RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Administered by Matthias Kaether and Roy Glashan

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

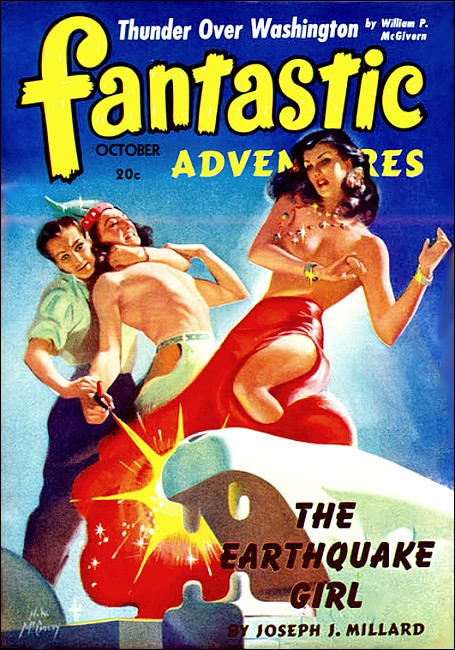

Fantastic Adventures, October 1941, with "The Truthful Liar"

Major Marquand wheeled in time to see Ying slump to the sidewalk.

"THEN you will not reconsider, Major Marquand?" the little oriental pleaded. "You will have no change of heart?"

The tall, moustached man smiled contemptuously.

"I have told you, Ying, that you are a fool. The money is gone, and that's all there is to it. Unfortunate, but final." He turned away, as if to leave. The little oriental reached forth and put a detaining hand on his arm.

"That money," Ying said softly, "was for war relief of my people. It meant food and clothing and bandages and medicines for the poor and the weak and helpless."

"You should have thought of that," Major Marquand declared with bland unconcern, "before you risked it. After all, your people trusted you to handle the funds."

"But you told me that I was not risking it. You told me that it was a foolproof investment which would bring returns for my people's money!" Ying was fighting hard to keep his voice level.

"There is no such thing as a foolproof investment," Major Marquand smiled. "You know this by now. What happened was unfortunate. But I can do nothing about it. Now, if you please, I'll say goodbye. Perhaps we'll meet again and laugh over this misfortune." Once more Major Marquand turned to leave, and once more Ying seized his arm.

"In the legends of my people, Major Marquand, there is a very ancient incantation. It has been used only against those of your stripe." Ying half closed his eyes, and recited, almost inaudibly, "May the Gods of Truth control your lies against you; and through the hours of this day, may the demons of hell follow the untruths from your foul tongue!"

Major Marquand smiled mockingly.

"Very pretty," he applauded. "Now, Ying, get off the steps of this hotel. And if you bother me with so much as a visit again, I'll have you thrown out. Good day!"

Major Marquand was at the door of the hotel, just stepping toward his cab, when the pistol shot rang out. By the time he had wheeled, to stare down the sidewalk, a tiny knot of horrified pedestrians had gathered around the body of Ying. The little oriental had put a bullet through his brain.

IN the cocktail bar of the Hotel Carlo, late that afternoon, Major Milo Marquand, tanned, virile, and immaculately tailored in a fresh suit of whites, sat in pleasant contemplation sipping a brandy.

The affair of the suicide was now almost forgotten. At least it was buried among the unpleasant trifles of the day. The management of the hotel had been very swift and efficient in ridding Major Marquand of the bother of a police report investigation. They realized that a guest as important as the Major would think kindly toward them for it.

The major smiled at his reflection in the mirror behind the bar, fully realizing what a militarily handsome figure he presented. His appearance was his greatest stock in trade. That slight scar at his jaw, for example, could pass with quiet modesty as the souvenir he had obtained in the Arabian fighting. This, in spite of the fact that the scar had been obtained on the sharp edge of a beer bottle in a fight in Hell's Kitchen while a youth.

And the slight Roman ridge in his nose—patrician though it looked—was a reminder of an unpleasant three years spent in the state reformatory. He'd gotten it stealing from a cell-mate.

