RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

"A Maker Of History," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1906

"Those who read A Maker of History will revel in the plot, and will enjoy all those numerous deft touches of actuality that have gone to make the story genuinely interesting and exciting." --The Standard.

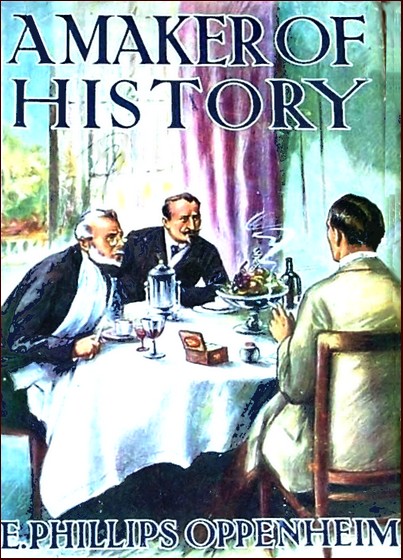

"A Maker Of History," Hodder & Stoughton reprint, 1919

"A Maker Of History," Hodder & Stoughton reprint, ca. 1930

Frontispiece

He came and stood a few feet away from them.

The boy sat up and rubbed his eyes. He was stiff, footsore, and a little chilly. There was no man-servant arranging his bath and clothes, no pleasant smell of coffee—none of the small luxuries to which he was accustomed. On the contrary, he had slept all night upon a bed of bracken, with no other covering than the stiff pine needles from the tall black trees, whose rustling music had lulled him to sleep.

He sat up, and remembered suddenly where he was and how he had come there. He yawned, and was on the point of struggling to his feet when he became aware of certain changed conditions in his surroundings. Some instinct, of simple curiosity perhaps, but of far-reaching effect, led him to crawl back into his hiding-place and watch.

Last night, after many hours of painful walking, two things alone had impressed themselves upon his consciousness: the dark illimitable forest and the double line of rails, which with the absolute straightness of exact science had stretched behind and in front till the tree-tops in the far distance seemed to touch, and the rails themselves to vanish into the black heart of the close-growing pines. For miles he had limped along the painfully rough track without seeing the slightest sign of any break in the woods, or any human being. At last the desire for sleep had overtaken him. He was a hardy young Englishman, and a night out of doors in the middle of June under these odorous pines presented itself merely as a not disagreeable adventure. Five minutes after the idea had occurred to him he was asleep.

And now in the gray morning he looked out upon a different scene. Scarcely a dozen yards from him stood a single travelling-coach of dark green, drawn by a heavy engine. At intervals of scarcely twenty paces up and down the line, as far as he could see, soldiers were stationed like sentries. They were looking sharply about in all directions, and he could even hear the footsteps of others crashing through the wood. From the train three or four men in long cloaks had already descended. They were standing in the track talking together.

The young man behind the bracken felt himself in somewhat of a dilemma. There was a delightful smell of fresh coffee from the waiting coach, and there seemed to be not the slightest reason why he should not emerge from his hiding-place and claim the hospitality of these people. He was a quite harmless person, with proper credentials, and an adequate explanation of his presence there. On the other hand, the spirit of adventure natural to his years strongly prompted him to remain where he was and watch. He felt certain that something was going to happen. Besides, those soldiers had exactly the air of looking for somebody to shoot!

Whilst he was hesitating, something did happen. There was a shrill whistle, a puff of white smoke in the distance, and another train approached from the opposite direction.

It drew up within a few feet of the one which was already waiting. Almost immediately half a dozen men, who were already standing upon the platform of the car, descended. One of these approached rapidly, and saluted the central figure of those who had been talking together in the track. After a few moments' conversation these two, followed by one other man only who was carrying a writing portfolio, ascended the platform of the train which had arrived first and disappeared inside.

The young man who was watching these proceedings yawned.

"No duel, then!" he muttered to himself. "I've half a mind to go out." Then he caught sight of a particularly fierce-looking soldier with his finger already upon the trigger of his gun, and he decided to remain where he was.

In about half an hour the two men reappeared on the platform of the car. Simultaneously the window of the carriage in which they had been sitting was opened, and the third man was visible, standing before a small table and arranging some papers. Suddenly he was called from outside. He thrust his hat upon the papers, and hastened to obey the summons.

A little gust of breeze from the opening and closing of the door detached one of the sheets of paper from the restraining weight of the hat. It fluttered out of the window and lay for a moment upon the side of the track. No one noticed it, and in a second or two it fluttered underneath the clump of bracken behind which the young Englishman was hiding. He thrust out his hand and calmly secured it.

In less than five minutes the place was deserted. Amidst many hasty farewells, wholly unintelligible to the watcher, the two groups of men separated and climbed into their respective trains. As soon as every one was out of sight the Englishman rose with a little grunt of satisfaction and stretched himself.

He glanced first at the sheet of paper, and finding it written in German thrust it into his pocket. Then he commenced an anxious search for smoking materials, and eventually produced a pipe, a crumpled packet of tobacco, and two matches.

"Thank Heaven!" he exclaimed, lighting up. "And now for a tramp."

He plodded steadily along the track for an hour or more. All the time he was in the heart of the forest. Pheasants and rabbits and squirrels continually crossed in front of him. Once a train passed, and an excited guard shouted threats and warnings, to which he replied in fluent but ineffective English.

"Johnnies seem to think I'm trespassing!" he remarked to himself in an aggrieved tone. "I can't help being on their beastly line!"

Tall, smooth-faced, and fair, he walked with the long step and lightsome grace of the athletic young Englishman of his day. He was well dressed in tweed clothes, cut by a good tailor, a little creased by his night out of doors, but otherwise immaculate. He hummed a popular air to himself, and held his head high. If only he were not so hungry.

Then he came to a station. It was little more than a few rows of planks, with a chalet at one end—but a very welcome sight confronted him. A little pile of luggage, with his initials, G. P., was on the end of the platform nearest to him.

"That conductor was a sensible chap," he exclaimed. "Glad I tipped him. Hullo!"

The station-master, in uniform, came hurrying out. The young Englishman took off his hat, and produced a phrase book from his pocket. He ignored the stream of words which the station-master, with many gesticulations, was already pouring out.

"My luggage," he said firmly, laying one hand upon the pile, and waving the phrase book.

The station-master acquiesced heartily. He waxed eloquent again, but the Englishman was busy with the phrase book.

"Hungry! Hotel?" he attempted.

The station-master pointed to where the smoke was curling upwards from a score or so of houses about half a mile distant. The Englishman was getting pleased with himself. Outside was a weird-looking carriage, and on the box seat, fast asleep, was a very fat man in a shiny hat, ornamented by a bunch of feathers. He pointed to the luggage, then to the cab, and finally to the village.

"Luggage, hotel, carriage!" he suggested.

The station-master beamed all over. With a shout, which must have reached the village, he awakened the sleeping man. In less than five minutes the Englishman and his luggage were stored away in the carriage. His ticket had been examined by the station-master, and smilingly accepted. There were more bows and salutes, and the carriage drove off. Mr. Guy Poynton leaned back amongst the mouldy leather upholstery, and smiled complacently.

"Easiest thing in the world to get on in a foreign country with a phrase book and your wits," he remarked to himself. "Jove, I am hungry!"

He drove into a village of half a dozen houses or so, which reminded him of the pictured abodes of Noah and his brethren. An astonished innkeeper, whose morning attire apparently consisted of trousers, shirt, and spectacles, ushered him into a bare room with a trestle table. Guy produced his phrase book.

"Hungry!" he said vociferously. "Want to eat! Coffee!"

The man appeared to understand, but in case there should have been any mistake Guy followed him into the kitchen. The driver, who had lost no time, was already there, with a long glass of beer before him. Guy produced a mark, laid it on the table, touched himself, the innkeeper, and the driver, and pointed to the beer. The innkeeper understood, and the beer was good.

The driver, who had been of course ludicrously over-paid, settled down in his corner, and announced his intention of seeing through to the end this most extraordinary and Heaven-directed occurrence. The innkeeper and his wife busied themselves with the breakfast, and Guy made remarks every now and then from his phrase book, which were usually incomprehensible, except when they concerned a further supply of beer. With a brave acceptance of the courtesies of the country he had accepted a cigar from the driver, and was already contemplating the awful moment when he would have to light it. Just then an interruption came.

