet was soft and thick, divans and easy chairs filled with cushions were plentiful. By the side of one of these, which bore signs of recent occupation, was a reading stand, and upon it a Shakespeare, and a volume of his own critical essays.

To him, with all his senses quickened by an intense curiosity, there seemed to hang about the atmosphere of the room that subtle odour of femininity which, in the case of a man, would probably have been represented by tobacco smoke. A Sevres jar of Neapolitan violets stood upon the table near the divan. Henceforth the perfume of violets seemed a thing apart from the perfume of all other flowers to the man who stood there waiting, himself with a few of the light purple blossoms in the buttonhole of his frock coat.

SHE came to him so noiselessly, that for a moment or two he was unaware of her entrance. There was neither the rustle of skirts nor the sound of any movement to apprise him of it, yet he became suddenly conscious that he was not alone. He turned around at once and saw her standing within a few feet of him. She held out her hand frankly.

"So you have come," she said; "I thought that you would. But then you had very little choice, had you?" she added with a little laugh.

She passed him, and deliberately seated herself amongst a pile of cushions on the divan nearest her reading stand. For the moment he neglected her gestured invitation, and remained standing, looking at her.

"I was very glad to come," he said simply.

She shook her head.

"You were afraid of my threat. You were afraid that I might come to you. Well, it is probable, almost certain that I should have come. You have saved yourself from that, at any rate."

Although the situation was a novel one to him, he was not in the least embarrassed. He was altogether too sincere to be possessed of any self-consciousness. He found himself at last actually in the presence of the woman who, since first he had seen her, months ago, driving in the Park, had been constantly in his thoughts, and he began to wonder with perfect clearness of judgment wherein lay her peculiar fascination! That she was handsome, of her type, went for nothing. The world was full of more beautiful women whom he saw day by day without the faintest thrill of interest. Besides, her face was too pale and her form too thin for exceptional beauty. There must be something else,—something about her personality which refused to lend itself to any absolute analysis. She was perfectly dressed,—he realized that, because he was never afterwards able to recall exactly what she wore. Her eyes were soft and dark and luminous,—soft with a light the power of which he was not slow to recognize.

But none of these things were of any important account in reckoning with the woman. He became convinced, in those few moments of deliberate observation, that there was nothing in her "personnel" which could justify her reputation. On the whole he was glad of it. Any other form of attraction was more welcome to him than a purely physical one!

"First of all," she began, leaning forward and looking at him over her interlaced fingers; "I want you to tell me this! You will answer me faithfully, I know. What did you think of my writing to you, of my persistence? Tell me exactly what you thought."

"I was surprised," he answered; "how could I help it? I was surprised, too," he added, "to find that I wanted very much to come."

"The women whom you know," she said quietly,—"I suppose you do know some,—would not have done such a thing. Some people say that I am mad! One may as well try to live up to one's reputation; I have taken a little of the license of madness."

"It was unusual, perhaps," he admitted; "but who is not weary of usual things? I gathered from your note that you had something to explain. I was anxious to hear what that explanation could be."

She was silent for a moment, her eyes fixed upon vacancy, a faint smile at the corners of her lips.

"First," she said, "let me tell you this. I want to have you understand why I was anxious that you should not think worse of me than I deserved. I am rather a spoilt woman. I have grown used to having my own way; I wanted to know you, I have wanted to for some time. We have passed one another day after day; I knew quite well all the time who you were, and it seemed so stupid! Do you know once or twice I have had an insane desire to come right up to your chair and break in upon your meditations,—hold out my hand and make you talk to me? That would have been worse than this, would it not? But I firmly believe that I should have done it some day. So you see I wrote my little note in self-defence."

"I do not know that I should have been so completely surprised after all," he said. "I, too, have felt something of what you have expressed. I have been interested in your comings and your goings. But then you knew that, or you would never have written to me."

"One sacrifices so much," she murmured, "on the altars of the modern Goddess. We live in such a tiny compass,—nothing ever happens. It is only psychologically that one's emotions can be reached at all. Events are quite out of date. I am speaking from a woman's point of view."

"You should have lived," he said, smiling, "in the days of Joan of Arc."

"No doubt," she answered, "I should have found that equally dull. What I was endeavouring to do was, first of all to plead some justification for wanting to know you. For a woman there is nothing left but the study of personalities."

"Mine," he answered with a faint gleam in his eyes, "is very much at your service."

"I am going to take you at your word," she warned him.

"You will be very much disappointed. I am perfectly willing to be dissected, but the result will be inadequate."

She leaned back amongst the cushions and looked at him thoughtfully.

"Listen," she said; "I can tell you something of your history, as you will see. I want you to fill in the blanks."

"Mine," he murmured, "will be the greater task. My life is a record of blank places. The history is to come."

"This," she said, "is the extent of my knowledge. You were the second son of Sir Lionel Matravers, and you have been an orphan since you were very young. You were meant to take Holy Orders, but when the time came you declined. At Oxford you did very well indeed. You established a brilliant reputation as a classical scholar, and you became a fellow of St. John's.