But that and other murky outlines of his past were all behind him now. For Major Milo Marquand—christened by his drunken mother as Nicki Moretti—was a very wealthy man. In fact this stay at the expensive Hotel Carlo was in celebration of his recent attainment of seventy-five thousand dollars.

The seventy-five grand should see him through at least three years of good living. Three years in which he could do a lot of traveling, and let his scent cool off quite a bit. Not that the cops were hot after him, he told himself again, but in the "con" game a person is wise to lay low after a big killing.

And the war relief funds swindled from the guileless Ying had been a plenty big killing—and safe. The major had counted on Ying's shame to keep the little oriental's mouth shut. And the suicide, rather than face his people, was more than the major had dared hope for. Now everything was right. The major ordered another drink in honor of Ying.

It would be good to take a rest, the major thought happily. But he couldn't resist stooping to flip the bartender for double-or-nothing on the drink. Just a sporting gesture from a grand gentleman to a servant. And when the grand gentleman, Major Marquand, had won, he put his two-headed half dollar back in his pocket and smiled benignly on the servant bartender.

The bar had been deserted save for the major and the tender, but now a short, pudgy, leather skinned man of middle age entered and took a stool beside Marquand. Instantly and instinctively—from long practice—the major sized up the newcomer.

THE man was wearing expensive clothes that were, nevertheless, baggy and ill-fitting. The hide color of his skin marked him as being from the west or southwestern States.

"Cow money," the major thought. "Or oil." He smiled engagingly at the pudgy little man, also a habit of long practice.

"Have a drink with me, sir," the major said, putting on his best, slightly British accent.

The newcomer looked up, startled and pleased.

"Well, that's right nice of you, stranger," he said. His drawl scored the major's first guess as to origin a hundred per cent. "Don't mind if I do."

The bartender took the newcomer's order, straight rye and went off to get the bottle, smiling fondly at the major's democratic ways.

"You look like a Texan," the major declared after a moment.

The newcomer grinned.

"Not so far off, at that. I hail from Oklahoma. My name's Scragg. What's yours?" He held out a hand that wasn't pudgy, but was brown and hard.

The major gave him a firm military grip and his name.

"Well, now," said Scragg. "A fighting man, eh?"

The major smiled modestly.

"Hardly, old chap. That is, not any more. I saw a bit of service back awhile." Then, easily, "Are you traveling on business, or just on vacation?"

"Well," Scragg seemed to appraise the major for an instant as if debating whether or not he should immediately take him into close confidence. The major smiled, melting Scragg's conversational ice jam. "Well," he went on, "a little bit of both. You see Ma and I—always call the Missus Ma—Ma and I have got to go down to Saint Looie to clear out the rest of her father's estate. Sell property and all like that. Her pop passed away about six months back. Left her quite a bit he'd made on okie oil speculations in the past five years."

Something inside Major Marquand reacted like a fire gong on an engine horse. In spite of his resolve to keep strictly away from business, he found himself mentally scratching his itchy palms.

"Oil speculations are deucedly interesting," Major Marquand fished. "Had a bit of a go with oil speculations in Iraq, some years back. Just dabbled, y'know."

"Did you now?" Scragg was pleased at finding a common bond with this obviously high-toned stranger. "Then you'll be interested in hearing about our wells, the ones the Missus' pop left to her."

"Right now," said Major Marquand, "I hold nothing but South African mining interests, but you've no idea how much your oil talk will interest me."

"Mines, eh?" said Scragg, duly impressed. "Bartender, get this here major gentleman what he wants to drink." And then, volubly, and in great detail, Mr. Scragg sailed into a complete accounting of his oil wells. And as Scragg talked on, Major Marquand bought drink after drink, for some of which he flipped his two-headed half dollar with the bartender.

