RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

"A Sleeping Memory," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1907

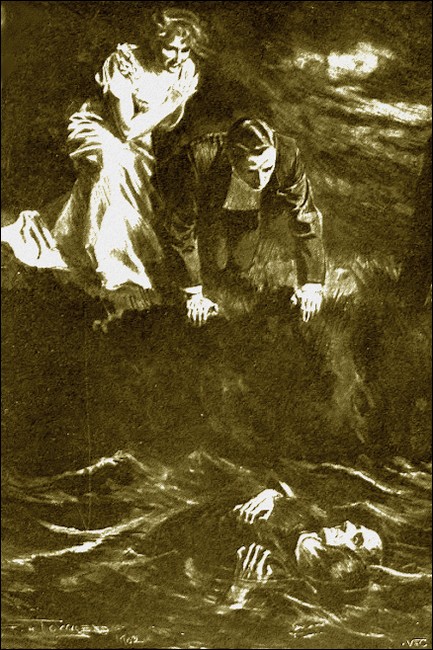

Frontispiece

´

´

"Kiss me," he said, "and I will do even as Ulric would have done."

The fringe of a city fog was hanging about the Edgware Road. The sky—such of it as could be seen—was heavy with gray clouds, the pavements were wet and sloppy with recent rains. The broad thoroughfare was almost deserted. The few foot passengers hurried along with upturned collars and dripping umbrellas. It was a bad afternoon for the shops. Before one of the largest two girls were standing together.

It was the London headquarters of a wholesale mantle and jacket maker, whose name loomed large from the hoardings of half the great towns in England. Behind the plate-glass windows covering the immaculate shapes of many wooden dummies were a goodly collection of ready-made garments, whose peculiar qualities, bravely set out in thick black letters, upon long strips of cardboard, might well have exhausted the whole stock of feminine adjectives. A tweed cape with a hood and a cunningly displayed plaid lining advertised itself as the "Ranelagh Golf Cape," a more gorgeous garment in the background appealed to possible purchasers as the "Countess" mantle, and gave modest reassurance as to the quality of its trimming and its Parisian extraction.

The customers of the establishment were obviously of sporting tastes, and addicted to the diversions of the well-to-do. There were yachting jackets and shooting capes, driving cloaks, and—in a little window all to themselves—opera wraps! Everything was marvellously cheap. There were notes of exclamation following the prices. There were rows of electric lights to enhance the brilliancy of jet trimmings and steel buttons. Truly the place should have been a feminine Paradise.

Yet of all this magnificence there were but two spectators—two girls huddled together under one umbrella. The younger, large-eyed, anaemic, untidy, looked and spoke of what she saw with eager and strenuous toleration—a toleration which at times was merged into enthusiasm. Her companion, who was taller, and who held herself with a distinction which was oddly at variance with her shabby clothes, never attempted to conceal her contempt for this tinselly array of self-styled Paris models and cheap reproductions from the inner world of fashion. And indeed she seemed scarcely the sort of person for ready-made garments.

The younger girl's interest was apparently impersonal. She was essaying the part of a feminine Mephistopheles.

"I say, Eleanor, I think that one's quite stunning," she declared, pointing suddenly at one of the most atrocious of the models. "It's smart, ain't it? There was a lady came to the shop yesterday wearing one just like it. I declare you couldn't tell 'em apart. She was a lady too—really. She came in a carriage, and she had a little dog, and a real gold muff-chain, with funny little stones set in it—not one of them imitation things. It's cheap, too, only twenty-seven and elevenpence. Come in and try it on. I'll ask for it if you like!"

The girl glanced at the jacket and shivered. She made an effort to move away from the shop, but her companion's arm restrained her.

"Why, you haven't even looked at it!" she protested. "What a one you are to come shopping! Look at those steel ornaments. I call it most ladylike!"

"It is absolutely hideous, Ada," the other declared. "I would not put the thing on. Come away. There is nothing here. I am weary of looking at all this ugliness. Let us go and have some tea somewhere—and sit down!"

But Ada declined to move. She ignored her companion's weary gesture, and continued her expostulations. Her high-pitched Cockney voice sounded strangely after the other girl's soft speech and correct enunciation.

"Now, Eleanor, you must be reasonable," she declared vigorously. "It's all rubbish to be turning your nose up at everything just because it ain't exactly what you've been used to. A jacket you must have, and you cannot expect to go to Redfern with something under thirty shillings."

"I can make this do—a little longer."

"You can't! It's threadbare, and you'll catch your death of cold. This place is as good as any. If you don't like what's in the window, let's go in and see if they've got anything else. I know the young gentleman who's head-salesman here, and he won't mind a bit of trouble—especially when he sees you. I think I can get a bit off the price too. Come along!"

Her companion shook herself free from the arm which was urging her inside. A sudden light flashed in her eyes, her lips quivered. Notwithstanding her worn clothes, her ill-shapen hat, and the hideous white glare in which they stood, one saw immediately that she was beautiful. The slight sullenness which in repose marred her features was gone. The faint flush which crept through the unnatural pallor of her cheeks restored her coloring, one realized the elusive blue shade of her eyes, the many coils of soft brown hair arranged with a grace which contrasted strangely with the worn hat and veil. She grew younger, too, with that little burst of feeling, the soft delicacy of her skin, the lingering girlishness of her figure asserted themselves. But she was very angry.

"You are blind, Ada!" she exclaimed passionately. "You see nothing! You understand nothing."

"Mercy me! I don't know so much about that!" Ada retorted, half indignant.

"Oh, don't be foolish! You're better off. Thank God for it—and come along."

"I understand that you'll catch your death o' cold in this wind with little more than a rag around you," Ada declared vigorously. "I've twice as much on as you, and I'm almost perished. I'd sooner have the fog than this. It's enough to kill you!"

The other girl shrugged her shoulders slightly.

"What if it does! Is life such a beautiful gift then to you and to me—to the thousands who are like us?"

"I'd sooner live than die, anyway," Ada declared bluntly. "Bearmain's is a bit rough, perhaps, but there's plenty of fun to be had if you set the right way about it."

The other girl smiled faintly.

"I am afraid," she said, "that I shall never find the right way. I should be glad to die to-day, tomorrow, this moment! Come, if my threadbare rags will take me to another world that disposes once and for all of the jacket question, I'll hug them and welcome."

Ada abandoned the subject with a little gesture of impatience. She attended church once every Sunday, and it sounded irreverent to her.

"Let's go and have some tea, then," she suggested. "You're tired now, and no wonder. Perhaps you'll feel more heart afterwards."

The girl whom she had called Eleanor laughed shortly, but did not move. She, who a few minutes ago had tried to drag her companion from the spot, seemed to find now some evil fascination in those long rows of resplendent garments.

"Look at them, Ada," she exclaimed bitterly. "They are for you and for me, and for the thousands like us. They are ugly, they are cheap, they are pretentious. That is what life is for us. And we can't escape. We are shut in on every side. It is horrible."

Her lips quivered—there was a break in her voice. Ada looked into her face with vague, wistful sympathy. She was sorry, but she did not understand. She looked once more at the jackets in the window.

"I can't see that the things are so dreadful—for the price," she said. "You haven't been used to ready-made clothes, I know, but after all I don't see where the difference comes in. I always look at it like this—if you can't afford the one thing you must have the other. That's reasonable, isn't it now?"

There was a moment's silence. Then both girls became suddenly aware that a man was standing upon the pavement only a few feet away, gazing through the shop windows with an absorption which was obviously simulated. He was in a position to overhear their conversation—he had already, in all probability, overheard some part of it. Without a glance in his direction the two girls turned away. The man, after a moment's hesitation, followed them.

The older girl drew a long breath of relief.

"Do you know, Ada," she said, "I think if I had stood much longer before that window I should have cried. Is there anything more depressing than ugliness?"

Ada sighed.

"I don't see that you're much nearer getting your jacket," she said, "and that's what we started out, so early for."

Her companion laughed softly.

"Never mind," she said. "You needn't worry any more about that. I have quite made up my mind. I am going to buy some cloth and make it myself."

"There can't be much cut about it," Ada remarked doubtfully. "A jacket's just one of those things I don't see how one can make oneself. So much depends upon the style."

Again her companion laughed, and the man behind seemed to find it pleasant to hear, for he quickened his pace and drew a little nearer to them.