"It was whilst you were there that you wrote Studies in Character. Two years ago, I do not know why, you gave up your fellowship and came to London. You took up the editorship of a Review—the Bi-Weekly, I think—but you resigned it on a matter of principle. You have a somewhat curious reputation. The Scrutineer invariably alludes to you as the Apostle of AEstheticism. You are reported to have fixed views as to the conduct of life, down even to its most trifling details. That sounds unpleasant, but it probably isn't altogether true.... Don't interrupt, please! You have no intimate friends, but you go sometimes into society. You are apparently a mixture of poet, philosopher, and man of fashion. I have heard you spoken of more than once as a disciple of Epicurus. You also, in the course of your literary work, review novels—unfortunately for me—and six months ago you were the cause of my nearly crying my eyes out. It was perhaps silly of me to attempt, without any literary experience, to write a modern story, but my own life supplied the motive, and at least I was faithful to what I felt and knew. No one else has ever said such cruel things about my work.

"Woman-like, you see, I repay my injuries by becoming interested in you. If you had praised my book, I daresay I should never have thought of you at all. Then there is one thing more. Every day you sit in the Park close to where I stop, and—you look at me. It seems as though we had often spoken there. Shall I tell you what I have been vain enough to think sometimes?

"I have watched you from a distance, often before you have seen me. You always sit in the same attitude, your eyebrows are a little contracted, there is generally the ghost of a smile upon your lips. You are like an outsider who has come to look upon a brilliant show. I could fancy that you have clothed yourself in the personality of that young Roman noble whose name you have made so famous, and from another age were gazing tolerantly and even kindly upon the folly and the pageantry which have survived for two thousand years. And then I have taken my little place in the procession, and I have fancied that a subtle change has stolen into your face. You have looked at me as gravely as ever, but no longer as an impersonal spectator.

"It is as though I have seemed a live person to you, and the others, mummies. Once the change came so swiftly that I smiled at you,—I could not help it,—and you looked away."

"I remember it distinctly," he interrupted. "I thought the smile was for some one behind me."

She shook her head.

"It was for you. Now I have finished. Fill in the blanks, please."

He was content to answer her in the same strain. The effect of her complete naturalness was already upon him.

"So far as my personal history is concerned," he told her, "you are wonderfully correct. There is nothing more to be said about it. I gave up my fellowship at Oxford because I have always been convinced of the increasing narrowness and limitations of purely academic culture and scholarship. I was afraid of what I should become as an old man, of what I was already growing into. I wanted to have a closer grip upon human things, to be in more sympathetic relations with the great world of my fellow-men. Can you understand me, I wonder? The influences of a university town are too purely scholarly to produce literary work of wide human interest. London had always fascinated me—though as yet I have met with many disappointments. As to the Bi-Weekly, it was my first idea to undertake no fixed literary work, and it was only after great pressure that I took it for a time. As you know, my editorship was a failure."

He paused for a moment or two, and looked steadily at her. He was anxious to watch the effect of what he was going to say.

"You have mentioned my review upon your novel in the Bi-Weekly. I cannot say that I am sorry I wrote it. I never attacked a book with so much pleasure. But I am very sorry indeed that you should have written it. With your gifts you could have given to the world something better than a mere psychological debauch!"

She laughed softly, but genuinely.

"I adore sincerity," she exclaimed, "and it is so many years since I was actually scolded. A 'psychological debauch' is delightful. But I cannot help my views, can I? My experiences were made for me! I became the creature of circumstances. No one is morally responsible for their opinions."

"There are things," he said, "which find their way into our thoughts and consciousness, but of which it would be considered flagrantly bad taste to speak. And there are things in the world which exist, which have existed from time immemorial, the evil legacy of countless generations, of which it seems to me to be equally bad taste to write. Art has a limitless choice of subjects. I would not have you sully your fine gifts by writing of anything save of the beautiful."

"This is rank hedonism," she laughed. "It is a survival of your academic days."

"Some day," he answered, "we will talk more fully of this. It is a little early for us to discuss a subject upon which we hold such opposite views."

"You are afraid that we might quarrel!"

He shook his head.

"No, not that! Only as I am something of an idealist, and you, I suppose, have placed yourself amongst the ranks of the realists, we should scarcely meet upon a common basis. But will you forgive me if I say so—I am very sure that some day you will be a deserter?"

"And why?"

"I do not know anything of your history," he continued gently, "nor am I asking for your confidence. Only in your story there was a personal note, which seemed to me to somehow explain the bitterness and directness with which you wrote—of certain subjects. I think that you yourself have had trouble—or perhaps a dear friend has suffered, and her grief has become yours. There was a little poison in your pen, I think. Never mind! We shall be friends, and I shall watch it pass away!"

"Friends," she repeated with a certain wistfulness in her tone. "But have you forgotten—what you came for?"

"I do not think," he said slowly, "that it is of much consequence."