It was something very official, but whether military or of the police Guy could not tell. It strode into the room with clanking of spurs, and the driver and innkeeper alike stood up in respect. It saluted Guy. Guy took off his hat. Then there came words, but Guy was busy with his phrase book.

"I cannot a word of German speak!" he announced at last.

A deadlock ensued. The innkeeper and the driver rushed into the breach. Conversation became furious. Guy took advantage of the moment to slip the cigar into his pocket, and to light a cigarette. Finally, the officer swung himself round, and departed abruptly.

"Dolmetscher," the driver announced to him triumphantly.

"Dolmetscher," the innkeeper repeated.

Guy turned it up in his phrase book, and found that it meant interpreter. He devoted himself then to stimulating the preparations for breakfast.

The meal was ready at last. There were eggs and ham and veal, dark-colored bread, and coffee, sufficient for about a dozen people. The driver constituted himself host, and Guy, with a shout of laughter, sat down where he was, and ate. In the midst of the meal the officer reappeared, ushering in a small wizened-faced individual of unmistakably English appearance. Guy turned round in his chair, and the newcomer touched his forelock.

"Hullo!" Guy exclaimed. "You're English!"

"Yes, sir!" the man answered. "Came over to train polo ponies for the Prince of Haepsburg. Not in any trouble, I hope, sir?"

"Not I," Guy answered cheerily. "Don't mind my going on with my breakfast, do you? What's it all about? Who's the gentleman with the fireman's helmet on, and what's he worrying about?"

"He is an officer of the police, sir, on special service," the man answered. "You have been reported for trespassing on the State railway this morning."

"Trespassing be blowed!" Guy answered. "I've got my ticket for the frontier. We were blocked by signal about half a dozen miles off this place, and I got down to stretch my legs. I understood them to say that we could not go on for half an hour or so. They never tried to stop my getting down, and then off they went without any warning, and left me there."

"I will translate to the officer, sir," the man said.

"Right!" Guy declared. "Go ahead."

There was a brisk colloquy between the two. Then the little man began again.

"He says that your train passed here at midnight, and that you did not arrive until past six."

"Quite right!" Guy admitted. "I went to sleep. I didn't know how far it was to the station, and I was dead tired."

"The officer wishes to know whether many trains passed you in the night?"

"Can't say," Guy answered. "I sleep very soundly, and I never opened my eyes after the first few minutes."

"The officer wishes to know whether you saw anything unusual upon the line?" the little man asked.

"Nothing at all," Guy answered coolly. "Bit inquisitive, isn't he?"

The little man came closer to the table.

"He wishes to see your passport, sir," he announced.

Guy handed it to him, also a letter of credit and several other documents.

"He wants to know why you were going to the frontier, sir!"

"Sort of fancy to say that I'd been in Russia, that's all!" Guy answered. "You tell him I'm a perfectly harmless individual. Never been abroad before."

The officer listened, and took notes in his pocketbook of the passport and letter of credit. Then he departed with a formal salute, and they heard his horse's hoofs ring upon the road outside as he galloped away. The little man came close up to the table.

"You'll excuse me, sir," he said, "but you seem to have upset the officials very much by being upon the line last night. There have been some rumors going about—but perhaps you're best not to know that. May I give you a word of advice, sir?"

"Let me give you one," Guy declared. "Try this beer!"

"I thank you, sir," the man answered. "I will do so with pleasure. But if you are really an ordinary tourist, sir,—as I have no doubt you are,—let this man drive you to Streuen, and take the train for the Austrian frontier. You may save yourself a good deal of unpleasantness."

"I'll do it!" Guy declared. "Vienna was the next place I was going to, anyhow. You tell the fellow where to take me, will you?"

The man spoke rapidly to the driver.

"I think that you will be followed, sir," he added, turning to Guy, "but very likely they won't interfere with you. The railway last night for twenty miles back was held up for State purposes. We none of us know why, and it doesn't do to be too curious over here, but they have an idea that you are either a journalist or a spy."

"Civis Britannicus sum!" the boy answered, with a laugh.

"It doesn't quite mean what it used to, sir," the man answered quietly.

Exactly a week later, at five minutes after midnight, Guy Poynton, in evening dress, entered the Café Montmartre, in Paris. He made his way through the heterogeneous little crowd of men and women who were drinking at the bar, past the scarlet-coated orchestra, into the inner room, where the tables were laid for supper. Monsieur Albert, satisfied with the appearance of his new client, led him at once to a small table, submitted the wine card, and summoned a waiter. With some difficulty, as his French was very little better than his German, he ordered supper, and then lighting a cigarette, leaned back against the wall and looked around to see if he could discover any English or Americans.

The room was only moderately full, for the hour was a little early for this quarter of Paris. Nevertheless, he was quick to appreciate a certain spirit of Bohemianism which pleased him. Every one talked to his neighbor. An American from the further end of the room raised his glass and drank his health. A pretty fair-haired girl leaned over from her table and smiled at him.

"Monsieur like talk with me, eh?"

"English?" he asked.

"No. De Wien!"

He shook his head smilingly.

"We shouldn't get on," he declared. "Can't speak the language."

She raised her eyebrows with a protesting gesture, but he looked away and opened an illustrated paper by his side. He turned over the pages idly enough at first, but suddenly paused. He whistled softly to himself and stared at the two photographs which filled the sheet.

"By Jove!" he said softly to himself.

There was the rustling of skirts close to his table. An unmistakably English voice addressed him.

"Is it anything very interesting? Do show me!"

He looked up. Mademoiselle Flossie, pleased with his appearance, had paused on her way down the room.

"Come and sit down, and I'll show it you!" he said, rising. "You're English, aren't you?"

Mademoiselle Flossie waved a temporary adieu to her friends and accepted the invitation. He poured her out a glass of wine.

"Stay and have supper with me," he begged. "I must be off soon, but I'm tired of being alone. This is my last night, thank goodness."

"All right!" she answered gayly. "I must go back to my friends directly afterwards."

"Order what you like," he begged. "I can't make these chaps understand me."

She laughed, and called the waiter.

"And now show me what you were looking at in that paper," she insisted.

He pointed to the two photographs.

"I saw those two together only a week ago," he said. "Want to hear about it?"

She looked startled for a moment, and a little incredulous.

"Yes, go on!" she said.

He told her the story. She listened with an interest which surprised him. Once or twice when he looked up he fancied that the lady from Vienna was also doing her best to listen. When he had finished their supper had arrived.

"I think," she said, as she helped herself to hors d'œuvre, "that you were very fortunate to get away."

He laughed carelessly.

"The joke of it is," he said, "I've been followed all the way here. One fellow, who pretended he got in at Strasburg, was trying to talk to me all the time, but I saw him sneak in at Vienna, and I wasn't having any. I say, do you come here every evening?"

"Very often," she answered. "I dance at the Comique, and then we generally go to Maxim's to supper, and up here afterwards. I'll introduce you to my friends afterwards, if you like, and we'll all sit together. If you're very good I'll dance to you!"

"Delighted," he answered, "if they speak English. I'm sick of trying to make people understand my rotten French."

She nodded.

"They speak English all right. I wish that horrid Viennese girl wouldn't try to listen to every word we say."

He smiled.

"She wanted me to sit at her table," he remarked.

Mademoiselle Flossie looked at him warningly, and dropped her voice.

"Better be careful!" she whispered. "They say she's a spy!"

"On my track very likely," he declared with a grin.

She threw herself back in her seat and laughed.

"Conceited! Why should any one want to be on your track? Come and see me dance at the Comique to-morrow night."

"Can't," he declared. "My sister's coming over from England."

"Stupid!"

"Oh, I'll come one night," he declared. "Order some coffee, won't you—and what liqueurs?"

"I'll go and fetch my friends," she declared, rising. "We'll all have coffee together."

"Who are they?" he asked.

She pointed to a little group down the room—two men and a woman. The men were French, one middle-aged and one young, dark, immaculate, and with the slightly bored air affected by young Frenchmen of fashion; the woman was strikingly handsome and magnificently dressed. They were quite the most distinguished-looking people in the room.