"You must wait and see it before you criticise, Ada," she said. "You shall help me to choose the material to-morrow."

Ada's face brightened.

"You'll get it at Bearmain's!" she exclaimed. "Well, Henry shall see that the price is all right I'll speak to him myself."

The girl nodded. She dismissed the subject of the jacket with manifest relief.

"Now for some tea," she said. "No, not at an A.B.C. to-day. I am so weary of those thick cups and saucers, and the endless chatter. I am going to take you somewhere else."

"You mustn't be extravagant," Ada protested timidly. "I think an A.B.C. is really very nice, and it's a good bit better than Bearmain's, anyhow. You're always for spending all your money directly you get it."

Her companion smiled. The accusation was by no means unfamiliar to her.

"Do you know," she said, "what I have often been tempted to do? To sell all my few remaining belongings, scrape together every penny I have, and for one long day—to live!"

Ada looked up at her perplexed.

"Isn't that what we're doing all the time?" she asked timidly.

The elder girl laughed tolerantly, but with a note of contempt underlying her mirth.

"You foolish child! What do we know of life, you and I, who spend ten hours of every day behind a counter, the servants of every impertinent woman who wants a yard of calico. From the moment we wake to the moment when the bell rings and we are packed off like sheep to bed, we are slaves. We have to do it to eat and drink!—but it is not life, it is not even freedom. You don't understand. Always be thankful that you do not!"

"Tell me what you would do in that one day?"

The girl was suddenly thoughtful. Her eyes gleamed as though even the thought gave her pleasure.

"I will tell you," she said. "I would go into Bond Street and I would buy clothes—just for one day—everything. I would know the feel of cambric and lace, and I would buy perfumes and flowers. Then just a simple walking dress and a pretty hat—and oh! fancy for one day being able to wear gloves and boots like those other women wear. Then I would go to one of those old-fashioned hotels somewhere near Berkeley Square, have a maid prepare a bath for me, and change all my clothes slowly, and burn everything which reminded me of the Edgware Road! I would go out to lunch then to one of the best restaurants—Prince's, I think—and I would buy myself a great bunch of fragrant Neapolitan violets, and imagine that some one had sent them to me. And I would order the sort of dishes that make eating artistic, and I would drink wine, soft, white wine, with the flavor of Moselle grapes, and afterwards—"

"Yes, afterwards?" Ada interrupted breathlessly.

The girl's face was sad once more. In her eyes was the old hunger, her voice became almost a whisper.

"Afterwards would be beautiful too. I would take the train to a tiny little village in Surrey which few people know about—it is quite out of the world. When you leave the station you step into a narrow, country lane with tall hedges full of birds, and you never meet any one except sometimes an old farm laborer. Then you climb and climb and climb, and at last you come to a very steep hill. The lane becomes a footpath, and at the top there is a little gate leading into a deep grove of pine trees—oh, you don't know what the odor of pines is like, Ada, when the sun is hot upon them. Then I should lie down—pine cones are softer than any mattress—and I think that the rest of that moment would be worth all these months of slavery. There are wild roses in the hedges with great pink blossoms, and the perfume is so faint and yet so perfect—and honeysuckle. You have been in the country sometimes. You know what the scent of honeysuckle is like. And the birds—it is wonderful to hear them sing; there is music, too, in the air when the west wind sweeps through the pine trees!"

"And—afterwards?" Ada asked again, in a low, fearful tone.

The girl looked downwards into her companion's rapt face, and smiled gravely.

"Afterwards I should lie quite still watching the white clouds pass across the sky—watching and listening! I think that all my weariness and bad temper would pass away from me then because the old life was finished."

"Finished?"

"Yes! After a day like that I could never come back again. If ever I should escape, Ada, if it were only for twenty-four hours, I should never come back again...One gets used even to slavery. I suppose it is that which keeps me at Bearmain's."

"But you must live! You do not mean—"

"That is what I do mean!"

"You would pray first?" the younger girl asked, in an awed whisper.

"I should speak to God—out there. Here I cannot even believe that there is a God. I should ask Him to look at the two worlds which He has made, and I would ask Him how, after a single day in the one, it were possible for such a creature as He made me to go back to the other. I would ask Him to show me where was the justice of those two worlds side by side, Heaven and Hell, yet even here in London so far apart that you and I may beat our hearts in vain before the bars. That's the cruel part, Ada. The other world is always there. You can see into it. It isn't unworthiness that keeps you out. It is chance!"

They stopped short before the door of a tiny restaurant. From inside came the glow of rose-shaded lamps, and a commissionaire looked somewhat critically at the two girls. They hesitated for a moment, acutely conscious of his disapproving glance, his burly figure filled the doorway. Suddenly the man who had been following them stood by their side. He addressed the elder girl, and his manner and tone were quietly deferential.

"The bars of the other world," he said, "are perhaps not so immovable as they seem to you just now. I must ask your forgiveness for having accidentally overheard a portion of your conversation."

The girl eyed him coldly, but without embarrassment.

"I do not think," she said, "that I have the pleasure of knowing you. Perhaps it is my friend with whom you are acquainted."

He appeared in nowise disconcerted at her steady gaze of inquiry, at the shoulder already half turned against him.

"I know," he said, "that I am a transgressor. I am a stranger both to yourself and to your friend. Yet I am going to ask you to do me the honor of having tea with me. I am almost old enough to be your father, and I shall take the liberty of introducing myself as soon as I can get at my card-case. I beg that you will accept my invitation."

Ada was already on the point of moving away. She had no doubt whatever as to what her companion's answer would be. They had been accosted before by boulevarders, young and old, and the departure of even the hardiest had been an abject thing to witness. But this was a day of singular happenings. The few scathing words which should surely have been spoken remained unsaid. Ada looked up, amazed at the silence. The man and the girl were gazing steadfastly at one another. Something was passing between them beyond her comprehension, something which troubled her vaguely as savoring of a world of greater things than any which she had account of. She was a shop-girl, pure and simple, one of her class in spirit as well as fact, with all the limitations of a stereotyped conventionality, a puny imagination, and a point of view which left her feet planted upon a molehill. Yet even she recognized that this was an incident, differing in some vague manner from any other which had ever befallen them. The man was no more a boulevarder than Eleanor was flighty. She waited breathlessly for what might happen.

"You are very kind," Eleanor said quietly; "we were just thinking of having some tea."

The commissionaire, to whom their meeting had presented no unusual features, stepped on one side promptly now, and touched his hat to their escort. The door was swung open before them. Ada resigned herself to an amazed but cheerful compliance. They entered the tea-rooms together!

Inside the little place seemed to the two girls unexpectedly bright and cosy. In the centre of the round table to which their escort led them was a great bunch of scarlet flowers, and the perfume of hyacinths was like a breath of Springtime. The tea appointments were dainty, the attendants deft and smiling. From an inner room came the soft music of violins. The rose-shaded lights were kind to the girls' clothes, and even Ada, who showed some signs of an embarrassment which was shared in no degree by her companion, looked about her with mingled pleasure and curiosity.

"I'm glad we thought of coming here, Eleanor," she whispered. "Isn't the music lovely, and what dear little cakes."

Eleanor, who had loosened her jacket and was leaning back in her cushioned seat, gave a little sigh of satisfaction.

"It is so deliciously warm," she said, "and after that terrible A.B.C. it is like Paradise! May I have chocolate, please, instead of tea."

He had returned from finding a place for his hat, and taking a chair opposite to them gave an order to the smartly dressed waitress. He smiled across at them pleasantly.

"And now!" he said, "for the conventionalities. I have a card-case somewhere, I know."

He unbuttoned his coat and began a search for it. Meanwhile the two girls surveyed him with covert but widely different curiosity. If indeed he was old enough to be the father of either of them, he bore his years remarkably well. He might possibly have been thirty-five, it was hard to believe him a day older. He was clean-shaven, with hard, well-cut features, smooth dark hair, and wonderfully clear gray eyes. He was dressed quietly, but fashionably, and with an attention to detail which the elder girl recognized at once and appreciated. He did not look in the least the sort of man to care about adventures or the consorting with those who were his social inferiors. He produced a card from a tiny silver card-case and handed it to Eleanor.

"You will find my name there," he said. "I live in Hans Crescent. Now you must tell me, please, how I may call you—and your friend."