AT the end of an hour, Scragg had exhausted his oil information. And at the end of that time, Major Marquand was exultantly certain that this fish had at least two-hundred-thousand dollars of ready cash waiting to find a smarter pocket. The temptation was terrible. Something in the back of his brain kept hinting to the major that this was too good to pass up, and that luck runs in cycles, and that he was swinging into the peak of his cycle. At length, Major Marquand gave way to temptation. He began to talk about his South African mining holdings.

"Diamonds," said Scragg, properly awed. "There must be a fortune in diamonds!"

Major Marquand smiled deprecatingly.

"Not so much as you'd think there was," he said. "Why, I've one mine on which the yearly yield is only a hundred thousand."

Major Marquand picked this time as appropriate for tipping the bartender a fiver with the round of drinks he brought up. Any doubts that Scragg might have held as to the actual worth of the mine promptly vanished.

"How many mines do you have?" Scragg asked almost breathlessly.

"There now," the major laughed at himself, "I've started trying to pass myself off as a chap of great wealth. To be utterly frank, old boy, it's not as big as it sounds. You see, I've only three mines. Each is in the same territory."

Scragg took a deep breath, opened his mouth, swallowed the hook, and was on. From that moment, Major Marquand felt certain he had him. They left the bar two hours later, parting in front of the main desk of the hotel.

"And I want you and your wife to be my guests at dinner this evening," the major reminded Scragg.

Scragg was starry-eyed.

"I don't know how I'll ever repay you, Major," he declared a bit thickly. "Your a white man, certain. That transaction is all in my favor. I feel as if me and Ma was cheating you blind."

The major waved his hand.

"Don't be silly. I've a hunch I can make oil pay me something. It'll be fun trying, at the least." Then he turned to the desk clerk.

"I'll be expecting a cable for the Maharajah of Ejkar in the next hour or so. Will you see that it's sent up to my room promptly, boy?"

Scragg looked at the major as if he might swoon with excitement.

"One of them Indian Prince fellows?" he asked.

"An old friend," the major nodded. "We play chess by cable. He might not have figured out his move yet, but I expect to hear from him soon."

Scragg extended his hand.

"Until dinner, Major," he said.

"Until dinner, Mr. Scragg."

"Call me George," Mr. Scragg begged.

The major smiled fondly.

"I've not many friends, George. But I've certainly taken a liking to you, old chap." It was like patting a puppy on the head. Scragg walked off in a daze of pride. The major watched him go. Then he turned to the desk clerk. "I'm also expecting a carton of Fielding-Nought cigarettes from New York. My special brand. If they arrive, send them up."

Fielding-Noughts were a dollar the package. Major Marquand strolled to the elevators happy in the knowledge that everything was running smoothly. Two-hundred-seventy-five grand would be so much nicer than a mere seventy-five. Already the major was a little bit disgusted with himself for having been so easily satisfied.

IN his luxurious suite of rooms, the major opened his luggage and rummaged back and forth until he finally located the papers he wanted: his South African mining deeds. He looked at them fondly as he put them atop his bureau. He'd never imagined he'd use these again. They'd been good in nailing lots of small fry in the old days. And the major's judgment of George Scragg placed the Oklahoman as being

distinctively small fry, but with big-time cash reserves.

The major smiled, recalling the latter part of the conversation at the bar. Two-hundred-thousand cash, in exchange for a stinking old hole in the earth that hadn't produced a Woolworth imitation in the last eighty years. It was a slick job, even though he wouldn't have had to have been so slick with such an easy snipe as Scragg. But, being a professional, the major took pride in doing his work well.

"Tonight I'll get the check. Cash it tomorrow; gone the following day. And Scragg will wake up two weeks later." The major mused pleasantly to himself. There were plenty of far-off places to be reached by plane in that time.

There was a knocking on his door. The major looked up.

"Come in, old chap," he shouted.

A bellhop entered.

"Cablegram," he said.

For an instant Major Marquand permitted a frown to slip across his brows. Then it was gone and he took the envelope with careless unconcern, tossing a half-dollar on the tray. The boy left.