"If you think they'll come," he remarked doubtfully. "Aren't we rather comfortable as we are?"

She made her way between the tables.

"Oh, they'll come," she declared. "They're pals!"

She floated down the room with a cigarette in her mouth, very graceful in her airy muslin skirts and large hat. Guy followed her admiringly with his eyes. The Viennese lady suddenly tore off a corner of her menu and scribbled something quickly. She passed it over to Guy.

"Read!" she said imperatively.

He nodded, and opened it.

"Prenez garde!" he said slowly. Then he looked at her and shook his head. She was making signs to him to destroy her message, and he at once did so.

"Don't understand!" he said. "Sorry!"

Mademoiselle Flossie was laughing and talking with her friends. Presently they rose, and came across the room with her. Guy stood up and bowed. The introductions were informal, but he felt his insular prejudices a little shattered by the delightful ease with which these two Frenchmen accepted the situation. Their breeding was as obvious as their bonhomie. The table was speedily rearranged to find places for them all.

"Your friends will take coffee with me, Mademoiselle," Guy said. "Do be hostess, please. My attempts at French will only amuse everybody."

The elder of the two Frenchmen, whom the waiter addressed as Monsieur le Baron, and every one else as Louis, held up his hand.

"With pleasure!" he declared, "later on. Just now it is too early. We will celebrate l'entente cordiale. Garçon, a magnum of Pommery, un neu frappé! I know you will forgive the liberty," he said, smiling at Guy. "This bottle is vowed. Flossie has smiled for the first time for three evenings."

She threw a paper fan at him, and sat down again by Guy.

"Do tell him the story you told me," she whispered in his ear. "Louis, listen!"

Guy retold his story. Monsieur le Baron listened intently. So did the lady who had accompanied him. Guy felt that he told it very well, but for the second time he omitted all mention of that missing sheet of paper which had come into his possession. Monsieur le Baron was obviously much interested.

"You are quite sure—of the two men?" he asked quietly.

"Quite!" Guy answered confidently. "One was—"

Madame—Flossie's friend—dropped a wineglass. Monsieur le Baron raised his hand.

"No names," he said. "It is better not. We understand. A most interesting adventure, Monsieur Poynton, and—to your health!"

The wine was good, and the fun of the place itself went almost to the head. Always there were newcomers who passed down the room amidst a chorus of greetings, always the gayest of music. Then amidst cheers Flossie and another friend whom she called from a distant table danced a cake-walk—danced very gracefully, and with a marvellous display of rainbow skirts. She came back breathless, and threw herself down by Guy's side.

"Give me some more wine!" she panted. "How close the place is!"

The younger Frenchman, who had scarcely spoken, leaned over.

"An idea!" he exclaimed. "My automobile is outside. I will drive you all round the city. Monsieur Poynton shall see Paris undressed. Afterwards we will go to Louis' rooms and make his man cook us a déjeuner Anglais."

Flossie stood up and laughed.

"Who'll lend me a coat?" she cried. "I've nothing but a lace mantle."

"Plenty of Frenchmen in the car," the young Frenchman cried. "Are we all agreed? Good! Garçon, l'addition!"

"And mine," Guy ordered.

The women departed for their wraps. Guy and the two Frenchmen filled their pockets with cigarettes. When the bills came Guy found that his own was a trifle, and Monsieur Louis waved aside all protest.

"We are hosts to-night, my young friend," he declared with charming insistence. "Another time you shall have your turn. You must come round to the club to-morrow, and we will arrange for some sport. Allons!"

They crowded out together amidst a chorus of farewells. Guy took Flossie's arm going down the stairs.

"I say, I'm awfully obliged to you for introducing me to your friends," he declared. "I'm having a ripping time!"

She laughed.

"Oh, they're all right," she declared. "Mind my skirts!"

"I say, what does 'prenez garde' mean?" he asked.

"'Take care.' Why?"

He laughed again.

"Nothing!"

"Mademoiselle," the young man said, with an air of somewhat weary politeness, "I regret to say that there is nothing more to be done!"

He was grieved and polite because Mademoiselle was beautiful and in trouble. For the rest he was a little tired of her. Brothers of twenty-one, who have never been in Paris before, and cannot speak the language, must occasionally get lost, and the British Embassy is not exactly a transported Scotland Yard.

"Then," she declared, with a vigorous little stamp of her shapely foot, "I don't see what we keep an Ambassador here for at all—or any of you. It is scandalous!"

The Hon. Nigel Fergusson dropped his eyeglass and surveyed the young lady attentively.

"My dear Miss Poynton," he said, "I will not presume to argue with you. We are here, I suppose, for some purpose or other. Whether we fulfil it or not may well be a matter of opinion. But that purpose is certainly not to look after any young idiot—you must excuse my speaking plainly—who runs amuck in this most fascinating city. In your case the Chief has gone out of his way to help you. He has interviewed the chief of police himself, brought his influence to bear in various quarters, and I can tell you conscientiously that everything which possibly can be done is being done at the present moment. If you wish for my advice it is this: Send for some friend to keep you company here, and try to be patient. You are in all probability making yourself needlessly miserable."

She looked at him a little reproachfully. He noticed, however, with secret joy that she was drawing on her gloves.

"Patient! He was to meet me here ten days ago. He arrived at the hotel. His clothes are all there, and his bill unpaid. He went out the night of his arrival, and has never returned. Patient! Well, I am much obliged to you, Mr. Fergusson. I have no doubt that you have done all that your duty required. Good afternoon!"

"Good afternoon, Miss Poynton, and don't be too despondent. Remember that the French police are the cleverest in the world, and they are working for you."

She looked up at him scornfully.

"Police, indeed!" she answered. "Do you know that all they have done so far is to keep sending for me to go and look at dead bodies down at the Morgue? I think that I shall send over for an English detective."

"You might do worse," he answered; "but in any case, Miss Poynton, I do hope that you will send over for some friend or relation to keep you company. Paris is scarcely a fit place for you to be alone and in trouble."

"Thank you," she said. "I will remember what you have said."

The young man watched her depart with a curious mixture of relief and regret.

"The young fool's been the usual round, I suppose, and he's either too much ashamed of himself or too besotted to turn up. I wish she wasn't quite so devilish good-looking," he remarked to himself. "If she goes about alone she'll get badly scared before she's finished."

Phyllis Poynton drove straight back to her hotel and went to her room. A sympathetic chambermaid followed her in.

"Mademoiselle has news yet of her brother?" she inquired.

Mademoiselle shook her head. Indeed her face was sufficient answer.

"None at all, Marie."

The chambermaid closed the door.

"It would help Mademoiselle, perhaps, if she knew where the young gentleman spent the evening before he disappeared?" she inquired mysteriously.

"Of course! That is just what I want to find out."

Marie smiled.

"There is a young man here in the barber's shop, Mademoiselle," she announced. "He remembers Monsieur Poynton quite well. He went in there to be shaved, and he asked some questions. I think if Mademoiselle were to see him!"

The girl jumped up at once.

"Do you know his name?" she asked.

"Monsieur Alphonse, they call him. He is on duty now."

Phyllis< Poynton descended at once to the ground floor of the hotel, and pushed open the glass door which led into the coiffeur's shop. Monsieur Alphonse was waiting upon a customer, and she was given a chair. In a few minutes he descended the spiral iron staircase and desired to know Mademoiselle's pleasure.

"You speak English?" she asked.

"But certainly, Mademoiselle."

She gave a little sigh of relief.

"I wonder," she said, "if you remember waiting upon my brother last Thursday week. He was tall and fair, and something like me. He had just arrived in Paris."

Monsieur Alphonse smiled. He rarely forgot a face, and the young Englishman's tip had been munificent.

"Perfectly, Mademoiselle," he answered. "They sent for me because Monsieur spoke no French."

"My chambermaid, Marie, told me that you might perhaps know how he proposed to spend the evening," she continued. "He was quite a stranger in Paris, and he may have asked for some information."

Monsieur Alphonse smiled, and extended his hands.