"But it is," she insisted. "You asked me distinctly where I wished to be driven to from the theatre, and I told you—home! All the time I knew that I was going to have supper with Mr. Thorndyke at the Milan! Morally I lied to you!"

"Why?" he asked.

"I cannot tell you," she answered; "it was an impulse. I thought nothing of accepting the man's invitation. You know him, I daresay. He is a millionaire, and it is his money which supports the theatre. He has asked me several times, and although personally I dislike him, he has, of course, a certain claim upon my acquaintance. I have made excuses once or twice. Last night was the first time I have ever been out anywhere with him. I do not of course pretend to be in the least conventional—I have always permitted myself the utmost liberty of action. Yet—I had wanted so much to know you—I was afraid of prejudicing you.... After all, you see, I have no explanation. It was just an impulse. I have hated myself for it; but it is done!"

"It was," he said, "a trifle of no importance. We will forget it."

A gleam of gratitude shone in her dark eyes. Her head drooped a little. He fancied that her voice was not quite so steady.

"It is good," she said, "to hear you say that."

He looked around the room, and back into her face. Some dim foreknowledge of what was to come between them seemed to flash before his eyes. It was like a sudden glimpse into that unseen world so close at hand, in which he—that Roman noble—had at any rate implicitly believed. There was a faint smile upon his face as his eyes met hers.

"At least," he said, "I shall be able to come and talk with you now at the railing, instead of watching you from my chair. For you were quite right in what you said just now. I have watched for you every day—for many days."

"You will be able to come," she said gravely, "if you care to. You mix so little with the men who love to talk scandal of a woman, that you may never have heard them—talk of me. But they do, I know! I hear all about it—it used to amuse me! You have the reputation of ultra exclusiveness! If you and I are known to be friends, you may have to risk losing it."

His brows were slightly contracted, and he had half closed his eyes—a habit of his when anything was said which offended his taste.

"I wonder whether you would mind not talking like that," he said.

"Why not? I would not have you hear these things from other people. It is best to be truthful, is it not? To run no risk of any misunderstandings."

"There is no fear of anything of that sort," he said calmly. "I do not pretend to be a magician or a diviner, yet I think I know you for what you are, and it is sufficient. Some day——"

He broke off in the middle of a sentence. The door had opened. A man stood upon the threshold. The servant announced him—Mr. Thorndyke.

Matravers rose at once to his feet. He had a habit—the outcome, doubtless, of his epicurean tenets, of leaving at once, and at any costs, society not wholly agreeable to him. He bowed coldly to the man who was already greeting Berenice, and who was carrying a great bunch of Parma violets.

Mr. Thorndyke was evidently astonished at his presence—and not agreeably.

"Have you come, Mr. Matravers," he asked coldly, "to make your peace?"

"I am not aware," Matravers answered calmly, "of any reason why I should do so."

Mr. Thorndyke raised his eyebrows, and drew an afternoon paper from his pocket.

"This is your writing, is it not?" he asked.

Matravers glanced at the paragraph.

"Certainly!"

Mr. Thorndyke threw the paper upon the table.

"Well," he said, "I have no doubt it is an excellent piece of literary work—a satire I suppose you would call it—and I must congratulate you upon its complete success. I don't mind running the theatre at a financial loss, but I have a distinct objection to being made a laughing stock of. I suppose this paper appeared about two hours ago, and already I can't move a yard without having to suffer the condolences of some sympathizing ass. I shall close the theatre next week."

"That is naturally," Matravers said, "a matter of complete indifference to me. In the cause of art I should say that you will do well, unless you can select a play from a very different source. What I wrote of the performance last night, I wrote according to my convictions. You," he added, turning to Berenice, "will at least believe that, I am sure!"

"Most certainly I do," she assured him, holding out her hand. "Must you really go? You will come and see me again—very soon?"

He bowed over her fingers, and then their eyes met for a moment. She was very pale, but she looked at him bravely. He realized suddenly that Mr. Thorndyke's threat was a serious blow to her.

"I am very sorry," he said. "You will not bear me any ill will?"

"None!" she answered; "you may be sure of that!"

She walked with him to the open door, outside which the servant was waiting to show him downstairs.

"You will come and see me again—very soon?" she repeated.

"Yes," he answered simply, "if I may I shall come again! I will come as soon as you care to have me!"

MATRAVERS passed out into the street with a curious admixture of sensations in a mind usually so free from any confusion of sentiments or ideas. The few words which he had been compelled to exchange with Thorndyke had grated very much against his sense of what was seemly; he was on the whole both repelled and fascinated by the incidents of this visit of his. Yet as he walked leisurely homewards through the bright, crowded streets, he recognized the existence of that strange personal charm in Berenice of which so many people had written and spoken. He himself had become subject to it in some slight degree, not enough, indeed, to engross his mind, yet enough to prevent any feeling of disappointment at the result of his visit.