Feverishly, then, Major Marquand tore open the cable. This was a gag of some sort. Who in the hell would be sending him a cable? He didn't know a soul who lived outside of the Uni—Major Marquand cursed in explosive bewilderment.

The cable contained chess symbols.

And it was signed: "Maharajah of Ejkar!"

The major's hand trembled ever so lightly. If this were a gag, and it had to be a gag since, as far as he knew, there wasn't any such person as the Maharajah of Ejkar, it was definitely screwy.

Then the major's jaws hardened. It was a gag, of course. Why, it was all it could be. Doubtless there was another "con" here at the Hotel Carlo who must have recognized him in the lobby. All right. It was funny and he'd let it go. Just so long as that other "con," whoever he was, kept his mitts off Scragg.

It was hard for the major to drive away the unnerving effects of the fake cable as he crumpled it up and tossed it in the waste basket. And it was harder still for him to sleep as he stretched out on his bed for a short nap.

Especially when another bellhop appeared less than a half hour later—bearing a long, oblong, sealed carton, postmarked, "New York."

The major was so nettled this time that he forgot to tip the bellhop, and sent him away with an uncivil grunt. For on the top of the package there was the label, "Fielding-Nought."

This was unnerving because of the fact that Major Marquand had never placed such an order with those cigarette manufacturers. And he was additionally bewildered when, on opening the package at the top of those in the carton, he saw that the long, fine tobaccoed cigarettes bore in gold lettering the name: "Major Milo Marquand!"

The major threw the carton angrily on the sofa.

"This is going a little far, whoever that wise guy happens to be."

And it occurred to him then that it might be a wise idea to look up his heckler and offer to make a deal, cutting him in on the Scragg loot, if he'd be nice and mind his own business. But Milo Marquand, alias Nicki Moretti, had worked too long alone to be willing to compromise now. Especially in view of the fact that the Scragg job would be the plum of his career.

"He can go to hell," the major muttered, "whoever he is!"

MRS. GEORGE SCRAGG was a mountain of a woman, with gray hair and thick bristle-gray eyebrows. Her skin was the same leathery tan as her husband's, and she seemed to be about the same age as her spouse. Much, to the major's joy, she seemed even more tremendously impressed than her husband had been.

"And you'll meet the duke, of course, the first chance you have to visit your newly acquired mines," the major said affably.

Mrs. Scragg beamed wrinkles of sheer heavenly joy.

"I've never met real royalty before," she said excitedly. Then to her spouse: "I think it's so fine of the major, don't you, George?"

And so it went for the rest of the dinner. The Scraggs were as putty in the major's deft hands. It was childishly simple. So childishly simple that it drove away the nettling irritation he had felt over the cable and cigarette hoaxes. When at last he brought the Scraggs up to his suite to "complete the transaction and cement our friendship," the major was glowing with triumphant good cheer.

He even made a point of offering George Scragg one of the personally inscribed Fielding-Nought cigarettes, and of fishing out of the waste basket and showing him, as a casual item of interest, the cable from the Maharajah.

It was ten o'clock when, with the certified check for two-hundred-thousand from George Scragg in his pocket, the major bid the couple good-night at his door.

"It has been charming," he smiled. Laughingly, he added: "You can stop that check the first thing in the morning, George, if the certified mine reports I show you aren't what I said they were."

Both Scraggs got a laugh out of this. The picture of a gentleman such as the major being a sharper was quite hilarious. They said their good-nights on a festive note.

The major bolted the door, once they'd gone, and drew forth the certified check with hands that trembled visibly. He felt like shouting wildly, or crying, or screaming. His elation was overpowering. And in the morning he'd have the fraudulent mine reports to turn over to George Scragg. He'd telephoned long-distance to Chicago and spoke cautiously to a trusted middle-broker who had assured him that he would make a nice set of reports which would arrive special delivery.

Major Milo Marquand sat himself down to a tumbler of whisky and a bottle of soda.