"My name is Eleanor Surtoes," she said, "and my friend's Ada Smart. We are employed at a drapery establishment in the Edgware Road."

He bowed gravely. It was impossible to tell from his face whether he felt any surprise. Ada, who felt that such candor was wholly unnecessary, kicked her friend under the table without effect.

"The conventionalities," he remarked pleasantly, "are satisfied. It only remains for me to thank you for your confidence, and to assure you 'that it will not be misplaced."

"It is the first time," Ada interposed, "that either Miss Surtoes or myself have ever done such a thing as this—isn't it, Eleanor?"

She nodded.

"I do not understand," she remarked, "why you spoke to us—any more than I can understand our coming in here with you."

"I spoke to you," he said, "because I overheard some part of your conversation, and I was most anxious to make your acquaintance."

Eleanor flushed slightly.

"Your hearing," she said dryly, "must be remarkably acute."

"I am not going to offer any more apologies," he assured her. "I felt sure that you would acquit me of impertinence. I don't know why, but I was quite confident."

"You are evidently," she murmured, "not afflicted with nervousness."

"In my younger days," he answered, "I was brought up in a profession which does not recognize nerves."

"And now?"

"I was meant to be a physician, but I have never practised."

She nodded.

"Well," she said, "you overheard some of our conversation. Why did that interest you personally?" He helped himself to some more sugar, and stirred his tea thoughtfully.

"I will tell you presently," he said. "Let me assure you at least that I am not a vulgarly curious person, a libertine, or a philanthropist."

Eleanor sipped her chocolate and leaned back in her chair with an air of lazy content. The pleasant warmth of the place and the sound of his cultivated voice engaged now in sustaining a perfectly effortless conversation with Ada were very soothing to her after the cold, wet streets, and her companion's good-natured but irritating chatter. Ada, though such adventures were far less foreign to her, was by no means wholly at her ease. She was conscious of being surrounded by better-dressed people of a different station in life, who glanced now and then curiously at the two girls. More than once their escort was saluted by friends, whose greetings he returned with easy indifference. Eleanor, watching him more closely than he was aware of, could not detect the slightest signs of disquietude on his part even when two ladies paused for a moment to speak to him, and scarcely troubled to conceal their amazement when they realized that the two girls were his guests. He met Eleanor's scrutinizing gaze with an answering flash of comprehension.

"My friends," he remarked, "have a right to look a little surprised to see me here with you. I do not frequent such places, and I believe because I do not as a rule find much to interest me in the society of your sex that I am considered to be a hardened misogynist. It is one of the penalties of bachelordom."

"You can easily escape from it!" she reminded him.

He shook his head.

"Marriage," he said, "is one of those experiments which, properly considered, is no experiment at all The finality of the thing is so overwhelming."

She was suddenly thoughtful.

"I am a very persistent person, I am afraid," she said, looking up at him, "but I should like to know your real reason for speaking to us. It is a puzzle to me! I know quite well that you are not one of those who amuse themselves with such adventures, or we should not be here. At the same time, I do not think you were wholly disinterested. You haven't in the least a sympathetic appearance. You had a definite reason, I am sure. What was it?"

The man was Sphinx-like. There was nothing to be read from his face.

"You are quite right," he said. "I have never spoken to a woman before without a formal introduction, and only then when I have been compelled to. I am going to be ungallant enough to admit that your sex does not as a rule particularly attract me. I have other and very strong interests in my life."

She nodded.

"I imagined so. Hence my curiosity. Forgive me if I remind you that we must go in a few minutes, and you have not yet gratified it."

"That is very reasonable," he said. "I will satisfy it if I can to some extent. I think I told you that I started life as a physician. I still devote a good deal of time to one branch of the profession, although my studies are purely private."

"I am glad you do something," she said, smiling. "Idleness is a woman's natural state, but for a man it is demoralizing."

He nodded.

"Quite right! Well, it has always seemed to me, although few people will admit it, that my profession is one which brings any one engaged in it into a very close and actual sympathy with one's fellow-creatures generally. When I say sympathy do not misunderstand me. I make no false claims to being a sympathetic person. I should say perhaps understanding."

Ada sat listening with wide-open eyes. Her private opinion was that their escort was a little mad. Eleanor was puzzled but interested.

"Well!"

"I heard you speak, and I knew that your words came from your heart. There was the ring of absolute truth about them. I do not know by what accident you occupy your present position, or what your chances may be of escaping from it. I take it for granted that your own estimate of it is a faithful one. If so, you are in a hopeless state. Your life must be intolerable!"

"My life," she murmured, "is worse than intolerable."

He assented cheerfully.

"I was privileged," he continued, "owing to my exceptional hearing, to become still further your involuntary confidant. You spoke of a certain visionary day, of a long, sweet draught from the cup of life, and afterwards—oblivion, what men call death."

His is eyes held hers—they were bright with a certain steely radiance. She felt her heart beating fast, the music in the room beyond seemed to her to come from a far distance.

"I gathered, of course," he continued, "that you were a pagan, pure and simple. You do not possess what these silly women call soul. You are anxious, fiercely anxious to make the best of the only life which we can possibly know anything about. I heard you speak, and the human note was strong in all that you said. It occurred to me at once that you were the woman for whom I had been seeking."

"You are very mysterious," she said slowly. "I do not remember now all that I said, but I am quite sure that there was not a single word which I did not mean."

"You spoke," he declared, "as one in extremity. You spoke as a woman who had none of the ordinary fear of death. You spoke as one who would dare great things to pass from the evil place in which fate has set you into the world beautiful."

"I am afraid of death," she said, her eyes bright, her voice tremulous with a sudden passion, "only because I do not want to die before I have lived."

He nodded.

"There are many like that," he said, "but without the courage to own it. May I be quite frank with you? It may save you from embarrassment later on. I followed—not you but the unit of humanity who felt as you felt. Personally I have interests in my life so absorbing that your sex for many years have been little else save shadows to me. That may sound ungallant, but it will help you to understand."

She smiled.

"It may," she admitted. "At present I am all at sea."

"I am going to be a little more explicit at any rate," he assured her. "I believe that in you I have found a person whose life is wholly distasteful to them, who would welcome oblivion, and who has no absolute fear of death."

"I fear death," she answered firmly "less than I fear to-morrow and the whole future of to-morrows! Sometimes I see worse things than death before me!"

"You have no friends?" he asked.

"None!"

"No hope of deliverance?"

"None!"

"I do not wish," he said, "to seem impertinent or inquisitive. Yet it is apparent that you are not of the class which claims you now. You may have had family troubles which will right themselves."

"I have no family," she answered. "My father and mother are both dead. I am alone in the world, and there is no living person to whom I may look for help."

He glanced towards Ada, whose impatience was manifest.

"Your companion," he remarked, "looks at me as though I were a madman. I am afraid that she is in a hurry."

"She can wait," Eleanor answered curtly. "Go on!"

"Let me put an extreme case to you, then," he said, lowering his voice a little. "Supposing that you were suddenly removed from your present life, would there be any one who would have the right to search for you?"

"Not a soul!" she answered.

He nodded thoughtfully. A certain satisfaction was apparent in his pale, set face. Ada eyed him with deep distrust. To her the whole episode was capable of but one explanation. The man was plotting to get Eleanor into his power, and she was just in the mood to be an easy victim. She could scarcely keep her indignation from breaking out.

"Eleanor," she said, "it is time we were going. We are very much obliged' to you, sir, for the tea, but when Eleanor says that she has no friends she says what isn't true, and she knows it. If harm came to her I'd never rest till I'd found out all about it."

He smiled at her good-naturedly.

"I am afraid," he said, "that you have misunderstood me a little. I was simply putting a supposititious case, which is not in the least likely to happen."

He rose to his feet, and accepted his hat from an attendant.

"Listen," he said. "If you are what you seem to be, and if you have the courage which I believe you to possess, I think that before long I can give you a chance of escape from your present slavery. I want you to reflect once more carefully upon the questions which I have asked you and the answers which you have made."

"They need no further reflection," she said. "All that I have told you I mean. Tell me what you mean by a chance of escape?"

His eyes rested for a moment upon Ada, who stood near watching him suspiciously.

"It is not a matter to be decided upon lightly," he said. "I have your address, and I will write to you before long."

He held out his hand.