She was not an ordinary woman—she was not an ordinarily clever woman. She did not belong to any type with which he was acquainted. She must for ever occupy a place of her own in his thoughts and in his estimation. It was a place very well defined, he told himself, and by no means within that inner circle of his brain and heart wherein lay the few things in life sweet and precious to him. The vague excitement of the early morning seemed to him now, as he moved calmly along the crowded, fashionable thoroughfare, a thing altogether unreal and unnatural. He had been in an emotional frame of mind, he told himself with a quiet smile, when the sight of those few lines in a handwriting then unknown had so curiously stirred him. Now that he had seen and spoken to her, her personality would recede to its proper proportions, the old philosophic calm which hung around him in his studious life like a mantle would have no further disturbance.

And then he suffered a rude shock! As he passed the corner of a street, the perfume of Neapolitan violets came floating out from a florist's shop upon the warm sunlit air. Every fibre of his being quivered with a sudden emotion! The interior of that little room was before him, and a woman's eyes looked into his. He clenched his hands and walked swiftly on, with pale face and rigid lips, like a man oppressed by some acute physical pain.

There must be nothing of this for him! It was part of a world which was not his world—of which he must never even be a temporary denizen. The thing passed away! With studious care he fixed his mind upon trifles. There was a crease in his silk hat, clearly visible as he glanced at his reflection in a plate-glass window. He turned into Scott's, and waited whilst it was ironed. Then he walked homewards and spent the remainder of the day carefully revising a bundle of proofs which he found on his table fresh from the printer.

On the following morning he lunched at his club. Somehow, although he was in no sense of the word an unpopular man, it was a rare thing for any one to seek his company uninvited. The scholarly exclusiveness of his Oxford days had not been altogether brushed off in this contact with a larger and more spontaneous social life, and he figured in a world which would gladly have known more of him, as a man of courteous but severe reserve.

To-day he occupied his usual round table set in an alcove before a tall window. For a recluse, he always found a singular pleasure in watching the faces of the people in that broad living stream, little units in the wheeling cycle of humanity of which he too felt himself to be a part; but to-day his eyes were idle, and his sympathies obstructed. Although a pronounced epicure in both food and drink, he passed a new and delicate entree, and not only ordered the wrong claret, but drank it without a grimace. The world of his sensations had been rudely disturbed. For the moment his sense of proportions was at fault, and before luncheon was over it received a further shock. A handsomely appointed drag rattled past the club on its way into Piccadilly. The woman who occupied the front seat turned to look at the window as they passed, with some evident curiosity—and their eyes met. Matravers set down the glass, which he had been in the act of raising to his lips, untasted.

"Berenice and her Father Confessor!" he heard some one remark lightly from the next table. "Pity some one can't teach Thorndyke how to drive! He's a disgrace to the Four-in-hand!"

It was Berenice! The sight of her in such intimate association with a man utterly distasteful to him was one before which he winced and suffered. He was aware of a new and altogether undesired experience. To rid himself of it with all possible speed, he finished his lunch abruptly, and lighting a cigarette, started back to his rooms.

On the way he came face to face with Ellison, and the two men stood together upon the pavement for a moment or two.

"I am not quite sure," Ellison remarked with a little grimace, "whether I want to speak to you or not! What on earth has kindled the destructive spirit in you to such an extent? Every one is talking of your attack upon the New Theatre!"

"I was sent," Matravers answered, "with a free hand to write an honest criticism—and I did it. Istein's work may have some merit, but it is unclean work. It is not fit for the English stage."

"It is exceedingly unlikely," Ellison remarked, "that the English stage will know him any more! No play could survive such an onslaught as yours. I hear that Thorndyke is going to close the theatre."

"If it was opened," Matravers said, "for the purpose of presenting such work as this latest production, the sooner it is closed the better."

Ellison shrugged his shoulders.

"It is a large subject," he said, "and I am not sure that we are of one mind. We will not discuss it. At any rate, I am very sorry for Berenice!"

"I do not think," Matravers said in measured tones, "that you need be sorry for her. With her gifts she will scarcely remain long without an engagement. I trust that she may secure one which will not involve the prostitution of her talent." Ellison laughed shortly. He had an immense admiration for Matravers, but just at present he was a little out of temper with him.

"You admit her talent, then?" he remarked. "I am glad of that!"

"I am not sure," Matravers said, "that talent is the proper word to use. One might almost call it genius."

Ellison was considerably mollified.

"I am glad to hear you say so," he declared. "At the same time I am afraid her position will be rather an awkward one. She will lose some money by the closing of the theatre, and I don't exactly see what London house is open for her just at present. These actor-managers are all so clannish, and they have their own women."

"I am sorry," Matravers said thoughtfully; "at the same time I cannot believe that she will remain very long undiscovered! Good afternoon! I am forgetting that I have some writing to do."

Matravers walked slowly back to his rooms, filled with a new and fascinating idea which Ellison's words had suddenly suggested to him. If it was true that his pen had done her this ill turn, did he not owe her some reparation? It would be a very pleasant way to pay his debt and a very simple one. By the time he had reached his destination the idea had taken definite hold of him.