"It is quite true," he answered. "He asked me where to go, and I say to the Folies Bergères. Then he said he had heard a good deal of the supper cafés, and he asked me which was the most amusing. I tell him the Café Montmartre. He wrote it down."

"Do you think that he meant to go there?" she asked.

"But certainly. He promised to come and tell me the next day how he amused himself."

"The Café Montmartre. Where is it?" she asked.

"In the Place de Montmartre. But Mademoiselle pardons—she will understand that it is a place for men."

"Are women not admitted?" she asked.

Alphonse smiled.

"But—yes. Only Mademoiselle understands that if a lady should go there she would need to be very well escorted."

She rose and slipped a coin into his hand.

"I am very much obliged to you," she said. "By the bye, have any other people made inquiries of you concerning my brother?"

"No one at all, Mademoiselle!" the man answered.

She almost slammed the door behind when she went out.

"And they say that the French police are the cleverest in the world," she exclaimed indignantly.

Monsieur Alphonse watched her through the glass pane.

"Ciel! But she is pretty!" he murmured to himself.

She turned into the writing-room, and taking off her gloves she wrote a letter. Her pretty fingers were innocent of rings, and her handwriting was a little shaky. Nevertheless, it is certain that not a man passed through the room who did not find an excuse to steal a second glance at her. This is what she wrote:—

"My dear Andrew,—

I am in great distress here, and very unhappy. I should have written to you before, but I know that you have your own trouble to bear just now, and I hated to bother you. I arrived here punctually on the date arranged upon between Guy and myself, and found that he had arrived the night before, and had engaged a room for me. He was out when I came. I changed my clothes and sat down to wait for him. He did not return. I made inquiries and found that he had left the hotel at eight o'clock the previous evening. To cut the matter short, ten days have now elapsed and he has not yet returned.

"I have been to the Embassy, to the police, and to the Morgue. Nowhere have I found the slightest trace of him. No one seems to take the least interest in his disappearance. The police shrug their shoulders, and look at me as though I ought to understand—he will return very shortly they are quite sure. At the Embassy they have begun to look upon me as a nuisance. The Morgue—Heaven send that I may one day forget the horror of my hasty visits there. I have come to the conclusion, Andrew, that I must search for him myself. How, I do not know; where, I do not know. But I shall not leave Paris until I have found him.

"Andrew, what I want is a friend here. A few months ago I should not have hesitated a moment to ask you to come to me. To-day that is impossible. Your presence here would only be an embarrassment to both of us. Do you know of any one who would come? I have not a single relative whom I can ask to help me. Would you advise me to write to Scotland Yard for a detective, or go to one of these agencies? If not, can you think of any one who would come here and help me, either for your sake as your friend, or, better still, a detective who can speak French and whom one can trust? All our lives Guy and I have congratulated ourselves that we have no relation nearer than India. I am finding out the other side of it now.

"I know that you will do what you can for me, Andrew. Write to me by return.

"Yours in great trouble and distress,

Phyllis Poynton."

She sealed and addressed her letter, and saw it despatched. Afterwards she crossed the courtyard to the restaurant, and did her best to eat some dinner. When she had finished it was only half-past eight. She rang for the lift and ascended to the fourth floor. On her way down the corridor a sudden thought struck her. She took a key from her pocket and entered the room which her brother had occupied.

His things were still lying about in some disorder, and neither of his trunks was locked. She went down on her knees and calmly proceeded to go through his belongings. It was rather a forlorn hope, but it seemed to her just possible that there might be in some of his pockets a letter which would throw light upon his disappearance. She found nothing of the sort, however. There were picture postcards, a few photographs, and a good many restaurant bills, but they were all from places in Germany and Austria. At the bottom of the second trunk, however, she found something which he had evidently considered it worth while to preserve carefully. It was a thick sheet of official-looking paper, bearing at the top an embossed crown, and covered with German writing. It was numbered at the top "seventeen," and it was evidently an odd sheet of some document. She folded it carefully up, and took it back with her to her own room. Then, with the help of a German dictionary, she commenced to study it. At the end of an hour she had made out a rough translation, which she read carefully through. When she had finished she was thoroughly perplexed. She had an uncomfortable sense of having come into touch with something wholly unexpected and mysterious.

"What am I to do?" she said to herself softly.

"What can it mean? Where on earth can Guy—have found this?"

There was no one to answer her, no one to advise. An overwhelming sense of her own loneliness brought the tears into her eyes. She sat for some time with her face buried in her hands. Then she rose up, calmly destroyed her translation with minute care, and locked away the mysterious sheet at the bottom of her dressing-bag. The more she thought of it the less, after all, she felt inclined to connect it with his disappearance.

Monsieur Albert looked over her shoulder for the man who must surely be in attendance—but he looked in vain.

"Mademoiselle wishes a table—for herself alone!" he repeated doubtfully.

"If you please," she answered.

It was obvious that Mademoiselle was of the class which does not frequent night cafés alone, but after all that was scarcely Monsieur Albert's concern. She came perhaps from that strange land of the free, whose daughters had long ago kicked over the barriers of sex with the same abandon that Mademoiselle Flossie would display the soles of her feet a few hours later in their national dance. If she had chanced to raise her veil no earthly persuasions on her part would have secured for her the freedom of that little room, for Monsieur Albert's appreciation of likeness was equal to his memory for faces. But it was not until she was comfortably ensconced at a corner table, from which she had a good view of the room, that she did so, and Monsieur Albert realized with a philosophic shrug of the shoulders the error he had committed.

Phyllis looked about her with some curiosity. It was too early for the habitués of the place, and most of the tables were empty. The scarlet-coated band were smoking cigarettes, and had not yet produced their instruments. The conductor curled his black moustache and stared hard at the beautiful young English lady, without, however, being able to attract a single glance in return. One or two men also tried to convey to her by smiles and glances the fact that her solitude need continue no longer than she chose. The unattached ladies put their heads together and discussed her with little peals of laughter. To all of these things she remained indifferent. She ordered a supper which she ate mechanically, and wine which she scarcely drank. All the while she was considering. Now that she was here what could she do? Of whom was she to make inquiries? She scanned the faces of the newcomers with a certain grave curiosity which puzzled them. She neither invited nor repelled notice. She remained entirely at her ease.

Monsieur Albert, during one of his peregrinations round the room, passed close to her table. She stopped him.

"I trust that Mademoiselle is well served!" he remarked with a little bow.

"Excellently, I thank you," she answered.

He would have passed on, but she detained him.

"You have very many visitors here," she remarked. "Is it the same always?"

He smiled.

"To-night," he declared, "it is nothing. There are many who come here every evening. They amuse themselves here."

"You have a good many strangers also?" she asked.

"But certainly," he declared. "All the time!"

"I have a brother," she said, "who was here eleven nights ago—let me see—that would be last Tuesday week. He is tall and fair, about twenty-one, and they say like me. I wonder if you remember him."

Monsieur Albert shook his head slowly.

"That is strange," he declared, "for as a rule I forget no one. Last Tuesday week I remember perfectly well. It was a quiet evening. La Scala was here—but of the rest no one. If Mademoiselle's brother was here it is most strange."

Her lip quivered for a moment. She was disappointed.

"I am so sorry," she said. "I hoped that you might have been able to help me. He left the Grand Hotel on that night with the intention of coming here—and he never returned. I have been very much worried ever since."

She was no great judge of character, but Monsieur Albert's sympathy did not impress her with its sincerity.

"If Mademoiselle desires," he said, "I will make inquiries amongst the waiters. I very much fear, however, that she will obtain no news here."

He departed, and Phyllis watched him talking to some of the waiters and the leader of the orchestra.

Presently he returned.

"I am very sorry," he announced, "but the brother of Mademoiselle could not have come here. I have inquired of the garçons, and of Monsieur Jules there, who forgets no one. They answer all the same."

"Thank you very much," she answered. "It must have been somewhere else!"

She was unreasonably disappointed. It had been a very slender chance, but at least it was something tangible. She had scarcely expected to have it snapped so soon and so thoroughly. She dropped her veil to hide the tears which she felt were not far from her eyes, and summoned the waiter for her bill. There seemed to be no object in staying longer. Suddenly the unexpected happened.