"I must thank you very much," he said, "for your society—and for your confidence. Good afternoon!"

He parted from them upon the pavement with a pleasant but conventional farewell, and they watched him call a hansom and drive off. Then they looked together at his card which Eleanor had brought out all crushed up in her hand. She straightened it out, and they moved underneath a lamp-post.

"Sir Powers Fiske,

131 Hans Crescent."

"I don't care if he's a hundred times a Sir," Ada exclaimed. "I don't like him. I wish we'd never seen him."

Eleanor said nothing. But she put the card care, fully in her pocket.

Outside, the two girls passed into a street wet with rain, ill-lit, and almost deserted by foot passengers. A cold, damp wind blew in their faces, the change from the perfumed warmth of the brightly-lit tearooms made them shiver as they turned southwards. Ada passed her arm through her companion's, and together they struggled along.

"I wish you would hold the umbrella over yourself," Eleanor said, as they rounded a tempestuous corner. "Your skirt must be wet through."

"I'm all right," Ada declared. "My clothes are thicker than yours. Are you going to let me ask you something, Eleanor?"

"Why not?"

"What made you do it? You're always so particular—snap a fellow's head off almost if he speaks to you. Yet you followed him in there as though you had known him all your life!—and he was a bad 'un! Ugh!"

Eleanor laughed softly and mirthlessly.

"Why do you say that? I thought he was rather interesting."

Ada looked upwards in scornful wonder.

"You ain't so simple as all that, Eleanor, I know. Bother his fine talk, I say. I've met his sort 'before—all the gentlefolk who take the trouble to talk to any of us are the same. A lot of soft-sounding palaver, and as much real wickedness behind it as you'll find in a day's march. Not for me, thank you! Nor for you, Eleanor, eh?"

Again that upward anxious glance. Ada knew that this girl whom chance had made her companion was in a dangerous mood, and she knew, too, that between her and the man who had just left them had existed some sort of subtle sympathy wholly outside her powers of definition which' irritated and alarmed her, but which she was powerless to ignore.

"I am not sure that you judge him rightly," Eleanor answered, "but after all it scarcely matters, does it? I do not suppose that we are either of us likely to see him again."

Ada was visibly relieved.

"I hope to goodness we shan't," she answered heartily. "I ain't nervous as a rule, but he scared me with his strange talk and the way he looked at you. I can't abide people who talk in riddles. Why couldn't he out with what he wanted like a man. I don't think you'd have had much more to say to him then!"

Eleanor looked doubtful.

"I believe now that he was honest," she said. "I can't help it. Yet he was certainly very mysterious. He frightened me, too, a little. Why was he so anxious to know whether I was afraid to die? What did he mean, I wonder?"

"Mean?" Ada gave vent to a contemptuous exclamation. "Mean! Oh, his meaning was plain enough. I've met his sort before, only not quite so barefaced. If ever you were to go near him, Eleanor; you'd find out fast enough. All that fine talk of his was simply rot. There's only one thing such as him could do for you, and only one price to be paid. It's sickening, but it's true."

"I daresay you are right," Eleanor said wearily. "All the same, I can't help feeling that I should like to know more about him. Don't look so horrified, child! Remember that after all I have seen more of the world than you have. I, too, know something of the sort of men of whom you are thinking. I can't class him amongst them. It's quite impossible."

"He's there, all the same, wherever you put him," Ada declared. "I should like to know what else he spoke to us for, and talked to you as though you were the first woman he had seen in the world. He wasn't a boy, you know, looking out for a spree. He heard you talking as though you'd like to chuck ourself away for an old song, and he followed us deliberately."

"We are not going to talk about him any more," Eleanor said firmly. "Perhaps I was foolish, but there is no harm done, and it was a pleasure to hear a gentleman's voice again. Is that six o'clock? Where were you to meet Mr. Johnson?"

"I told them that we should be at the theatre at half-past," Ada answered.

Eleanor stopped short in the middle of the pavement.

"Them! Who?"

There was a moment's awkward silence. Ada had intended to keep that plural to herself until the meeting was actually over. She tightened her grasp upon her companion's arm.

"You mustn't be cross, Eleanor," she begged. "It's a friend of Henry's who's going with us. He's not at Bearmain's. In fact, he's not in our sort of business at all. Henry says he's awful good company, and you know how particular he is."

"I would rather go back, Ada," Eleanor said doubtfully. "I didn't mind you and Mr. Johnson, because of course you would have plenty to talk. about, but I am not in the humor for company."

"Oh, he'll do the talking all right," Ada urged. "He's that sort! You see, as Henry said, three's such an awkward number for getting in. We must go two and two, and you might get with some one ever so horrid, and Henry hates not to have me to talk to while we're waiting."

Eleanor shook her head vigorously.

"It is too bad of you, Ada," she declared. "You know quite well that if you had told me I should not have come. I do not wish to make any fresh acquaintances. I shall go back at once."

Ada's eyes filled with tears.

"You'll do nothing of the sort, Eleanor," she declared. "If you do I shall go with you. Do be sensible for once now, dear. I know that we aren't any of us quite your sort, but you've got to live with us for the present, at any rate, and you might just as well make the best of it. You can't stick in at Bearmain's every night, and you can't walk about the streets by yourself."

Eleanor shook her head.

"You mustn't think me unreasonable, dear," she said, "but I really would rather not come. I know that a third person is in the way, and I told you so when you asked me, but you and Mr. Johnson were so nice about it that I think I was a little over-persuaded. But I certainly am not going with a stranger whom I have never met before, and who probably wouldn't let me pay for my own ticket. Besides—"

"That's just it," Ada interrupted triumphantly. "That's what I wanted to tell you. We shan't any of us have to pay for our tickets. Henry's friend, Mr. Chadwick, who is going with us, is a literary gentleman, who writes for papers, and gets orders. He's got passes for four into the Haymarket, and by waiting an hour or so we shall get into the front row of the pit—every bit as good as the stalls, where all the swells sit. Oh, you must come along, Eleanor. He's quite gentlemanly I'm sure, or Henry wouldn't have took up with him, and if you don't like him, you know, why, you needn't have anything more to do with him afterwards. Come along, there's a dear!"

Eleanor suffered herself to be persuaded. They hurried on to the top' of the Haymarket, where the two young men were awaiting them. Henry was one of the junior shopwalkers at Bearmain's, and as such a person of some consequence. He greeted Ada with levity, and Eleanor, of whom he was secretly a little afraid, with his best floor manner. Afterwards he begged leave to present his friend, Mr. Laurence Chadwick, a young man on a somewhat expansive scale, who wore a seedy frock-coat, trousers much frayed at the edges, and a silk hat with an abnormally large brim. A waistcoat cut unusually low displayed an uninviting amount of white piqué tie, reposing upon a shirt whose cleanliness was ancient history.

"I hope you young ladies won't mind waiting a bit," Mr. Johnson. remarked. "We shall have to stand two and two, you know, like the animals, but there ain't many there yet, and we ought to get in the front row. What do you think, Chadwick, you know all about these places?"

Mr. Chadwick thought that with management it might be done, but proposed an immediate move. A few minutes later, and they were standing in their places upon the pavement. Mr. Chadwick immediately proceeded to count the people in front with a professional air.

"H'm!" he remarked. "There's a front row ahead of us, and four over. However, the doorkeeper's a pal of mine, and he'll see us right. We'll have to judy some one going in."

Eleanor ventured to remark that the second row was almost as good, but Mr. Chadwick shook his head in a superior manner.

"The front row is the place of the 'ouse," he asserted confidently. "You leave it to me, and we'll get there somehow. Got any smokes, Henry?—that is, if Miss Surtoes has no objection."

Miss Surtoes had no objection to anything. So the long hour of waiting commenced. The cigars were doubtful and smelt rank, the rain and wind were a miserable combination. Eleanor's boots, thin and almost worn through, were powerless to withstand the cold dampness of the sloppy pavements. Before half the time had gone by she found herself choking back the sobs. The drippings from an umbrella behind had worn their way through a weak place in her jacket. Her companion's attempts at conversation jarred every moment upon her over-strung nerves. And all the time the indignity of the thing set her quivering with anger. The passers-by eyed them with blended curiosity and contempt, the women from their cabs and carriages going home from their shopping, or on their way to dine, watched them in languid amusement. A couple behind were peeling and eating oranges, a glass flask of spirits was being passed from hand to hand. She sank at last into a sort of torpor, numbed with cold and the acute discomfort of her surroundings. Her companion had long ago ceased to make any effort to entertain her, and was mostly occupied in trying to maintain a facetious conversation with some friends in the rear. Ada and her escort were standing arm-in-arm, their heads very close together, completely engrossed in their two selves.