For several hours he worked at the revision of a certain manuscript, polishing and remodelling with infinite care and pains. Not even content with the correct and tasteful arrangement of his sentences, he read them over to himself aloud, lest by any chance there should have crept into them some trick of alliteration, or juxtaposition of words not entirely musical. In his work he gained, or seemed to gain, a complete absorption. The cloudy disquiet of the last few hours appeared to have passed away,—to have been, indeed, only a fugitive and transitory thing.

At half-past four his servant brought in a small tea-equipage—a silver tray, with an old blue Worcester teapot and cup, and a quaintly cut glass cream-jug. He made his tea, and drank it with his pen still in his hand. He had scarcely turned back to his work, before the same servant re-entered carrying a frock coat, an immaculately brushed silk hat, and a fresh bunch of Neapolitan violets. For a moment Matravers hesitated; then he laid down his pen, changed his coat, and once more passed out into the streets, more brilliant than ever now with the afternoon sunshine. He joined the throng of people leisurely making their way towards the Park!

FOR nearly half an hour he sat in his usual place under the trees, watching with indifferent eyes the constant stream of carriages passing along the drive. It seemed to him only a few hours since he had sat there before, almost in the same spot, a solitary figure in the cold, grey twilight, yet watching then, even as he was watching now, for that small victoria with its single occupant whose soft dark eyes had met his so often with a frank curiosity which she had never troubled to conceal. Something of that same perturbation of spirit which had driven him then out into the dawn-lit streets, was upon him once more, only with a very real and tangible difference. The grey half-lights, the ghostly shadows, and the faint wind sounding in the tree-tops like the rising and falling of a midnight sea upon some lonely shore, had given to his early morning dreams an indefiniteness which they could scarcely hope to possess now. He himself was a living unit of this gay and brilliant world, whose conversation and light laughter filled the sunlit air around him, whose skirts were brushing against his knees, and whose jargon fell upon his ears with a familiar and a kindly sound. There was no possibility here for such a wave of passion,—he could call it nothing else,—as had swept through him, when he had first read that brief message from the woman, who had already become something of a disturbing element in his seemly life. Yet under a calm exterior he was conscious of a distinct tremor of excitement when her carriage drew up within a few feet of him, and obeying her mute but smiling command, he rose and offered his hand as she stepped out on to the path.

"This," she remarked, resting her daintily gloved fingers for a moment in his, "is the beginning of a new order of things. Do you realize that only the day before yesterday we passed one another here with a polite stare?"

"I remember it," he answered, "perfectly. Long may the new order last."

"But it is not going to last long—with me at any rate," she said, laughing. "Don't you know that I am almost ruined? Mr. Thorndyke is going to close the theatre. He says that we have been losing money every week. I shall have to sell my horses, and go and live in the suburbs."

"I hope," he said fervently, "that you will not find it so bad as that."

"Of course," she remarked, "you know that yours is the hand which has given us our death-blow. I have just read your notice. It is a brilliant piece of satirical writing, of course, but need you have been quite so severe? Don't you regret your handiwork a little?"

"I cannot," he answered deliberately. "On the contrary, I feel that I have done you a service. If you do not agree with me to-day, the time will certainly come when you will do so. You have a gift which delighted me: you are really an actress; you are one of very few."

"That is a kind speech," she answered; "but even if there is truth in it, I am as yet quite unrecognized. There is no other theatre open to me; you and I look upon Istein and his work from a different point of view; but even if you are right, the part of Herdrine suited me. I was beginning to get some excellent notices. If we could have kept the thing going for only a few weeks longer, I think that I might have established some sort of a reputation."

He sighed.

"A reputation, perhaps," he admitted; "but not of the best order. You do not wish to be known only as the portrayer of unnatural passions, the interpreter of diseased desires. It would be an ephemeral reputation. It might lead you into many strange byways, but it would never help you to rise. Art is above all things catholic, and universal. You may be a perfect Herdrine; but Herdrine herself is but a night weed—a thing of no account. Even you cannot make her natural. She is the puppet of a man's fantasy. She is never a woman."

"I suppose," she said sorrowfully, "that your judgment is the true one. Yet—but we will talk of something else. How strange to be walking here with you!"

Berenice was always a much-observed woman, but to-day she seemed to attract more even than ordinary attention. Her personality, her toilette, which was superb, and her companion, were all alike interesting to the slowly moving throng of men and women amongst whom they were threading their way. The attitude of her sex towards Berenice was in a certain sense a paradox. She was distinctly the most talented and the most original of all the "petticoat apostles," as the very man who was now walking by her side had scornfully described the little band of women writers who were accused of trying to launch upon society a new type of their own sex. Her last novel was flooding all the bookstalls; and if not of the day, was certainly the book of the hour. She herself, known before only as a brilliant journalist writing under a curious nom de plume, had suddenly become one of the most marked figures in London life. Yet she had not gone so far as other writers who had dealt with the same subject. Marriage, she had dared to write, had become the whitewashing of the impure, the sanctifying of the vicious! But she had not added the almost natural corollary,—therefore let there be no marriage. On the contrary, marriage in the ideal she had written of as the most wonderful and the most beautiful thing in life,—only marriage in the ideal did not exist.