HE was just a bit woozy when the knock came on his door. It was repeated before he heard it. He crossed the room, after hiding the check under the desk blotter, and cautiously opened the door. It was a uniformed messenger who stood there.

"Major Marquand?" asked the uniformed boy. "A message from Chicago, special delivery."

The major smiled, signing for the envelope. His middle-broker had worked exceptionally fast. The reports were already here. He could show them to the Scraggs this very evening if he wished.

The boy left and the major returned to his desk. Minutes later he was poring somewhat foggily over the reports on the worthless South African dirt holes. And seconds after that he was jolted into sobriety by what he read.

"Mining holdings are valuable as hell," the report read. "Don't do a thing with them until you hear further from me. Came across the amazing news while looking up the correct forms in the consulate offices. This is on the level! Sit tight! Looks as if better than half a million is involved. Will demand my cut on this, if reports I found are true. Don't peddle the damned papers. I'm not kidding."

It was signed: "Schwartz."

Schwartz was the middle-broker in Chicago to whom the major had called. But at this minute he wasn't thinking of Schwartz. Instead, the major was thinking sickly of one paramount fact.

The Scraggs were in possession of the mining deeds. The transaction was completed. He, greedy ass that he'd been, had sold out half a million in mining property for a paltry pittance. Major Milo Marquand was driving himself slightly insane with this anguished realization.

And it was at this moment, while the major sat there, staring stupidly down at the floor, that his eye happened to hit and hold upon a picture in a newspaper that had been dropped there.

The picture was that of a sober young oriental. The caption above it read, "War Relief Head Is Suicide."

Irritated, the major kicked the paper with his foot so that the picture was no longer visible. Perhaps it was his agitation over the imminent loss of a quarter of a million dollars. Or perhaps it was a faint, thin voice of conscience crying in the back of his mind. Suddenly, at any rate, the major could hear Ying's voice from that early afternoon.

"And through the hours of this day, may the demons of hell follow the untruths from your foul tongue."

Inexplicably, a cold sweat broke out on the major's forehead. It was as if Ying's voice was audibly in the room with him, mocking him. He stood up.

"To hell with this," he muttered. "I'm not out those papers yet. They were saps enough to take 'em, and they'll be saps enough to give 'em back."

And then, in spite of himself, he heard Ying's voice in the back of his mind, speaking as it had that afternoon.

"May the Gods of Truth control your lies against you this day."

Truth and lies. Well this was one lie that turned to truth. He'd profi—Suddenly the major was stopped short by the glimmering of a wild, foolish idiotic idea. But then his face twisted in cynical disdain.

"I can't let this momentary mess get me down," he muttered. "I've got work to do, and I'll have to do it fast."

GEORGE SCRAGG was in his dressing-robe when the major pounded on the door of their suite. He was sleepy-eyed, and obviously startled at seeing the major.

"I must talk to you, old chap," the major greeted him. He had no trouble in making his voice sound agitated. Mr. Scragg nodded bewilderedly, pulling his robe about his paunch and directing his visitor to a chair.

The major shook his head.

"No, old boy, I prefer to stand if you don't mind." Nervously he lighted a cigarette.

George Scragg sat down perplexedly and waited for the major to explain his visit. The major gave an excellent imitation of honest-man-struggling-with-a guilty-conscience. He paced back and forth, puffing nervously on his cigarette.

"I can't do it, old fellow. I just can't," the major declared in mental anguish when he considered the silence tense enough.

George Scragg blinked his eyes.

"Do what?"

"Let you take those mining deeds," the major made himself blurt the words, like a man desperate and ashamed all at once.

"But the deal—" George Scragg began bewilderedly.

"The deal was a dirty, rotten, crooked mess!" The major managed to put tears into his voice now.

"Dirty? Rotten? Crook—" George Scragg faltered in confusion.

"Yes, I was going to make you and your wife the victims of the first wretched, stinking trick I've ever pulled in all my life!" The major sat down suddenly, burying his head in his hands.

"You mean," said George Scragg, shocked, "those deeds are no good?"