The long wait came to an end at last. On the part of the two men there was a rush for the front seats the moment the portals were passed. The girls followed in more sober fashion. Ada looked at her companion with concern.

"You're awful pale, Eleanor. Ain't you feeling well?"

"It was rather a long wait," Eleanor answered. "I shall be better directly we sit down."

They joined the two men, flushed with success, and eager for congratulations. There had been a few words with an old gentleman in front of whom they had slipped, and there were some loud complaints from a stout elderly lady and her two daughters, who for the next half-an-hour made audible remarks to one another as to the undesirable people with whom one was forced to rub shoulders in these democratic times. But on the whole they won their place of vantage cheaply, and settled down to make the most of it. Even Eleanor, to whom the warmth and the rest were inexpressibly grateful, found herself interested in the programme which Mr. Chadwick placed gallantly in her hand.

"It's the usual sort of play, you know," he remarked, in a superior tone. "A woman too many—and all the rest of it. Very smartly done, though. I shall have to make a few notes. I'm not sure whether our people have noticed it yet, but they'll be sure to want to know my opinion."

Eleanor eyed him critically. Less than ever in the gaslight did he repay inspection. His shirt was distinctly soiled, his hands and nails were unwashed, his eyes were puffy and weak. What a cavalier! She shuddered as she looked away again into the stalls.

"Like to know who some of the people are?" he inquired. "That's the Earl of G., just come in with Lady C., his sister, you know. The Rothschilds are in that box, and the Arthur Pagets in the other. See that little chap! It's Hertz, the South African millionaire."

"Don't point!" she exclaimed involuntarily. He looked annoyed.

"I'll look after that, thanks," he remarked. "I should say I'm more used to these sort of places than you are. My eye, there's the Duchess of K. Ain't her diamonds a treat?"

"Your acquaintance with the aristocracy," she remarked, "seems to be most extensive!"

"And a good many of 'em know me," he asserted. "You see, if you've anything to do with a Society paper you're right inside the ropes. All sorts of people pal me up now and again."

She made no remark, but unfortunately for her comfort Mr. Chadwick at that moment made a surprising discovery. This friend of Ada's, whom outside he had set down as a pale-faced nonentity without looks or conversation, was a very different sort of person in the gaslight. Now that the color had come back to her cheeks she was amazingly good-looking; capital style too, Mr. Chadwick decided—and Mr. Chadwick was a judge. He communicated his discovery to Henry in a somewhat audible whiz per, and Henry passed it on with a nudge to Ada.

"Chadwick's a clean goner!" he informed her. "Clean bowled over. Nice thing for her, ain't it?"

Ada was doubtful. She knew the meaning of those scornful, tremulous lips, and Eleanor's cold monosyllables were not encouraging. But Mr. Chadwick was not the man to be easily daunted.

"Bit annoyed with me, my boy, because I didn't cotton to her outside," he whispered to Henry. "You leave her to me. She'll come round. I know her sort—high fliers; but bless me, girls are all the same."

Fortunately for the preservation of his self-confidence the curtain went up. After that his whispered asides failed even to annoy her. She passed easily and with delightful readiness into another world, and in it there was no place for Mr. Chadwick.

It was an ordinary pleasant little comedy of everyday life, brightly written and epigrammatic, leading up, however, to a great situation towards the climax of the third act. Eleanor sat quite still, her eyes bright, her cheeks flushed, drinking in long draughts of delicious enjoyment. It was a chapter from the life for which her heart was faint with longing. Here was everyday existence without labor or vulgarity. She was too absorbed to torture herself with contrasts. With an abandon which was in itself a luxury, she gave herself wholly up to the delight of the moment.

During the intervals the glamour lasted and sustained her. She chatted brightly to her companions, and to spare herself the pain of any jarring note virtually absorbed the conversation. Ada beamed all over with pleasure. She was delighted that her friend should vindicate the superiority which she had bespoken for her. The two young men were amazed. Henry, with the unerring instinct of a born shopwalker, and Mr. Chadwick, who despite his innate vulgarity was gifted with perceptions, recognized that touch of something outside their lives with which Eleanor was certainly endowed. The former became curiously silent, the latter lost a great part of his offensive overconfidence. The first two intervals passed almost gayly.

Then the supreme moment of the play arrived. The woman of fashion who had chattered her way lightly through a couple of acts found herself face to face with one of the great realities of life. Her well-bred indifference fell away from her like a mask. She stood upon the stage, a white-faced, trembling human being, looking with wide-open eyes which took no account of visible things into a future which the next few seconds must decide for her.

Slowly her lips moved; the words came out faltering, but distinct, quivering with agony, like live things beating upon the air. She spoke her own sentence—accepted a renunciation magnificent, but impossible. She sank into a chair. Eleanor, withdrawing her eyes, hot and throbbing with unshed tears, found them challenged and held. A man from amongst the shadows of a private box was watching her intently.

She recognized him at once. He was leaning up against the wall, looking at her over the heads of the two women who occupied the front seats of the box. His posture and general air was of indifference, as though the play had failed to interest him. Yet when he saw her his expression changed, and as their eyes met he smiled quietly. Eleanor felt her breath die suddenly away from her. She would even have avoided his gaze, but she was powerless. His recognition was courteous enough, even kindly. Yet she felt that beneath it lay a perfect apprehension of her position, of the misery through which she had passed. The telegraphy of thought seemed to her then a very real and actual thing! His lips never moved, his face after that brief smile was almost statuesque. Yet his sympathy made her heart leap, she was conscious of an emotion wholly new, altogether un-analyzed. Every word of their conversation was in her mind. For the first time she realized that under-note of confidence in all that he had said to her which had alarmed even Ada. His words were true. She was the woman for whom he had been seeking. To him would belong her future. From that moment she was sure of it. Then from the stage rang out the long-drawn, passionate cry of a woman:

"What does it matter though my measure of days be long or short, only let me live through them, not grope my way as one of a herd. Ay, live, whether it be in sin or in well-being, in joy or in misery. Life is the one priceless gift, free, vigorous, pulsating. Break down the walls! Give me a year, a month, a week, and when it has passed I will take death by the hand. Yet, O God, how hard to shake the prison bars."

The passionate, almost shameless cry of the woman seemed still to echo through the house after the curtain had fallen. Eleanor sat quite still, her heart beating fiercely, her whole being in quivering accord with the words which might almost have sprung from her own lips. Against her will she looked once more into the box. He had withdrawn his gaze, and was talking now to the two women between whom he sat. She watched him steadfastly, eager to form a dispassionate and studied opinion of the man who had come so curiously into her life. For the first time she realized that he was more than ordinarily good-looking. His complexion was very pale, but it was a pallor without any suggestion of ill-health. His features were all good; his eyes clear and bright, although a trifle sunken beneath a formidable forehead; his hair, carefully parted, was dark and glossy. The lines of his mouth were firm, but not forbidding, the general strength of his face was almost impressive. In his quiet evening dress he seemed to her to possess more than ever that non-assertive, well-groomed appearance which is the corollary of distinction. She concluded her study of him and touched her escort upon the arm.

"You know every one, Mr. Chadwick. Can you tell me who those people are in the box to the left?"

"Which one do you mean?" he asked eagerly. "The one next the Pagets?"

She inclined her head cautiously, and his eyes followed her motion.

"Oh, him! That's Sir Powers Fiske. He's quite a big pot."

"Who is he?" Eleanor asked.

"I know a bit about him," Mr. Chadwick affirmed with complacency. "He started life as a doctor, came in for the baronetcy and a pile of money, chucked everything and went abroad for five years. He got lost in Central Asia, and when he came back he lectured before a lot of societies, and he's got half the letters in the alphabet after his name. I don't know what he does now just enjoys himself, I suppose."

"And the ladies?" Eleanor asked. "Is he married?"

"Don't think so. The old geez—lady with the diamonds is his mother, Lady Fiske. The other's his sister, I suppose. She looks like him."