She had never posed as a woman with a mission! She formulated nowhere any scheme for the re-organization of those social conditions whose bases she had very eloquently and very trenchantly held to be rotten and impure. She had written as a prophet of woe! She had preached only destruction, and from the first she had left her readers curious as to what sexual system could possibly replace the old. The thing which happened was inevitable. The amazing demand for her book was exactly in inverse proportion to its popularity amongst her sex. The crusade against men was well! Admittedly they were a bad lot, and needed to be told of it. A little self-assertion on behalf of his superior was a thing to be encouraged and applauded. But a crusade against marriage! Berenice must be a most abandoned, as well as a most immoral, woman! No one who even hinted at the doctrine of love without marriage could be altogether respectable. Not that Berenice had ever done that. Still, she had written of marriage,—the usual run of marriages,—from a woman's point of view, as a very hateful thing. What did she require, then, of her sex? To live and die old maids, whilst men became regenerated? It was too absurd. There were a good many curious things said, and it was certainly true, that since she had gone upon the stage her toilette and equipage were unrivalled. Berenice looked into the eyes of the women whom she met day by day, and she read their verdict. But if she suffered, she said not a word to any of it.

They passed out from the glancing shadows of the trees towards the Piccadilly entrance. Here they paused for a moment and stood together looking down the drive. The sunlight seemed to touch with quivering fire the brilliant phantasmagoria. Berenice was serious. Her dark eyes swept down the broad path and her under-lip quivered.

"It is this," she exclaimed, with a slight forward movement of her parasol, "which makes me long for an earthquake. Can one do anything for women like that? They are not the creations of a God; they are the parasitical images of type. Only it is a very small type and a very large reproduction. Why do I say these things to you, I wonder? You are against me, too! But then you are not a woman!"

"I am not against you in your detestation of type," he answered. "The whole world of our sex as well as yours is full of worn-out and effete reproductions of an unworthy model. It is this intolerable sameness which suffocates all thought. One meets it everywhere; the deep melancholy of our days is its fruit. But the children of this generation will never feel it. The taste of life between their teeth will be neither like ashes nor green figs. They are numbed."

She flashed a look almost of anger upon him.

"Yet you have ranged yourself upon their side. When my story first appeared, its fate hung for days in the balance. Women had not made up their minds how to take it. It came into your hands for review. Well! you did not spare it, did you? It was you who turned the scale. Your denunciation became the keynote of popular opinion concerning me. The women for whose sake I had written it, that they might at least strike one blow for freedom, took it with a virtuous shudder from the hands of their daughters. I was pronounced unwholesome and depraved; even my personal character was torn into shreds. How odd it all seems!" she added, with a light, mirthless laugh. "It was you who put into their hands the weapon with which to scourge me. Their trim, self-satisfied little sentences of condemnation are emasculated versions of your judgment. It is you whom I have to thank for the closing of the theatre and the failure of Herdrine,—you who are responsible for the fact that these women look at me with insolence and the men as though I were a courtesan. How strange it must seem to them to see us together—the wolf and the lamb! Well, never mind. Take me somewhere and give me some tea; you owe me that, at least."

They turned and left the park. For a few minutes conversation was impossible, but as soon as they had emerged from the crowd he answered her.

"If I have ever helped any one to believe ill of you," he said slowly, "I am only too happy that they should have the opportunity of seeing us together. You are rather severe on me. I thought then, as I think now, that it is—to put it mildly—impolitic to enter upon a passionate denunciation of such an institution as marriage when any substitute for it must necessarily be another step upon the downward grade. The decadence of self-respect amongst young men, any contrast between their lives and the lives of the women who are brought up to be their wives, is too terribly painful a subject for us to discuss here. Forgive me if I think now, as I have always thought, that it is not a fitting subject for a novelist—certainly not for a woman. I may be prejudiced; yet it was my duty to write as I thought. You must not forget that! So far as your story went, I had nothing but praise for it. There were many chapters which only an artist could have written."

She raised her eyebrows. They had turned into Bond Street now, and were close to their destination.

"You men of letters are so odd," she exclaimed. "What is Art but Truth? and if my book be not true, how can it know anything of art? But never mind! We are talking shop, and I am a little tired of taking life seriously. Here we are! Order me some tea, please, and a chocolate eclair."

He followed her to a tiny round table, and sat down by her side upon the cushioned seat. As he gave his order and looked around the little room, he smiled gravely to himself. It was the first time in his life,—at any rate since his boyhood,—that he had taken a woman into a public room. Decidedly it was a new era for him.