"They are utterly worthless. The property they lease has been diamond-dead for over ten years," the major said chokingly.

"But my money," George Scragg was instantly on his feet, indignant. "What did you do with that check?"

"I've brought it with me, you can have it back!" The major rose and handed the check to Scragg. "Now give me those deeds, man, and let me leave before this damnable shame kills me."

But George Scragg, though slow about many things, was not quite so slow once he was forewarned that he was dealing with a man who had sharped him once.

"If those papers are worthless," he said suspiciously, "why do you want them back. I can just tear them up."

The major felt suddenly uncomfortable. He had underestimated George Scragg a little too heavily. But he had to stick to his role.

"My conscience wouldn't let me do it, wouldn't permit me to go through with the swindle," he said despairingly, switching to the groundwork of his approach. "You people were too decent. I tell you, I swear by the living gods that this is the first dishonest thought I'd ever entertained in my life!" The major was no slouch as a ham. His performance was more than slightly convincing to Scragg.

"Ma will be sorry to hear this," George Scragg said.

"I've been more or less out of my head for the past month, old boy," the major said emotionally, plunging onward. "I've not been well. In fact, well, the doctor's given me no time at all left in life. I'm liable to go any instant; my heart."

This struck deep in George Scragg.

"Why, gosh, yes," he agreed, "that would be enough to make anybody a little crazy now and then. I know it would me. Say, I'm terribly sorry," he concluded lamely.

If Major Marquand felt that he was digging deep into the tears and gush, the look on his audience's face was enough to convince him that it had been worth while.

"So I was really a little bit out of my head, old man, when I pulled that dirty trick on you two. The minute I regained the slightest normalcy, I regretted it."

"I think I understand, Major," George Scragg said sympathetically. "I had an aunt once who used to go temporarily off the handle when she had a severe mental strain. Don't worry, I'll say nothing of this to the Missus."

Major Marquand took Scragg's hand.

"Thanks, George old boy. You don't know what this has meant in torment and suffering for me. Have you got those worthless deeds?"

This time George Scragg handed across the papers without further urging. The major felt like yelling in triumphant glee as his fists closed about the deeds.

At the door George Scragg said:

"I'm grateful to you, Major, for your honesty. And you don't have to worry none about me telling a soul about your spells. And if you'd like, the Missus and I'll keep you company any time that you feel you might be dy—that is, feel as if dea—I mean—" Scragg floundered around in confusion.

The major gripped his hand.

"I know what you mean, old boy. I appreciate it." He made his voice husky, and tried his best to look like a man who'd die at the drop of a pin. Then the major stepped down the hall and Scragg closed his door softly in the background.

Had Scragg seen Major Milo Marquand's face—wreathed in an exultantly avaricious grin—he would have scratched his thick head and wondered even further about his strange experiences with the cultured British ex-army officer.

BACK in his suite, Major Marquand closed and locked the door hurriedly, going immediately to his desk where he sat down and carefully examined the South African mining deeds. They were just the same as when he'd turned them over to the guileless Scraggs.

And now the major picked up the recently arrived special delivery message from his confidante Schwartz. It was a pleasure for him to sit down once more and go over it. He removed the note from the envelope.

MINE HOLDING REPORT FORGERIES TO ARRIVE TOMORROW. THERE WILL BE THE USUAL CHARGE FOR SERVICES. TWENTY-FIVE BUCKS PER DEED. GOOD LUCK AND GOOD HUNTING.—SCHWARTZ.

Major Marquand stared popeyed at the page.This was not the note Schwartz had originally written. It was totally different, quite completely in reverse to what he had stated then. Why, this note read as if the mines weren't worth a damn at all!

Quickly, the major began to riffle through his other papers. Six, seven times, he returned to the envelope, searching through its folds to find the original message from Schwartz. But there was no other message. Only this.

Marquand felt as if he were going mad.

A telephone call to Chicago got him Schwartz. Frantically, the major demanded to know about the mine, about the note.