A hand, flashing with jewels, was rested for a moment upon her table. When it was withdrawn a scrap of paper remained there.

Phyllis looked up in amazement. The girl to whom the hand had belonged was sitting at the next table, but her head was turned away, and she seemed to be only concerned in watching the door. She drew the scrap of paper towards her and cautiously opened it. This is what she read, written in English, but with a foreign turn to most of the letters:—

"Monsieur Albert lied. Your brother was here. Wait till I speak to you."

Instinctively she crumpled up this strange little note in her hand. She struggled hard to maintain her composure. She had at once the idea that every one in the place was looking at her. Monsieur Albert, indeed, on his way down the room wondered what had driven the hopeless expression from her face.

The waiter brought her bill. She paid it and tipped him with prodigality which for a woman was almost reckless. Then she ordered coffee, and after a second's hesitation cigarettes. Why not? Nearly all the women were smoking, and she desired to pass for the moment as one of them. For the first time she ventured to gaze at her neighbor.

It was the young lady from Vienna. She was dressed in a wonderful demi-toilette of white lace, and she wore a large picture hat adjusted at exactly the right angle for her profile. From her throat and bosom there flashed the sparkle of many gems—the finger which held her cigarette was ablaze with diamonds. She leaned back in her seat smoking lazily, and she met Phyllis's furtive gaze with almost insolent coldness. But a moment later, when Monsieur Albert's back was turned, she leaned forward and addressed her rapidly.

"A man will come here," she said, "who could tell you, if he was willing, all that you seek to know. He will come to-night—he comes all the nights. You will see I hold my handkerchief so in my right hand. When he comes I shall drop it—so!"

The girl's swift speech, her half-fearful glances towards the door, puzzled Phyllis.

"Can you not come nearer to me and talk?" she asked.

"No! You must not speak to me again. You must not let any one, especially the man himself, know what I have told you. No more now. Watch for the handkerchief!"

"But what shall I say to him?"

The girl took no notice of her. She was looking in the opposite direction. She seemed to have edged away as far as possible from her. Phyllis drew a long breath.

She felt her heart beating with excitement. The place suddenly seemed to her like part of a nightmare.

And then all was clear again. Fortune was on her side. The secret of Guy's disappearance was in this room, and a few careless words from the girl at the next table had told her more than an entire police system had been able to discover. But why the mystery? What was she to say to the man when he came? The girl from Vienna was talking to some friends and toying carelessly with a little morsel of lace which she had drawn from her bosom. Phyllis watched it with the eyes of a cat. Every now and then she watched also the door.

The place was much fuller now. Mademoiselle Flossie had arrived with a small company of friends from Maxim's. The music was playing all the time. The popping of corks was almost incessant, the volume of sound had swelled. The laughter and greeting of friends betrayed more abandon than earlier in the evening. Old acquaintances had been renewed, and new ones made. Mademoiselle from Vienna was surrounded by a little circle of admirers. Still she held in her right hand a crumpled up little ball of lace.

Men passing down the room tried to attract the attention of the beautiful young English demoiselle who looked out upon the little scene so indifferently as regarded individuals, and yet with such eager interest as a whole. No one was bold enough, however, to make a second effort. Necessity at times gives birth to a swift capacity. Fresh from her simple country life, Phyllis found herself still able with effortless serenity to confound the most hardened boulevarders who paused to ogle her. Her eyes and lips expressed with ease the most convincing and absolute indifference to their approaches. A man may sometimes brave anger; he rarely has courage to combat indifference. So Phyllis held her own and waited.

And at last the handkerchief fell. Phyllis felt her own heart almost stop beating, as she gazed down the room. A man of medium height, dark, distinguished, was slowly approaching her, exchanging greetings on every side. His languid eyes fell upon Phyllis. Those who had watched her previously saw then a change. The cold indifference had vanished from her face. She leaned forward as though anxious to attract his attention. She succeeded easily enough.

He was almost opposite her table, and her half smile seemed to leave him but little choice. He touched the back of the chair which fronted hers, and took off his hat.

"Mademoiselle permits?" he asked softly.

"But certainly," she answered. "It is you for whom I have been waiting!"

"Mademoiselle flatters me!" he murmured, more than a little astonished.

"Not in the least," she answered. "I have been waiting to ask you what has become of my brother—Guy Poynton!"

He drew out the chair and seated himself. His eyes never left her face.

"Mademoiselle," he murmured, "this is most extraordinary!"

She noticed then that his hands were trembling.

"I am asking a great deal of you, George! I know it. But you see how helpless I am—and read the letter—read it for yourself."

He passed Phyllis's letter across the small round dining-table. His guest took it and read it carefully through.

"How old is the young lady?" he asked.

"Twenty-three!"

"And the boy?"

"Twenty-one."

"Orphans, I think you said?"

"Orphans and relationless."

"Well off?"

"Moderately."

Duncombe leaned back in his chair and sipped his port thoughtfully.

"It is an extraordinary situation!" he remarked.

"Extraordinary indeed," his friend assented. "But so far as I am concerned you can see how I am fixed. I am older than either of them, but I have always been their nearest neighbor and their most intimate friend. If ever they have needed advice they have come to me for it. If ever I have needed a day's shooting for myself or a friend I have gone to them. This Continental tour of theirs we discussed and planned out, months beforehand. If my misfortune had not come on just when it did I should have gone with them, and even up to the last we hoped that I might be able to go to Paris with Phyllis."

Duncombe nodded.

"Tell me about the boy," he said.

His host shrugged his shoulders.

"You know what they're like at that age," he remarked. "He was at Harrow, but he shied at college, and there was no one to insist upon his going. The pair of them had only a firm of lawyers for guardians. He's just a good-looking, clean-minded, high-spirited young fellow, full of beans, and needing the bit every now and then. But, of course, he's no different from the run of young fellows of his age, and if an adventure came his way I suppose he'd see it through."

"And the girl?"

Andrew Pelham rose from his seat.

"I will show you her photograph," he said.

He passed into an inner room divided from the dining-room by curtains. In a moment or two he reappeared.

"Here it is!" he said, and laid a picture upon the table.

Now Duncombe was a young man who prided himself a little on being unimpressionable. He took up the picture with a certain tolerant interest and examined it, at first without any special feeling. Yet in a moment or two he felt himself grateful for those great disfiguring glasses from behind which his host was temporarily, at least, blind to all that passed. A curious disturbance seemed to have passed into his blood. He felt his eyes brighten, and his breath come a little quicker, as he unconsciously created in his imagination the living presentment of the girl whose picture he was still holding. Tall she was, and slim, with a soft, white throat, and long, graceful neck; eyes rather darker than her complexion warranted, a little narrow, but bright as stars—a mouth with the divine lines of humor and understanding. It was only a picture, but a realization of the living image seemed to be creeping in upon him. He made the excuse of seeking a better light, and moved across to a distant lamp. He bent over the picture, but it was not the picture which he saw. He saw the girl herself, and even with the half-formed thought he saw her expression change. He saw her eyes lit with sorrow and appeal—he saw her arms outstretched towards him—he seemed even to hear her soft cry. He knew then what his answer would be to his friend's prayer. He thought no more of the excuses which he had been building in his mind; of all the practical suggestions which he had been prepared to make. Common-sense died away within him. The matter-of-fact man of thirty was ready to tread in the footsteps of this great predecessor, and play the modern knight-errant with the whole-heartedness of Don Quixote himself. He fancied himself by her side, and his heart leaped with joy of it. He thought no more of abandoned cricket matches and neglected house parties. A finger of fire had been laid upon his somewhat torpid flesh and blood.

"Well?" Andrew asked.

Duncombe returned to the table, and laid the picture down with a reluctance which he could scarcely conceal.

"Very nice photograph," he remarked. "Taken locally?"

"I took it myself," Andrew answered. "I used to be rather great at that sort of thing before—before my eyes went dicky."

Duncombe resumed his seat. He helped himself to another glass of wine.

"I presume," he said, "from the fact that you call yourself their nearest friend, that the young lady is not engaged?"

"No," Andrew answered slowly. "She is not engaged."