The curtain rose again. A superfluous fourth act did its best to weaken the general effect of the play. With its fall there was a rush for the door. Eleanor gave one backward glance, but Sir Powers Fiske was helping his womenkind with their opera cloaks. Then again there was a hateful scrimmage, but outside the conditions had improved. The sky was clear of clouds, the stars were shining, and a fresh breeze seemed to Eleanor a delicious change after the stuffy atmosphere of the theatre. They turned up the Haymarket, and as they passed from under the portico, Eleanor was amazed to hear a whisper in her ear:

"I shall write to you to-morrow!"

She walked on, making no sign. Directly afterwards a brougham drawn by a pair of powerful horses passed them close to the curb-stone. A man was sitting on the back seat, and for a moment the gaslight fell upon his still, cold face. He looked steadily at the little party, but without any sign of recognition. The carriage swept round a corner. Ada leaned forward.

"Did you see who that was, Eleanor?" she asked eagerly.

"Yes, I saw him in the theatre," Eleanor answered.

Ada tossed her head.

"Looked as though he's never seen us before in his life," she whispered. "If we were good enough to take out to tea we ought to be good enough to acknowledge in the streets. I don't call it gentlemanly of him at all."

Eleanor made no remark. A certain restraint seemed to have fallen upon their two cavaliers. They walked all four together, Mr. Johnson having resisted an attempt on the part of his friend to detach Eleanor and walk behind. Ada was on the inside and Eleanor between the two. The attention of both seemed fixed upon her.

"I hope that you've enjoyed the play, Miss Surtoes?" Mr. Johnson asked anxiously.

Eleanor withdrew her eyes from the corner round which the carriage had vanished.

"Immensely, thank you," she answered warmly. "Really, it has been a great treat for me. It is very kind of you and Ada to have brought me."

Mr. Chadwick coughed.

"It was lucky," he remarked, "that I was able to get seats. The play is thought a lot of, and there are very few orders being given."

"It was very nice of you to include me in your invitation," Eleanor said absently. "What a sight this is!"

They were at the top of the Haymarket. All around them streams of people were pouring out from the theatres and the music halls. Cabs and carriages full of men and women in evening dress blocked all the thoroughfares. A glare of lights from the restaurants and the Leicester Square music halls turned night into day. The pavements were crowded with wayfarers of all sorts and conditions. It was the nightly pandemonium of the West End, when class jostles class, when the great streams of pleasure-seekers seize upon a few acres of their great city, and seek for relaxation with something of that same feverish absorption with which throughout the day they fight their battle in the greater struggle for existence. To Eleanor, who had seen little enough of it, there was a curious fascination in this brilliant and light-hearted mammon show. Even the dark places were tinselled over. It was early yet for the dregs.

"Cheerful sight, ain't it?" Mr. Chadwick remarked. "You're not a Londoner, perhaps, Miss Surtoes?"

She shook her head.

"No! I have lived nearly all my life in the north of England, Is it like this every night?"

"There's never any change to speak of. No place like it in the world, you know."

Mr. Chadwick, who had never been out of England save once for a day trip to Boulogne, spoke with the bland and insular confidence of his class. All the while he had been feeling surreptitiously in his trousers pocket. What he found was apparently satisfactory.

"Henry, my boy," he said suddenly, "what about a bit of supper, eh? That is, if Miss Surtoes will favor us?" he added, turning towards her deferentially.

"It is my treat," Mr. Johnson declared, with some asperity. "I was on the point of proposing it. We will go to Gatti's—unless Miss Surtoes would prefer somewhere else."

Eleanor glanced across to Ada, who had been walking almost by herself. Neither of the two men had addressed a word to her since leaving the theatre.

"What do you say, Ada?" she asked. "Have we time?"

"There is plenty of time, but Gatti's is a little expensive," Ada answered guardedly. "I don't think that I am very hungry."

"The expense has nothing to do with it," Mr. Johnson declared, somewhat nettled. "Supper we will have, that's certain. I always think it's the proper way to end an evening like this. The only question is, where we shall go to."

Mr. Chadwick had an inspiration.

"What price Frascati's!" he exclaimed. "There's music there, and it's close to Bearmain's. Are you fond of music, Miss Surtoes?"

"I like music very much," she answered, "but I think, perhaps, that Ada is right. We have had a very pleasant evening, and I am sure supper is quite unnecessary."

The two young men waived aside her remonstrance. Ada, in response to a vigorous nudge from Mr. Johnson, admitted to an appetite. They set out for Frascati's.

The big restaurant was crowded, but Mr. Chadwick, who seemed to have friends everywhere, prevailed upon a waiter whom he called by his Christian name, and patronized in a lordly way, to show them to a table at the far end of the room. Eleanor, to whom had come a brief spell of wonderful lightheartedness, was the life and soul of the little party. The cosmopolitanism of the place, the warmth, the music, and the cheerful hum of conversation, all had an effect upon her. The event of the afternoon, those few words which seemed still to linger in her ears, had touched her imagination. After all, she was very young. These people were doing their best to be kind to her. To let herself go on a momentary wave of enjoyment seemed to her after all a natural thing. With her sudden access of spirits the change in her appearance was wonderful. A faint flush of color brought out the delicate faultlessness of her complexion, her eyes were brilliant, the feverish mirth seemed to send the words dancing from her lips. She took no note of Ada's silence, or of the fact that both young men vied with one another in their attentions to her. She accepted the champagne which Mr. Chadwick had ordered with the air of a prince, wholly unmindful of Ada's barely repressed disapproval. The delight of even these few minutes' respite from the drudgery of a hated life, of feeling the blood once more warm in her veins, was like a spell upon her. After all, it was short-lived enough! When they rose to leave the restaurant and were making their way towards the door, she felt a little touch upon her arm. Mr. Johnson was by her side. "I say, let's all walk home together," he whispered hurriedly. "Don't go off with Chadwick, will you?"

She was on the point of assenting to a proposition which she herself would have much preferred, when something in his face aroused her to some confused sense of the position. She looked at him in chilling surprise.

"I think it is quite time," she said, "that you made yourself agreeable to Ada. Of course she is expecting you to walk home with her. I shall wait behind for Mr. Chadwick."

"I'm not engaged to her—not properly," he said, in a low, eager tone.

Ada was just in front. Her somewhat dumpy little figure was at its worst in an ill-fitting jacket. She walked with a somewhat mincing and conscious gait, affecting to be busy with her gloves. Between her and the girl at his side, whose natural elegance triumphed over shabby clothes, there could be no manner of comparison. He looked up at her pleadingly. She ignored him altogether. At the door she touched Ada on the shoulder.

"Ada," she said, "will you and Mr. Johnson walk on. I will wait for Mr. Chadwick. He has lost his stick or something."

Henry's look of reproach was wasted upon her. He and Ada moved off together. Mr. Chadwick came out beaming, a big cigar in his mouth and his ill-brushed silk hat set on the back of his head.

"Good business," he exclaimed cheerfully. "I knew Henry's game, so I hung round a bit inside—couldn't find my hat, you know. Two's company—four ain't. What do you think, Miss Surtoes?"

The momentary light-heartedness had passed away. She looked at him in cold disapproval, from her standard of taste a wholly impossible being, vulgar, devoid of all niceness of person, offensively familiar.

"I have no preference," she answered coldly. "Only as Ada is engaged to Mr. Johnson it seemed to me that they might like to be together. There really isn't the least need for you to come out of your way, Mr. Chadwick. I know my way home, and I can keep them in sight."

Mr. Chadwick looked at her in amazement.

"Oh, come on!" he exclaimed facetiously. "That's a bit thick, isn't it? As if you didn't know I've been looking forward all supper-time to this walk with you."

She was silent. Mr. Chadwick, who was not used to under-estimate himself and his powers of attraction, decided that the change in her manner was one of those feminine wiles designed to enslave him the more deeply. It was by no means her intention to be taken seriously.

"Don't let's hurry," he said. "It's a beautiful night, and you've got till twelve o'clock. Not over-strict at Bearmain's, are they? That sort of thing don't do nowadays."

They met with a stress of traffic. He attempted to draw her arm through his and was promptly repulsed.

"Please do not attempt anything of that sort again," she exclaimed indignantly. "It is most offensive to me."