"Are you crazy, Major?" Schwartz demanded. "There was only one note. That told you that the fees would be the same."

Marquand tried, almost screamingly, to explain to Schwartz what he meant. But the go-between finally cut him off.

"Go to bed and sleep through it. I've never known you to drink on the job before." Schwartz hung up on him.

And now, maddeningly, Ying's voice came back to Major Milo Marquand. And with it the incredibly insane suspicion he'd had momentarily a half-hour or so ago.

"May the Gods of Truth," he could hear Ying say, "control your lies against you this day."

And suddenly, for no reason that he was conscious of, the memory of the cable from the non-existent Maharajah returned to Major Marquand. And with it came the recollection of the cigarettes, inscribed for him, and which he hadn't ever ordered.

MAJOR MILO MARQUAND squeezed his hands so tightly that the nails bit into his flesh. His mind was an agony of torment.

"Damn!" Marquand said explosively, standing up from his desk. "It's ridiculous. It's preposterous. I refuse to believe it. That oriental hodgepodge!"

But there were the cable from the Indian potentate, the ultra-expensive cigarettes, and the first message from Schwartz. They all had one thing in common. They all followed a particular lie of Major Marquand.

The cablegram had made his lie about the Indian Maharajah a fact.

The cigarettes had turned his play for swank to cold truth.

Schwartz's first note had made true the lies about the mining holdings which he'd told to the Scraggs.

And now, as a sort of utterly staggering clincher, Major Milo Marquand realized one last fact. He had—knowing the mines to be valuable—rushed to Scragg and lied about their value, calling them worthless. Significantly, when he returned to his room, the mining deeds were worthless. His last lie had been made true!

Marquand threw his hands over his face, as if in an effort to shut out these conclusions, to drive away their maddening implications. But the pieces fitted far too well to be ignored. Ying had cursed him. Ying had cursed him so that the lies he told this day would be truths.

"May the Gods of Truth control your lies against you this day." The words came to Marquand again, in Ying's voice. But even as he fought them from his brain, he realized something else. The curse ended with: "this day."

Frantically, Marquand recalled the part in the rest of the curse. The part that said: "through the hours of this day." Now he was utterly convinced. The curse was for this day, for twenty-four hours. This day was not yet over. Marquand glanced swiftly at the clock on his desk. No, by God, this day wasn't through yet. It was but a quarter to midnight.

"There are fifteen minutes left to this day," Marquand said savagely to himself. "And in those fifteen minutes, Ying, I'll make a sucker of you and your oriental curse!"

"Lies," he went on. "My lies become truths, eh? Well what's to prevent me from getting down to the lobby and lying my damned head off. I can make those mines worth millions in fifteen minutes. All I need is someone to lie to." He was laughing now, shakily and a little wildly.

Major Milo Marquand's voice had been choked, and now he was breathing heavily through his nostrils, chest heaving. He started swiftly for the door of his suite. Started swiftly and stopped with sickening abruptness. A sudden, horrible wrenching tore his chest, his face going ghastly pale.

The major had his hand on his heart, slumping slightly forward, seeking the refuge of a chair. He felt an incredibly engulfing wave of weakness as he sank into the chair. He wanted to curse his luck as his eyes found the clock. But there was not enough strength left. He dared not move. The weakness was overpowering, the ache in his chest unbearable.

And as the major sat there helpless, in agony, his eyes fixed staringly on the clock that mocked him, he knew that Ying had gathered in all the aces. The major would never get downstairs before the day was over. The major would probably never get downstairs again.

Hideously, now, his own words were swimming before his pain-blurred eyes. The words that had been so glibly called upon to eucre Scragg out of the deeds.

"The doctor's given me no time at all left in life. I'm liable to go any instant; my heart."

Major Milo Marquand knew, as the weakness grew more and more engulfing, that Ying's curse had made that last lie of his, that final rotten falsehood, an inescapable fact. With his last remaining strength, Major Marquand held himself erect in his chair—contemplating the web that truth can weave.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.