Something a little different in his voice caught his friend's attention. Duncombe eyed him keenly. He was conscious of a sense of apprehension. He leaned over the table.

"Do you mean, Andrew—?" he asked hoarsely. "Do you mean—?"

"Yes, I mean that," his friend answered quietly. "Nice sort of old fool, am I not? I'm twelve years older than she is, I'm only moderately well off and less than moderately good-looking. But after all I'm only human, and I've seen her grow up from a fresh, charming child into one of God's wonderful women. Even a gardener, you know, George, loves the roses he has planted and watched over. I've taught her a little and helped her a little, and I've watched her cross the borderland."

"Does she know?"

Andrew shook his head doubtfully.

"I think," he said, "that she was beginning to guess. Three months ago I should have spoken—but my trouble came. I didn't mean to tell you this, but perhaps it is as well that you should know. You can understand now what I am suffering. To think of her there alone almost maddens me."

Duncombe rose suddenly from his seat.

"Come out into the garden, Andrew," he said. "I feel stifled here."

His host rose and took Duncombe's arm. They passed out through the French window on to the gravel path which circled the cedar-shaded lawn. A shower had fallen barely an hour since, and the air was full of fresh delicate fragrance. Birds were singing in the dripping trees, blackbirds were busy in the grass. The perfume from the wet lilac shrubs was a very dream of sweetness. Andrew pointed across a park which sloped down to the garden boundary.

"Up there, amongst the elm trees, George," he said, "can you see a gleam of white? That is the Hall, just to the left of the rookery."

Duncombe nodded.

"Yes," he said, "I can see it."

"Guy and she walked down so often after dinner," he said quietly. "I have stood here and watched them. Sometimes she came alone. What a long time ago that seems!"

Duncombe's grip upon his arm tightened.

"Andrew," he said, "I can't go!"

There was a short silence. Andrew stood quite still. All around them was the soft weeping of dripping shrubs. An odorous whiff from the walled rose-garden floated down the air.

"I'm sorry, George! It's a lot to ask you, I know."

"It isn't that!"

Andrew turned his head toward his friend. The tone puzzled him.

"I don't understand."

"No wonder, old fellow! I don't understand myself."

There was another short silence. Andrew stood with his almost sightless eyes turned upon his friend, and Duncombe was looking up through the elm trees to the Hall. He was trying to fancy her as she must have appeared to this man who dwelt alone, walking down the meadow in the evening.

"No," he repeated softly, "I don't understand myself. You've known me for a long time, Andrew. You wouldn't write me down as altogether a sentimental ass, would you?"

"I should not, George. I should never even use the word 'sentimental' in connection with you."

Duncombe turned and faced him squarely. He laid his hands upon his friend's shoulders.

"Old man," he said, "here's the truth. So far as a man can be said to have lost his heart without rhyme or reason, I've lost mine to the girl of that picture."

Andrew drew a quick breath.

"Rubbish, George!" he exclaimed. "Why, you never saw her. You don't know her!"

"It is quite true," Duncombe answered. "And yet—I have seen her picture."

His friend laughed queerly.

"You, George Duncombe, in love with a picture. Stony-hearted George, we used to call you. I can't believe it! I can't take you seriously. It's all rot, you know, isn't it! It must be rot!"

"It sounds like it," Duncombe answered quietly. "Put it this way, if you like. I have seen a picture of the woman whom, if ever I meet, I most surely shall love. What there is that speaks to me from that picture I do not know. You say that only love can beget love. Then there is that in the picture which points beyond. You see, I have talked like this in an attempt to be honest. You have told me that you care for her. Therefore I have told you these strange things. Now do you wish me to go to Paris, for if you say yes I shall surely go!"

Again Andrew laughed, and this time his mirth sounded more natural.

"Let me see," he said. "We drank Pontet Canet for dinner. You refused liqueurs, but I think you drank two glasses of port. George, what has come over you? What has stirred your slow-moving blood to fancies like these? Bah! We are playing with one another. Listen! For the sake of our friendship, George, I beg you to grant me this great favor. Go to Paris to-morrow and help Phyllis!"

"You mean it?"

"God knows I do. If ever I took you seriously, George—if ever I feared to lose the woman I love—well, I should be a coward for my own sake to rob her of help when she needs it so greatly. Be her friend, George, and mine. For the rest the fates must provide!"

"The fates!" Duncombe answered. "Ay, it seems to me that they have been busy about my head to-night. It is settled, then. I will go!"

At precisely half-past nine on the following evening Duncombe alighted from his petite voiture in the courtyard of the Grand Hotel, and making his way into the office engaged a room. And then he asked the question which a hundred times on the way over he had imagined himself asking. A man to whom nervousness in any shape was almost unknown, he found himself only able to control his voice and manner with the greatest difficulty. In a few moments he might see her.

"You have a young English lady—Miss Poynton—staying here, I believe," he said. "Can you tell me if she is in now?"

The clerk looked at him with sudden interest.

"Miss Poynton is staying here, sir," he said. "I do not believe that she is in just now. Will you wait one moment?"

He disappeared rapidly, and was absent for several minutes. When he returned he came out into the reception hall.

"The manager would be much obliged if you would step into his office for a moment, sir," he said confidentially. "Will you come this way?"

Duncombe followed him into a small room behind the counter. A gray-haired man rose from his desk and saluted him courteously.

"Sir George Duncombe, I believe," he said. "Will you kindly take a seat?"

Duncombe did as he was asked. All the time he felt that the manager was scrutinizing him curiously.

"Your clerk," he said, "told me that you wished to speak to me."

"Exactly!" the manager answered. "You inquired when you came in for Miss Poynton. May I ask—are you a friend of hers?"

"I am here on behalf of her friends," Duncombe answered. "I have letters to her."

The manager bowed gravely.

"I trust," he said, "that you will soon have an opportunity to deliver them. We are not, of course, responsible in any way for the conduct or doings of our clients here, but I am bound to say that both the young people of the name you mention have been the cause of much anxiety to us."

"What do you mean?" Duncombe asked quickly.

"Mr. Guy Poynton," the manager continued, "arrived here about three weeks ago, and took a room for himself and one for his sister, who was to arrive on the following day. He went out that same evening, and has never since returned. Of that fact you are no doubt aware."

Duncombe nodded impatiently.

"Yes!" he said. "That is why I am here."

"His sister arrived on the following day, and was naturally very distressed. We did all that we could for her. We put her in the way of communicating with the police and the Embassy here, and we gave her every assistance that was possible. Four nights ago Mademoiselle went out late. Since then we have seen nothing of her. Mademoiselle also has disappeared."

Duncombe sprang to his feet. He was suddenly pale.

"Good God!" he exclaimed. "Four nights ago! She went out alone, you say?"

"How else? She had no friends here. Once or twice at my suggestion she had taken one of our guides with her, but she discontinued this as she fancied that it made her conspicuous. She was all the time going round to places making inquiries about her brother."

Duncombe felt himself suddenly precipitated into a new world—a nightmare of horrors. He was no stranger in the city, and grim possibilities unfolded themselves before his eyes. Four nights ago!

"You have sent—to the police?"

"Naturally. But in Paris—Monsieur must excuse me if I speak plainly—a disappearance of this sort is never regarded seriously by them. You know the life here without doubt, Monsieur! Your accent proves that you are well acquainted with the city. No doubt their conclusions are based upon direct observation, and in most cases are correct—but it is very certain that Monsieur the Superintendent regards such disappearances as these as due to one cause only."

Duncombe frowned, and something flashed in his eyes which made the manager very glad that he had not put forward this suggestion on his own account.

"With regard to the boy," he said, "this might be likely enough. But with regard to the young lady it is of course wildly preposterous. I will go to the police myself," he added, rising.

"One moment, Sir George," the manager continued. "The disappearance of the young lady was a source of much trouble to me, and I made all possible inquiries within the hotel. I found that on the day of her disappearance Mademoiselle had been told by one of the attendants in the barber's shop, who had waited upon her brother on the night of his arrival, that he—Monsieur Guy—had asked for the name of some cafés for supper, and that he had recommended Café Montmartre. Mademoiselle appears to have decided to go there herself to make inquiries. We have no doubt that when she left the hotel on the night of her disappearance it was to there that she went."