Mr. Chadwick stared at her. It was obvious that she was in earnest. She quickened her pace, and he walked by her side in silence. After all, she was scarcely like Ada and the rest. Perhaps his gallantry had been a little premature. Presently he attempted a clumsy apology.

"Sorry I tried to take your arm," he said. "I'd no idea you'd have any objection. I forgot we weren't very well acquainted."

"It is of no consequence," Eleanor answered coldly.

"Haven't offended you in any other way, have I?" he asked. "You seem mighty quiet."

"On the contrary, you have given me a very pleasant evening, for which I thank you," she said. He coughed. His experience of young women of such aloofness was limited. He began to feel aggrieved. The theatre tickets had been his, and he had paid for the champagne—a prodigality which would seriously affect his meals during the coming week. He was not getting value for his money.

"What about next Thursday?" he asked. "Will you come for a bit of a walk with me?"

"No, thank you," she answered decidedly.

"Why not?" he persisted.

"Because I do not care about that sort of thing at all!" she said.

He threw away his cigar viciously.

"You'd go to the theatre fast enough, I suppose!" he remarked.

She looked at him with some surprise. His ill-humor was incomprehensible to her.

"I should not go with you," she said calmly.

An ugly expression narrowed his eyes.

"Didn't know I was coming to-night, I suppose?" he remarked.

"I did not," she answered. "Ada asked me to go with Mr. Johnson and herself."

"You are quite sure there's no mistake?" he asked, with clumsy sarcasm. "You are one of Bearmain's girls, and not a duchess in disguise."

She vouchsafed him no answer, but turning on her heel crossed the street. He followed, but had hard work to keep up with her.

"I ain't going to be shaken off," he said doggedly. "I can walk as fast as you any day."

She made no remark. He watched her for a moment. The lithesomeness of her walk fascinated him. She possessed the grace of rapid and effortless movement.

"Look here," he said, "I don't know what I've said or done to offend you, but I apologize. I can't say anything fairer than that, can I? I apologize. You understand! Don't go away like this. I tell you I haven't seen any one for years who's taken my fancy so much as you have, and it's stupid to quarrel before we know one another."

"I don't want to know you," she answered wearily. "I am very much obliged for your kindness this evening, but I wish you'd go away now."

He gave vent to an exclamation which closely resembled a snort.

"Well, that's a nice way to talk," he said sullenly. "I shan't bite, anyhow! I suppose there's some one else, eh? Just my luck!"

She made no reply, but still further quickened her pace. Mr. Chadwick remembered that in the textbook of his gallantry was an axiom that women of spirit liked to be treated with spirit. He decided upon bolder measures. He leaned suddenly towards her, and his hand rested for a moment upon her waist. She sprang away with marvellous swiftness, and struck the face which had very nearly touched hers with ungloved hand. Mr. Chadwick, who was altogether unprepared for such a vigorous defence, staggered back with a cry of pain. Eleanor caught up her skirts, and ran with a speed which rendered pursuit hopeless up the dark street. She was on the doorstep of Bearmain's in a moment or two. Ada and Henry were still standing there.

"What is it?" Ada cried.

Eleanor leaned against the wall, panting.

"That beast of a man!" she exclaimed. "Oh, let us get in quickly."

Henry, without a word of good-night, left them. Ada watched him anxiously, but Eleanor was unconscious of his going. The door opened, and she pushed her way inside, ran up the narrow stairs, and into her room. Then she stood quite still, and drew a long sigh of relief.

Slowly she drew off her hat and jacket, and replaced her wet boots with slippers. Then, though the night was cold, she threw open the window and leaned out. Below in the street two men were quarrelling, the hum of traffic still rolled along the Edgware Road. But she took no heed of these things. Her eyes were fixed upon the sky, lurid still with the fire of the awakened city. She drew in long breaths of the pure, crisp air. Here was peace for a little time—and afterwards. What manner of death could this be of which he had warned her?

Taws followed for Eleanor a succession of dreary days, differing only from those which had gone before in the somewhat altered demeanor of those around her. Johnson, on whose left cheek was a patch of sticking-plaster where Chadwick's fist had cut through to the bone, seemed to find endless excuses for hovering around her end of the counter. He offered her many small services, few of which she accepted, and was always nervously anxious that no undue share of work should fall to her lot. A few yards away from her Ada stood, pale and heavy-eyed, neglected all the day by her former admirer, who scarcely vouchsafed her a glance. The girls made unkind remarks in Eleanor's hearing. Popular sympathy was with Ada, and it was openly expressed.

Johnson, although he made many attempts, found A hard to see anything of Eleanor alone. One afternoon, however, they came face to face in the passage leading to the tea-room. Instead of avoiding him, she waited. He came hurrying up to her.

"Mr. Johnson," she said, "you are treating Ada very badly."

"Miss Smart is nothing to me," he answered. "I told you before that we were not engaged."

"You were friends, at any rate," she answered. "You spent your Thursday evenings together. You took her out continually. Now without a 'word of explanation you simply ignore her."

"I cannot help it," he answered simply. "It is your fault."

"My fault!" she repeated indignantly. "What do you mean?"

"I cannot think of her because I cannot think of anybody else but you," he answered. "I know it's presumption. You're different. You're a lady. It's easy to see that. I can't help it, Miss Surtoes; please don't be angry with me. My people are quite well off, and I am only here to learn the business. Will you come out with me to-morrow evening?"

She looked at him with flashing eyes.

"How dare you ask me such a thing," she exclaimed indignantly. "Ada is my friend—the only girl here who has been decent to me. If you say another word of that sort to me I'll never speak to you again."

He looked at her, pale with anxiety.

"I can't help it about Ada," he said. "As long as I live I couldn't care for her now. It's you or nobody, Miss Surtoes."

"Then it will certainly be nobody," Eleanor answered haughtily. "You must be out of your senses."

She swept past him into the tea-room. Ada came and sat by her side.

"You were talking to Henry," she remarked. "Did he say anything about me?"

"He said some very foolish things, dear," Eleanor answered kindly. "Men are like that sometimes, you know, Ada, especially at his age. It will all come right, I am sure."

Ada mopped her eyes.

"I can't tell what's come over him, I'm sure," she said ruefully. "He used to be so sensible. It isn't like him a bit to hang round any one as he does you, and you scarcely civil to him. He must be very fond of you, Eleanor. I've seen him stand and watch you—well, he never looked at me like it."

Eleanor laughed.

"If I were you, Ada," she said, "I should not let him see that it troubled me. If he doesn't ask you to go out to-morrow, couldn't you find some one else to take you just for one evening?"

Ada shook her head pitifully.

"I couldn't do it," she said. "I couldn't go out with any one but Henry. May I ask you something, Eleanor?"

"Of course!"

"Has he asked you to go out with him tomorrow?"

"He said something about it," Eleanor admitted. "Of course, I shouldn't think of going. You know that."

Ada flushed a little.

"The beast! And only last week he declared that there would never be any one else but me that he'd care to take out. Eleanor, I wonder why men are so much more changeable than women?"

"I wonder!"

There was a short silence. Ada was studying her friend's face.

"Eleanor, may I ask you something?"

Eleanor nodded.

"Yes."

"Were you ever engaged?"

Eleanor was silent. A curious hardness had stolen into her face. Yet when she spoke her tone was matter-of-fact enough.

"Yes, I was engaged before I came here," she admitted.

"And were you very fond of him?"

"I suppose so—in a way," Eleanor answered. "I don't think that I was very much in love. I was too young. But I felt it terribly when it was broken off. I think that it was my vanity which suffered most."

"Wasn't it your fault, then, that it was broken off?"

"No! It came with the rest of my troubles. I don't think I care to talk about it any more, if you don't mind."

The bell rang, and they hastened back to work. On the way some one handed Eleanor a letter. She glanced at the address, and put it calmly in her pocket. Ada, who was by her side, noticed the thick square envelope and crest.

It was several hours later before she gained the shelter of her room, and had an opportunity of opening it. The contents were brief enough, but to the point:

"131 HANS CRESCENT PLACE, LONDON.

"DEAR Miss Surtoes,—I think you said that you were generally disengaged on Thursday evenings. I should be very glad if you would dine with me tomorrow evening quietly somewhere, and go to a theatre afterwards. I would either call for you, or, if you prefer it, meet you at the corner of Oxford Street and Bond Street. If I hear nothing from you I shall be there at seven o'clock.—Yours sincerely,

POWERS FISKE."