AN incident, which Matravers had found once or twice uppermost in his mind during the last few days, was recalled to him with sudden vividness as he took his seat in an ill-lit, shabbily upholstered box in the second tier of the New Theatre. He seemed almost to hear again the echoes of that despairing cry which had rung out so plaintively across the desert of empty benches from somewhere amongst the shadows of the auditorium. Several times during the performance he had glanced up in the same direction; once he had almost fancied he could see a solitary, bent figure sitting rigid and motionless in the first row of the amphitheatre. No man was possessed of a smaller share of curiosity in the ordinary sense of the word than Matravers; but the thought that this might be the same man come again to witness a play which had appealed to him before with such peculiar potency, interested him curiously. At the close of the second act he left his seat, and, after several times losing his way, found himself in the little narrow space behind the amphitheatre. Leaning over the partition, and looking downwards, he had a good view of the man who sat there quite alone, his head resting upon his hand, his eyes fixed steadily upon a soiled and crumpled programme, which was spread out carefully before him. Matravers wondered whether there was not in the clumsy figure and awkward pose something vaguely familiar to him.

An attendant of the place standing by his side addressed him respectfully.

"Not much of a house for the last night, sir," he remarked.

Matravers agreed, and moved his head downwards towards the solitary figure.

"There is one man, at least," he said, "who finds the play interesting."

The attendant smiled.

"I am afraid that the gentleman is a little bit 'hoff,' sir. He seems half silly to talk to. He's a queer sort, anyway. Comes here every blessed night, and in the same place. Never misses. Once he came sixpence short, and there was a rare fuss. They wouldn't let him in, and he wouldn't go away. I lent it him at last."

"Did he pay you back?" Matravers asked.

"The very next night; never had to ask him, either. There goes the bell, sir. Curtain up in two minutes."

The subject of their conversation had not once turned his head or moved towards them. Matravers, conscious that he was not likely to do so, returned to his seat just as the curtain rose upon the last act. The play, grim, pessimistic, yet lifted every now and then to a higher level by strange flashes of genius on the part of the woman, dragged wearily along to an end. The echoes of her last speech died away; she looked at him across the footlights, her dark eyes soft with many regrets, which, consciously or not, spoke to him also of reproach. The curtain descended, and her hands fell to her side. It was the end, and it was failure!

Matravers, making his way more hurriedly than usual from the house, hoped to gain another glimpse of the man who had remained the solitary tenant of the round of empty seats. But he was too late. The man and the audience had melted away in a thin little stream. Matravers stood on the kerbstone hesitating. He had not meant to go behind to-night. He had a feeling that she must be regarding him at that moment as the executioner of her ambitions. Besides, she was going on to a reception; she would only be in a hurry. Nevertheless, he made his way round to the stage door. He would at least have a glimpse of her. But as he turned the corner, she was already stepping into her carriage. He paused, and simultaneously with her disappearance he realized that he was not the only one who had found his way to the narrow street to see the last of Berenice. A man was standing upon the opposite pavement a little way from the carriage, yet at such an angle that a faint, yellow light shone upon what was visible of his pale face. He had watched her come out, and was gazing now fixedly at the window of her brougham. Matravers knew in a moment that this was the man whom he had seen sitting alone in the amphitheatre; and almost without any definite idea as to his purpose, he crossed the street towards him. The man, hearing his footstep, looked up with a sudden start; then, without a second's hesitation, he turned and hurried off. Matravers still followed him. The man heard his footsteps, and turned round, then, with a little moan, he started running, his shoulders bent, his head forward. Matravers halted at once. The man plunged into the shadows, and was lost amongst the stream of people pouring forth from the doors of the Strand theatres.

At her door an hour later Berenice saw the outline of a figure now become very familiar to her, and Matravers, who had been leaving a box of roses, whose creamy pink-and-white blossoms, mingled together in a neighbouring flower-shop, had pleased his fancy, heard his name called softly across the pavement. He turned, and saw Berenice stepping from her carriage. With an old-fashioned courtesy, which always sat well upon him, he offered her his arm.

"I thought that you were to be late," he said, looking down at her with a shade of anxiety in his clear, grave face. "Was not this Lady Truton's night?"

She nodded.

"Yes; don't talk to me—just yet. I am upset! Come in and sit with me!"

He hesitated. With a scrupulous delicacy, which sometimes almost irritated her, he had invariably refrained from paying her visits so late as this. But to-night was different! Her fingers were clasping his arm,—and she was in trouble. He suffered himself to be led up the stairs into her little room.

"Some coffee for two," she told her woman. "You can go to bed then! I shall not want you again!"

She threw herself into an empty chair, and loosened the silk ribbons of her opera cloak.

"Do you mind opening the window?" she asked. "It is stifling in here. I can scarcely breathe!"

He threw it wide open, and wheeled her chair up to it. The glare from the West End lit up the dark sky. The silence of the little room and the empty street below, seemed deepened by that faint, far-away roar from the pandemonium of pleasure. A light from the opposite side of the way,—or was it the rising moon behind the dark houses?—gleamed upon her white throat, and in her soft, dim eyes. She lay quite still, looking into vacancy. Her hand hung over the side of the chair nearest to him. Half unconsciously he took it up and stroked it soothingly. The tears gushed from her eyes. At his kindly touch her over-wrought feelings gave way. Her fingers closed spasmodically upon his.