"You have told the police this?"

"Yes, I have told them," the manager answered dryly. "Here is their latest report, if you care to see it."

Duncombe took the little slip of paper and read it hastily.

Disappearance of Mademoiselle Poynton, from England.—

We regret to state no trace has been discovered of the missing young lady.

(Signed) Jules Legarde, Superintendent.

"That was only issued a few hours ago," the manager said.

"And I thought," Duncombe said bitterly, "that the French police were the best in the world!"

The manager said nothing. Duncombe rose from his chair.

"I shall go myself to the Café Montmartre," he said. The manager bowed.

"I shall be glad," he said, "to divest myself of any further responsibility in this matter. It has been a source of much anxiety to the directors as well as myself."

Duncombe walked out of the room, and putting on his coat again called for a petite voiture. He gave the man the address in the Rue St. Honoré and was driven to a block of flats there over some shops.

"Is Monsieur Spencer in?" he asked the concierge. He was directed to the first floor. An English man-servant admitted him, and a few moments later he was shaking hands with a man who was seated before a table covered with loose sheets of paper.

"Duncombe, by all that's wonderful!" he exclaimed, holding out his hand. "Why, I thought that you had shaken the dust of the city from your feet forever, and turned country squire. Sit down! What will you have?"

"First of all, am I disturbing you?"

Spencer shook his head.

"I've no Press work to-night," he answered. "I've a clear hour to give you at any rate. When did you come?"

"Two-twenty from Charing Cross," Duncombe answered. "I can't tell you how thankful I am to find you in, Spencer. I'm over on a very serious matter, and I want your advice."

Spencer touched the bell. Cigars and cigarettes, whisky and soda, appeared as though by magic.

"Now help yourself and go ahead, old chap," his host declared. "I'm a good listener."

He proved himself so, sitting with half-closed eyes and an air of close attention until he had heard the whole story. He did not once interrupt, but when Duncombe had finished he asked a question.

"What did you say was the name of this café where the boy had disappeared?"

"Café Montmartre."

Spencer sat up in his chair. His expression had changed.

"The devil!" he murmured softly.

"You know the place?"

"Very well. It has an extraordinary reputation. I am sorry to say it, Duncombe, but it is a very bad place for your friend to have disappeared from."

"Why?"

"In the first place it is the resort of a good many of the most dangerous people in Europe—people who play the game through to the end. It is a perfect hot-bed of political intrigue, and it is under police protection."

"Police protection! A place like that!" Duncombe exclaimed.

"Not as you and I understand it, perhaps," Spencer explained. "There is no Scotland Yard extending a protecting arm over the place, and that sort of thing. But the place is haunted by spies, and there are intrigues carried on there in which the secret service police often take a hand. In return it is generally very hard to get to the bottom of any disappearance or even robbery there through the usual channels. To the casual visitor, and of course it attracts thousands from its reputation, it presents no more dangers perhaps than the ordinary night café of its sort. But I could think of a dozen men in Paris to-day, who, if they entered it, I honestly believe would never be seen again."

Spencer was exaggerating, Duncombe murmured to himself. He was a newspaper correspondent, and he saw these things with the halo of melodrama around them. And yet—four nights ago. His face was white and haggard.

"The boy," he said, "could have been no more than an ordinary visitor. He had no great sum of money with him, he had no secrets, he did not even speak the language. Surely he would have been too small fry for the intriguers of such a place!"

"One would think so," Spencer answered musingly. "You are sure that he was only what you say?"

"He was barely twenty-one," Duncombe answered, "and he had never been out of England before."

"What about the girl?"

"She is two years older. It was her first visit to Paris." Spencer nodded.

"The disappearance of the boy is of course the riddle," he remarked. "If you solve that you arrive also at his sister's whereabouts. Upon my word, it is a poser. If it had been the boy alone—well, one could understand. The most beautiful ladies in Paris are at the Montmartre. No one is admitted who is not what they consider—chic! The great dancers and actresses are given handsome presents to show themselves there. On a representative evening it is probably the most brilliant little roomful in Europe. The boy of course might have lost his head easily enough, and then been ashamed to face his sister. But when you tell me of her disappearance, too, you confound me utterly. Is she good-looking?"

"Very!"

"She would go there, of course, asking for her brother," Spencer continued thoughtfully. "An utterly absurd thing to do, but no doubt she did, and—look here, Duncombe, I tell you what I'll do. I have my own two news-grabbers at hand, and nothing particular for them to do this evening. I'll send them up to the Café Montmartre."

"It's awfully good of you, Spencer. I was going myself," Duncombe said, a little doubtfully.

"You idiot!" his friend said cheerfully, yet with a certain emphasis. "English from your hair to your boots, you'd go in there and attempt to pump people who have been playing the game all their lives, and who would give you exactly what information suited their books. They'd know what you were there for, the moment you opened your mouth. Honestly, what manner of good do you think that you could do? You'd learn what they chose to tell you. If there's really anything serious behind all this, do you suppose it would be the truth?"

"You're quite right, I suppose," Duncombe admitted, "but it seems beastly to be doing nothing."

"Better be doing nothing than doing harm!" Spencer declared. "Look round the other cafés and the boulevards. And come here at eleven to-morrow morning. We'll breakfast together at Paillard's."

Spencer wrote out his luncheon with the extreme care of the man to whom eating has passed to its proper place amongst the arts, and left to Duncombe the momentous question of red wine or white. Finally, he leaned back in his chair, and looked thoughtfully across at his companion.

"Sir George," he said, "you have placed me in a very painful position."

Duncombe glanced up from his hors d'œuvre.

"What do you mean?"

"I will explain," Spencer continued. "You came to me last night with a story in which I hope that I showed a reasonable amount of interest, but in which, as a matter of fact, I was not interested at all. Girls and boys who come to Paris for the first time in their lives unattended, and find their way to the Café Montmartre, and such places, generally end up in the same place. It would have sounded brutal if I had added to your distress last night by talking like this, so I determined to put you in the way of finding out for yourself. I sent two of my most successful news-scouts to that place last night, and I had not the slightest doubt as to the nature of the information which they would bring back. It turns out that I was mistaken."

"What did they discover?" Duncombe asked eagerly.

"Nothing!"

Duncombe's face fell, but he looked a little puzzled.

"Nothing? I don't understand. They must have heard that they had been there anyhow."

"They discovered nothing. You do not understand the significance of this. I do! It means that I was mistaken for one thing. Their disappearance has more in it than the usual significance. Evil may have come to them, but not the ordinary sort of evil. Listen! You say that the police have disappointed you in having discovered nothing. That is no longer extraordinary to me. The police, or those who stand behind them, are interested in this case, and in the withholding of information concerning it."

"You are talking riddles to me, Spencer," Duncombe declared. "Do you mean that the police in Paris may become the hired tools of malefactors?"

"Not altogether that," Spencer said, waving aside a dish presented before him by the head waiter himself with a gesture of approval. "Not necessarily malefactors. But there are other powers to be taken into consideration, and most unaccountably your two friends are in deeper water than your story led me to expect. Now, not another question, please, until you have tried that sauce. Absolute silence, if you please, for at least three or four minutes."

Duncombe obeyed with an ill grace. He had little curiosity as to its flavor, and a very small appetite at all with the conversation in its present position. He waited for the stipulated time, however, and then leaned once more across the table.

"Spencer!"

"First I must have your judgment upon the sauce. Did you find enough mussels?"

"Damn the sauce!" Duncombe answered. "Forgive me, Spencer, but this affair is, after all, a serious one to me. You say that your two scouts, as you call them, discovered nothing. Well, they had only one evening at it. Will they try again in other directions? Can I engage them to work for me? Money is absolutely no object."

Spencer shook his head.

"Duncombe," he said, "you're going to think me a poor sort of friend, but the truth is best. You must not count upon me any more. I cannot lift even my little finger to help you. I can only give you advice if you want it."

"And that?"

"Go back to England to-morrow. Chuck it altogether. You are up against too big a combination. You can do no one any good. You are a great deal more likely to come to harm yourself."

Duncombe was quite quiet for several moments. When he spoke again his manner had a new stiffness.