She replaced the letter in the envelope, and sat down by the open window. The luxury of a room to herself was only a temporary one. In a week or two at the outside the other little iron bedsteads would be occupied, and these few moments of freedom would be denied her. She told herself that she would make up her mind whether or no to accept this invitation. All the while she knew that she was trifling with herself. Her decision was already arrived at. Only there was so much that was strange in her meeting with this man, so much that was mysterious in his calmly avowed intentions towards her. Ada's earnest warnings she took little account of. She trusted him entirely.

Presently she dragged out from its hiding-place and unlocked a box which she had not opened since her arrival at Bearmain's. She looked it over thoughtfully. The things were a little old-fashioned, but of a different order altogether to anything which she had worn recently. She selected a dress, and fell asleep re-trimming a hat.

All the next day she was conscious that Ada was watching her with nervous anxiety. The hours seemed to drag along, the day was surely the longest she had ever known. At last it was over. She hurried to her room, slipped off her dress, and with beating heart began her transformation. When she had finished, and she surveyed herself in the small cracked mirror, she drew a little sigh of relief. It was the old Eleanor who was smiling at her. Of the shop-girl there was no single trace left.

Just as she was ready Ada knocked timidly at the door. She gave one glance at Eleanor, and sinking down upon the bed, burst into tears.

"My dear child!" Eleanor exclaimed, "whatever is the matter?"

"You are going to him!" Ada sobbed. "I knew it!"

Eleanor laughed a little scornfully.

"I am going out to dinner with him, and perhaps to a theatre," she said. "Why on earth shouldn't I?"

"Because you are too good for any man to amuse himself with—especially that one," she answered. "You think I am a fool, I know, Eleanor, but I've been here seven years, and all the girls who have ever been out with gentlemen have—they haven't stayed here. It's begun by going out to dinner, and afterwards none of the young men about here were ever good enough for them. It's always the nicest girls, too, and the prettiest. Don't go, dear. You may have—Henry!—I—I don't care! But—don't go!"

Eleanor laughed softly.

"It's very nice of you to mind so much, dear," she said, sitting by her side for a moment, and taking her hand. "Now, listen. I am absolutely and perfectly safe, and I am not a silly child to be flattered into doing anything foolish. I want to understand what he meant the other afternoon—you know that I am very miserable here, and if there is any honest means of escape I want to know all about it."

"You're sure you won't take to going out with him regular?" Ada pleaded. "I know I'm foolish, but there was Lyddy Green—she was almost a lady, and such a dear—"

Eleanor broke away.

"I am late already," she said. "I mustn't stay another moment. Sit up for me if you like, and I'll tell you all about it when I come home."

She hurried away, and within a few feet of the front door came face to face with Mr. Johnson. He was carefully dressed, and smoking a cigarette, which he threw away directly she appeared. He took off his hat with shaking fingers. He was white and red almost at the same time. He could scarcely stand still for nervousness.

"Good evening, Miss Surtoes!"

She looked at him coldly.

"Good evening, Mr. Johnson. You must excuse my stopping, if you please. I am in a hurry."

"I thought perhaps," he faltered, "that you might come for just a short walk—or some dinner."

She stopped short.

"I have an engagement, Mr. Johnson," she said; "and in any case, I have told you distinctly that I do not desire your company."

"It's because of Ada! I know it is!" he pleaded. "I'll make it all right with her. Let me walk a little way with you."

"No!"

"Just to the corner of the street."

"If you do," she answered, "I shall never speak to you again."

He was suddenly pale. He saw a familiar figure lounging against a pillar-box at the corner of the street.

"You ain't going with Chadwick?" he exclaimed.

She shivered.

"Don't ask me such insulting questions."

Mr. Johnson was immensely relieved. He indicated the waiting figure.

"Well, he's hanging about," he exclaimed gloomily. "I suppose he knew this was our evening."

Eleanor stopped short. Mr. Chadwick was watching them with some hesitation. He wore a large flower in his button-hole, and a black shade over his left eye.

"Mr. Johnson," she said, "could I trouble you to call a hansom for me?"

He sighed.

"It's a pleasure to do anything for you, Miss Surtoes," he said. "You really have an engagement, then?"

"I really have."

Mr. Johnson called a hansom, and handed her in. She leaned over the apron.

"Mr. Johnson," she said, "will you do something to please me?"

"Anything!" he exclaimed vigorously.

"Go back and ask Miss Smart to go for a walk. She has a headache, I know, and it will do her good."

He stifled a sigh.

"If you wish it, Miss Surtoes. But I want you to understand there's nothing serious between Miss Smart and myself. We're friends, no more."

Chadwick walked by, and executed a profound salute. Eleanor looked coolly through him. It was a pleasurable moment for Mr. Johnson. The cab was on the point of starting.

She moved her head towards Mr. Chadwick's black shade.

"Mr. Johnson," she said, "did you do that?"

He looked sheepish for a moment, but her eyes compelled answer.

"Yes, Miss Surtoes."

She flashed a brilliant smile upon him and waved her hand.

"Thank you!" she called out.

"Yes," he said, smiling across the table at her, "you may ask me any questions you like. But you must remember that I do not promise to answer them."

"Nevertheless," she said thoughtfully, "I have come to-night for information. I must ask you to explain, if only vaguely, your words to me. I must have some sort of an idea as to what is in your mind."

"If you insist," he declared, "I can only answer you in this manner. The service which I may require of you is one which involves a certain risk to your life and health. That risk is very small, but it exists. You will suffer neither pain nor discomfort. You will be removed into another sphere altogether, and it is possible that you may take with you a somewhat cloudy recollection of this portion of your life. Your reward will be an established position in the world and an honorable one. Beyond this I cannot say a single word. In fact, you must consider the whole thing as only a possibility. I do not make you any offer for the present. I simply ask you to accept my acquaintance and give me some portion of your time."

Eleanor leaned back in her chair and slowly stirred her coffee. They were sitting at a small table in a quiet but fashionable London restaurant. A Viennese band was playing soft music, the room was full of smart and interesting people. Their dinner had been small, but perfect, a great handful of long-stemmed roses had just been presented to her by an obliging head-waiter. Her companion had been most entertaining. For the first time for years she had enjoyed the luxury of conversation with a person of culture and sympathies. A certain coldness which she had noticed in him upon their first meeting had gradually worn away, and he had at times shown signs of a geniality and sense of humor which came as a surprise to her. From whatever point of view she regarded it, their meeting had been a success. She was ready enough, for the moment, to waive all further explanations.

"There is only one thing I should like to add, Miss Surtoes," he said, glancing at the clock. "It would be a great pleasure to me to have you meet my mother and sister, and under ordinary circumstances I should not ask you for your friendship until I had done so. But as it happens, nothing of this sort can happen for the moment, because if we should ever carry out the scheme which I have in my mind, you will be associated with them in somewhat different fashion. This sounds terribly complicated, doesn't it?" he added. "I'm afraid I have not the gift of concise expression."

She laughed.

"You are a very mysterious person altogether," she said. "As for meeting your mother and sister, it is very good of you to suggest it, but of course it would not be possible in my present position. There is one thing more which I am going to ask you, anyhow. What extraordinary chance made you select me as your—what shall I say, victim?"

"I strongly object to the term," he answered, smiling, "and the question itself is not a very easy one to answer. In fact, I cannot answer it. Do you see that it is nine o'clock, and I have seats for Wyndham's? Shall we go?"

She rose at once, and they left the room together. Outside he would have called a hansom, but she checked him.

"It is only five minutes away," she said, "and the air is so delicious. Do you mind walking?"

He too preferred it. They strolled through the crowded streets almost in silence. Eleanor was too preoccupied for conversation. Powers seemed absorbed by his cigarette. But as they neared the theatre she turned towards him.

"It appears to me," she said, "that I am entering upon a sort of probationary period. At least, may I not have an idea its to how long it must last?"

"It need not be very long," he said thoughtfully-. "There are two things which I must ask from you: first, your entire trust; secondly, that you tell me the whole of the important features of your past history."

"The first," she said, "I think you already have. The second—is that really necessary?"

"Absolutely."

"I will tell you all that you need know whenever you choose to ask," she said.