He said nothing. The time had passed when words were necessary between them. They were near enough to one another now to understand the value of silence. But those few moments seemed to him for ever like a landmark in his life. A new relation was born between them in the passionate intensity of that deep quietness.

He watched her bosom cease to heave, and the dimness pass from her eyes. Then he took up the box which he had been carrying, and emptied the pink-and-white blossoms into her lap. She stooped down and buried her face in them. Their faint, delicate perfume seemed to fill the room.

"You are very good," she said abruptly. "Thank God that there is some one who is good to me!"

The coffee was in the room, and Berenice threw off her cloak and brought it to him. A fit of restlessness seemed to have followed upon her moment of weakness. She began walking with quick, uneven steps up and down the room. Matravers forgot to drink his coffee. He was watching her with a curious sense of emotional excitement. The little chamber was full of half lights and shadows, and there seemed to him something almost unearthly about this woman with her soft grey gown and marble face. He was stirred by her presence in a new way. The rustle of her silken skirts as she swept in and out of the dim light, the delicate whiteness of her arms and throat, the flashing of a single diamond in her dark coiled hair,—these seemed trivial things enough, yet they were yielding him a new and mysterious pleasure. For the first time his sense of her beauty was fully aroused. Every now and then he caught faint glimpses of her face. It was like the face of a new woman to him. There was some tender and wonderful change there, which he could not understand, and yet which seemed to strike some responsive chord in his own emotions. Instinctively he felt that she was passing into a new phase of life. Surely, he, too, was walking hand and hand with her through the shadows! The touch of her interlaced fingers had burned his flesh.

Presently she came and sat down beside him.

"Forgive me!" she murmured. "It does me so much good to have you here. I am very foolish!"

"Tell me about it!"

She frowned very slightly, and looked away at a star.

"It is nothing! It is beginning to seem less than nothing! I have written a book for women, for the sake of women, because my heart ached for their sufferings, and because I too have felt the fire. I wonder whether it was really an evil book," she added, still looking away from him at that single star in the dark sky. "People say so! The newspapers say so! Yet it was a true book! I wrote it from my soul,—I wrote it with my own blood. I have not been a good woman, but I have been a pure woman! When I wrote it, I was lonely; I have always been lonely. But I thought, now I shall know what it is like to have friends. Many women will understand that I have suffered in doing this thing for their sakes! For it was my own life which I lay bare, my own life, my own sufferings, my own agony! I thought, they will come to me and they will thank me for it! I shall have sympathy and I shall have friends.... And now my book is written, and I am wiser. I know now that woman does not want her freedom! Though they drag her down into hell, the chains of her slavery have grown around her heart and have become precious to her! Tell me, are those pure women who willingly give their souls and their bodies in marriage to men who have sinned and who will sin again? They do it without disguise, without shame, for position, or for freedom, or for money! yet there are other women whom they call courtesans, and from whose touch they snatch away the hem of their skirts in horror! Oh, it is terrible! There can be no corruption worse than this in hell!"

"Yours has been the common disappointment of all reformers," he said gravely. "Gratitude is the rarest tribute the world ever offers to those who have laboured to cleanse it. When you are a little older you will have learnt your lesson. But it is always very hard to learn.... Tell me about to-night!"

She raised her head a little. A faint spot of colour stained her cheek.

"There was one woman who praised me, who came to see me, and sent me cards to go to her house. To-night I went. Foolishly I had hoped a good deal from it! I did not like Lady Truton herself, but I hoped that I should meet other women there who would be different! It was a new experience to me to be going amongst my own sex. I was like a child going to her first party. I was quite excited, almost nervous. I had a little dream,—there would be some women there—one would be enough—with whom I might be friends, and it would make life very different to me to have even one woman friend. But they were all horrid. They were vulgar, and one woman, she took me on one side and praised my book. She agreed, she said, with every word in it! She had found out that her husband had a mistress,—some chorus-girl,—and she was repaying him in his own coin. She too had a lover—and for every infidelity of his she was repaying him in this manner. She dared to assume that I—I should approve of her conduct; she asked me to go and see her! My God! it was hideous."

Matravers laid his hand upon hers, and leaned forward in his chair.

"Lady Truton's was the very worst house you could have gone to," he said gently. "You must not be too discouraged all at once. The women of her set, thank God, are not in the least typical Englishwomen. They are fast and silly,—a few, I am afraid, worse. They make use of the free discussions in these days of the relations between our sexes, to excuse grotesque extravagances in dress and habits which society ought never to pardon. Do not let their judgments or their misinterpretations trouble you! You are as far above them, Berenice, as that little star is from us."

"I do not pretend to be anything but a woman," she said, bending her head, "and to stand alone always is very hard."

"It is very hard for a man! It must be very much harder for a woman. But, Berenice, you would not call yourself absolutely friendless!"

She raised her head for a moment. Her dark eyes were wonderfully soft.

"Who is there that cares?" she murmured.