"You have surprised me a good deal, I must confess, Spencer. We will abandon the subject."

Spencer shrugged his shoulders.

"I know how you're feeling, old chap," he said. "I can't help it. You understand my position here. I write a daily letter for the best paying and most generous newspaper in the world, and it is absolutely necessary that I keep hand in glove with the people in high places here. My position absolutely demands it, and my duty to my chief necessitates my putting all personal feeling on one side in a case like this when a conflict arises."

"But where," Duncombe asked, "does the conflict arise?"

"Here!" Spencer answered. "I received a note this morning from a great personage in this country to whom I am under more obligation than any other breathing man, requesting me to refrain from making any further inquiries or assisting any one else to make them in this matter. I can assure you that I was thunderstruck, but the note is in my pocket at the present moment."

"Does it mention them by name?"

"The exact words are," Spencer answered, "'respecting the reported disappearance of the young Englishman, Mr. Guy Poynton, and his sister.' This will just show you how much you have to hope for from the police, for the person whose signature is at the foot of that note could command the implicit obedience of the whole system."

Duncombe's cheeks were a little flushed. He was British to the backbone, and his obstinacy was being stirred.

"The more reason," he said quietly, "so far as I can see, that I should continue my independent efforts with such help as I can secure. This girl and boy are fellow country-people, and I haven't any intention of leaving them in the clutches of any brutal gang of Frenchmen into whose hands they may have got. I shall go on doing what I can, Spencer."

The journalist shrugged his shoulders.

"I can't help sympathizing with you, Duncombe," he said, "but keep reasonable. You know your Paris well enough to understand that you haven't a thousand to one chance. Besides, Frenchmen are not brutal. If the boy got into a scrape, it was probably his own fault."

"And the girl? What of her? Am I to leave her to the tender mercies of whatever particular crew of blackguards may have got her into their power?"

"You are needlessly melodramatic," Spencer answered. "I will admit, of course, that her position may be an unfortunate one, but the personage whom I have the honor to call my friend does not often protect blackguards. Be reasonable, Duncombe! These young people are not relatives of yours, are they?"

"No!"

"Nor very old friends? The young lady, for instance?"

Duncombe looked up, and his face was set in grim and dogged lines. He felt like a man who was nailing his colors to the mast.

"The young lady," he said, "is, I pray Heaven, my future wife!"

Spencer was honestly amazed, and a little shocked.

"Forgive me, Duncombe," he said. "I had no idea—though perhaps I ought to have guessed."

They went on with their luncheon in silence for some time, except for a few general remarks. But after the coffee had been brought and the cigarettes were alight, Spencer leaned once more across the table.

"Tell me, Duncombe, what you mean to do."

"I shall go to the Café Montmartre myself to-night. At such a place there must be hangers-on and parasites who see something of the game. I shall try to come into touch with them. I am rich enough to outbid the others who exact their silence."

"You must be rich enough to buy their lives then," Spencer answered gravely, "for if you do succeed in tempting any one to betray the inner happenings of that place on which the seal of silence has been put, you will hear of them in the Morgue before a fortnight has passed."

"They must take their risk," Duncombe said coldly. "I am going to stuff my pockets with money to-night, and I shall bid high. I shall leave word at the hotel where I am going. If anything happens to me there—well, I don't think the Café Montmartre will flourish afterwards."

"Duncombe," his friend said gravely, "nothing will happen to you at the Café Montmartre. Nothing ever does happen to any one there. You remember poor De Laurson?"

"Quite well. He was stabbed by a girl in the Rue Pigalle."

"He was stabbed in the Café Montmartre, but his body was found in the Rue Pigalle. Then there was the Vicomte de Sauvinac."

"He was found dead in his study—poisoned."

"He was found there—yes, but the poison was given to him in the Café Montmartre, and it was there that he died. I am behind the scenes in some of these matters, but I know enough to hold my tongue, or my London letter wouldn't be worth a pound a week. I am giving myself away to you now, Duncombe. I am risking a position which it has taken me twenty years to secure. I've got to tell you these things, and you must do as I tell you. Go back to London!"

Duncombe laughed as he rose to his feet.

"Not though the Vicomte's fate is to be mine to-night," he answered. "The worse hell this place is the worse the crew it must shelter. I should never hold my head up again if I sneaked off home and left the girl in their hands. I don't see how you can even suggest it."

"Only because you can't do the least good," Spencer answered. "And besides, don't run away with a false impression. The place is dangerous only for certain people. The authorities don't protect murderers or thieves except under special circumstances. The Vicomte's murderer and De Laurson's were brought to justice. Only they keep the name of the place out of it always. Tourists in shoals visit it, and visit safely every evening. They pay fancy prices for what they have, but I think they get their money's worth. But for certain classes of people it is the decoy house of Europe. Foreign spies have babbled away their secrets there, and the greatest criminals of the world have whispered away their lives to some fair daughter of Judas at those tables. I, who am behind the scenes, tell you these things, Duncombe."

Duncombe smiled.

"To-morrow," he said, "you may add another victim to your chamber of horrors!"

The amber wine fell in a little wavering stream from his upraised glass on to the table-cloth below. He leaned back in his chair and gazed at his three guests with a fatuous smile. The girl in blue, with the dazzlingly fair hair and wonderful complexion, steadied his hand and exchanged a meaning look with the man who sat opposite. Surely the poor fool was ready for the plucking? But Madame, who sat beside her, frowned upon them both. She had seen things which had puzzled her. She signed to them to wait.

She leaned over and flashed her great black eyes upon him.

"Monsieur enjoys himself like this every night in Paris?"

A soft, a very seductive, voice. The woman who envied her success compared it to the purring of a cat. Men as a rule found no fault with it, especially those who heard it for the first time.

Duncombe set down his glass, now almost empty. He looked from the stain on the table-cloth into the eyes of Madame, and again she thought them very unlike the eyes of a drunken man.

"Why not? It's the one city in the world to enjoy one's self in. Half-past four, and here we are as jolly as anything. Chucked out of everywhere in London at half-past twelve. 'Time, gentlemen, please!' And out go the lights. Jove, I wonder what they'd think of this at the Continental! Let's—let's have another bottle."

The fair-haired girl—Flossie to her friends, Mademoiselle Mermillon until you had been introduced—whispered in his ear. He shook his head vaguely. She had her arm round his neck. He removed it gently.

"We'll have another here first anyhow," he declared. "Hi, Garçon! Ring the bell, there's a good chap, Monsieur—dash it, I've forgotten your name. No, don't move. I'll do it myself."

He rose and staggered towards the door.

"The bell isn't that way, Monsieur," Madame exclaimed. "It is to the right. Louis, quick!"

Monsieur Louis sprang to his feet. There was a queer grating little sound, followed by a sharp click. Duncombe had swung round and faced them. He had turned the key in the door, and was calmly pocketing it. The hand which held that small shining revolver was certainly not the hand of a drunken man.

They all three looked at him in wonder—Madame, Monsieur Louis, and Mademoiselle Flossie. The dark eyebrows of Madame almost met, and her eyes were full of the promise of evil things. Monsieur Louis, cowering back from that steadily pointed revolver, was white with the inherited cowardice of the degenerate. Flossie, who had drunk more wine than any of them, was trying to look as though it were a joke. Duncombe, with his disordered evening clothes, his stained shirt-front and errant tie, was master of the situation. He came and stood a few feet away from them. His blundering French accent and slow choice of words had departed. He spoke to them without hesitation, and his French was almost as good as their own.

"I want you to keep your places," he said, "and listen to me for a few minutes. I can assure you I am neither mad nor drunk. I have a few questions to ask you, and if your answers are satisfactory you may yet find my acquaintance as profitable as though I had been the pigeon I seemed. Keep your seat, Monsieur le Baron!"

Monsieur Louis, who had half risen, sat down again hastily. They all watched him from their places around the table. It was Madame whom he addressed more directly—Madame with the jet black hair and golden earrings, the pale cheeks and scarlet lips.

"I invited you into a private room here," he said, "because what I have said to you three is between ourselves alone. You came, I presume, because it promised to be profitable. All that I want from you is information. And for that I am willing to pay."